Prosperity Watch (Issue 88, No. 4)

July 30, 2018

The designation of census tracts for the federal Opportunity Zone program reveals the deep inequality that exists among communities across North Carolina. The goal of Opportunity Zones Program —established in a provision in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Job Creation Act — is to drive private, long-term capital to distressed census tracts by providing investors tax breaks on capital gains. The nomination of eligible census tracts for Opportunity Zone status, completed by state leaders, highlights the historic — and continued — underinvestment in communities of color in the state. The inequities in economic prosperity also necessitate a need to track the effectiveness of the Opportunity Zone program, as well as the types of public and private investments that are needed to unlock the potential of all communities in North Carolina.

Out of the 2,145 census tracts in North Carolina, 1,433 met the eligibility criteria — a tract poverty rate of 20 percent or higher or a median family income lower than lower than 80 percent of the area median income (AMI) — to be nominated for Opportunity Zone status. In North Carolina, 252 tracts have been designated.

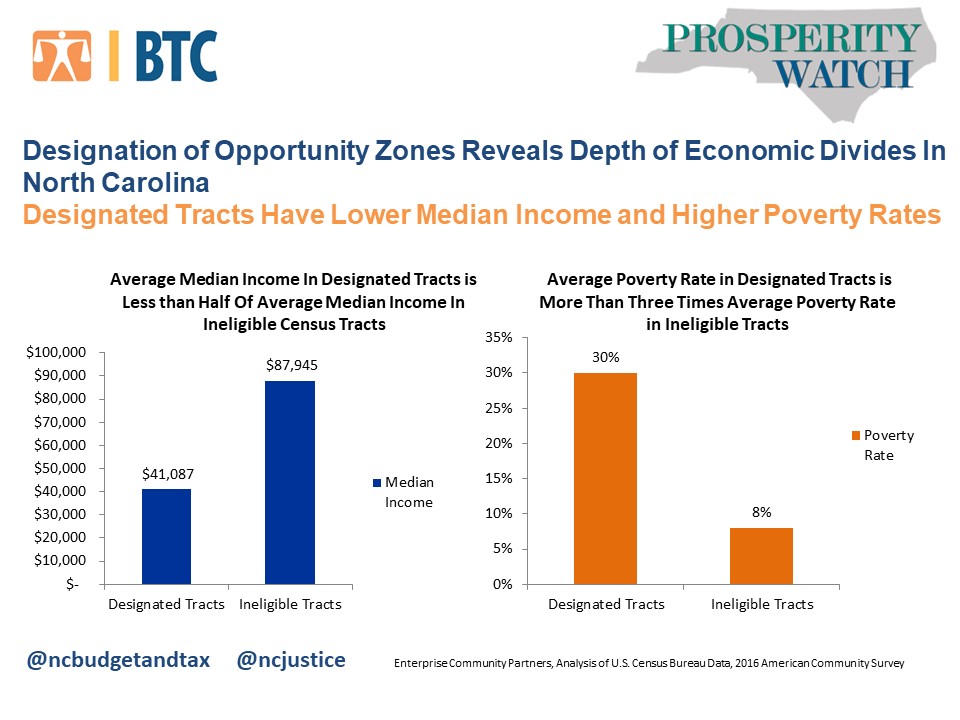

The poverty rate in designated zones is 30 percent, nearly 4 times the poverty rate of ineligible tracts, and the median income is $41,087 — less than half of the median income ($87,944) of ineligible tracts. These economic divides are also deeply rooted in barriers to opportunity, driven in major part by the lack of public and private investment in communities of color historically and to this day. The result is that eligible tracts have, on average, higher concentrations of people of color than tracts that were not eligible.

Data suggest that Opportunity Zones were designated in many census tracts where the need for enhanced investment is most acute. On average, designated Opportunity Zone tracts had higher levels of poverty and lower median incomes than tracts that were eligible but ultimately not designated. Designated opportunity zone tracts also had a higher percent people of color than eligible but not designated tracts, suggesting that dollars have the potential to drive capital to address a long-standing difference in the experience of investment across North Carolina communities. Designated tracts were also dispersed across the state, making it possible for communities facing a variety of challenges to benefit from the program.

Designation is the first step in driving Opportunity Zones toward more equitable outcomes, but it will likely not be sufficient to ensure the full potential of private capital is boosting the economic outcomes for all and directly benefiting current residents. The clear message of this data, however, is that an economic divide in North Carolina persists at a far more local level and in complex ways that require a focus on creating an inclusive economy that leads to economic prosperity for all residents in the state.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle