This session, General Assembly leaders have placed a massive expansion of the state’s voucher program at the top of their education agenda. Legislative leaders in both the House and the Senate want to triple the program’s size by opening it to wealthy families who have already enrolled their children in private schools. But new data shows that the existing program lacks adequate oversight and is potentially riven with fraud.

Data from the two agencies charged with overseeing private schools and North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarship voucher program show several cases where schools have received more vouchers than they have students. Several other private schools have received voucher payments from the state after they have ceased submitting enrollment data.

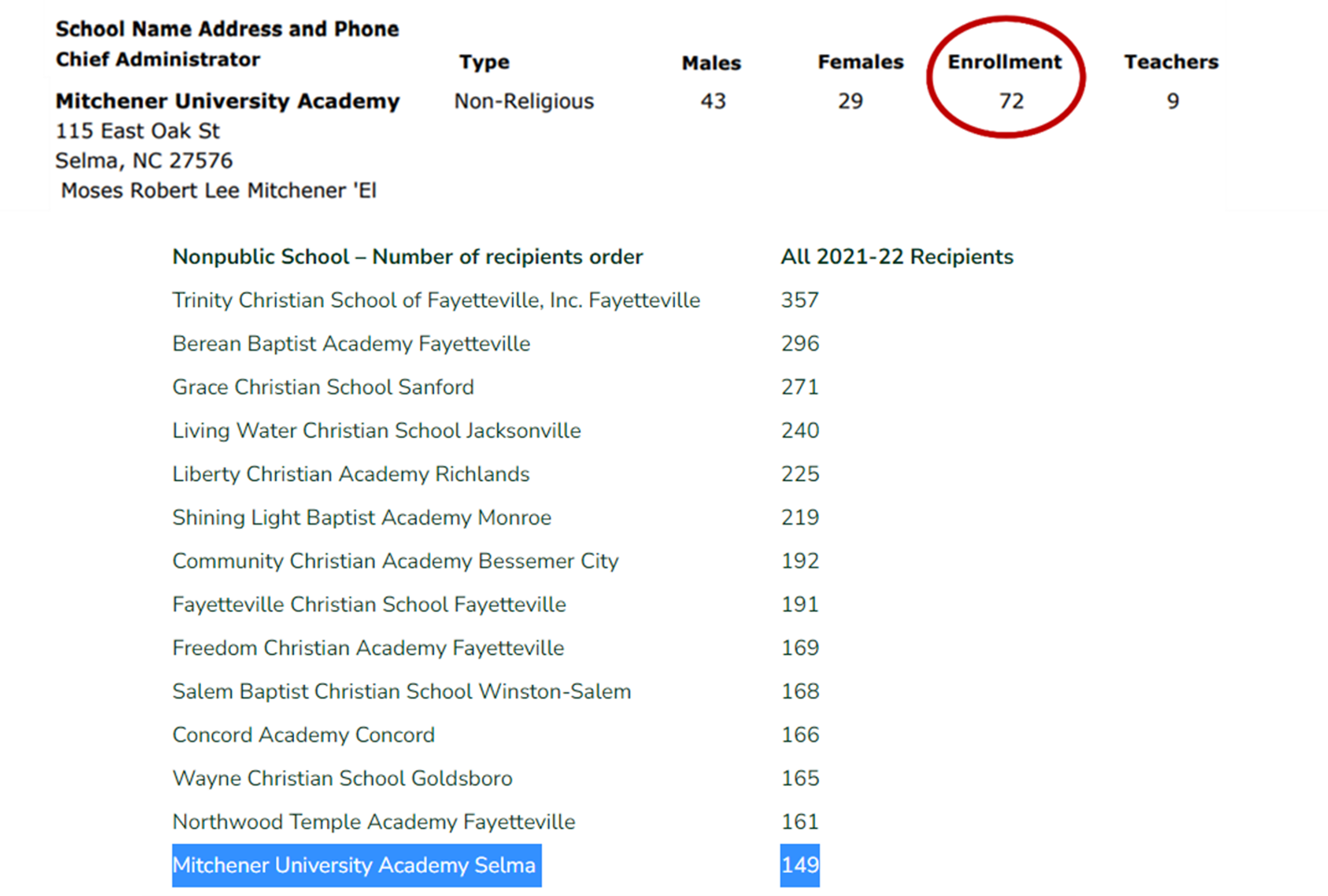

The Department of Administration’s Division of Non-Public Education (DNPE) compiles annual directories of active private schools. The North Carolina State Education Assistance Authority (SEAA) publishes data showing the number of voucher recipients at each private school.

An analysis of this data shows 43 times where a school received more vouchers than they had self-reported students.

For example, Mitchener University Academy in Johnston County reported a total enrollment of 72 students in 2022. That same year, the state sent them vouchers for 149 students. Based on this data, either every student received two vouchers, or the school pocketed about $230,000 of state money for students that never existed.

The data reveals at least 42 additional examples where private schools appear to have raked in more vouchers than they have students. If the enrollment figures are accurate, this represents approximately $1.6 million of fraudulent payments to these schools.

The actual number could be higher. Since 2015, 648 vouchers have been awarded to schools that failed to report their enrollment to DNPE.

In addition, 23 schools continued to receive vouchers after they stopped reporting to DNPE altogether. It’s unclear whether these schools were operating in the years they received vouchers. For example, Crossroads Christian School of Statesville submitted reports to DNPE from 2009 through 2019. They stopped reporting to DNPE in 2020. Yet that same year, the school received $57,300 for 15 voucher students, even though it’s unclear whether the school was operating for the entire school year.

These data discrepancies should represent a major red flag for lawmakers pushing voucher expansion. These discrepancies could represent innocent mistakes, or they could represent massive fraud. Unfortunately, lawmakers have failed to equip either DNPE or SEAA with the staff or authority to determine the reason for the discrepancies.

What is clear is that there is inadequate oversight of the Opportunity Scholarship voucher program. These issues will only get worse if lawmakers triple the program’s size. Lawmakers need to pause their expansion plans until they can figure out what’s going on.

Editor’s Note: More than three months after the publication of this post, DNPE provided the Justice Center with additional information pertaining to some of the schools that had more vouchers than reported enrollment. There were 18 times that these schools had submitted self-reported data to DNPE that was not reflected in the directories published on DNPE’s website. These schools’ enrollment data was not updated in DNPE’s directories because the schools had provided incomplete information to DNPE. DNPE’s system does not allow annual reports to be submitted if the school’s report is incomplete. Figures in this post have been updated as of October 9, 2023 to reflect the schools’ self-reported data in these pending submissions.

Kris Nordstrom is a Senior Policy Analyst with the Education & Law Project at the North Carolina Justice Center. Prior to starting work with the NC Justice Center in April 2016, Kris spent nine years with the North Carolina General Assembly’s nonpartisan Fiscal Research Division, where he provided budget analysis and information to all members of the General Assembly on public education issues. Kris holds a Master of Public Policy from the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University and a BA in Economics from Wake Forest University.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle