Eviction, and the displacement that follows, is a very harsh reality for many North Carolina residents. With ever increasing rent prices, the inadequacy of investment in affordable housing programs, compounded by the loss of affordable units because of expiring subsidies and stagnant wages, leaves many North Carolina families struggling to make rent payments. Indeed, nearly half of all renters in North Carolina are pay more than 30 percent of their incomes toward housing. Paying more than 30 percent of household income toward housing is considered unsustainable and means that families often have to choose between paying rent and paying utilities, adequate food, medicine, or other necessities. There is very little leeway if an unexpected emergency arises, like a broken down car or an illness. These factors place families at a greater risk of eviction.

As housing instability becomes a more pressing topic for housing advocates, it is increasingly important to understand the nature of evictions. This document gives an overview of statewide eviction trends, changes in evictions by county, and the social, economic, and health effects of evictions. The data presented represents the number of evictions that were filed. Even through not every eviction filed results in the tenant moving, all households that receive an eviction filing is at risk of eviction and displacement.

Eviction Trends

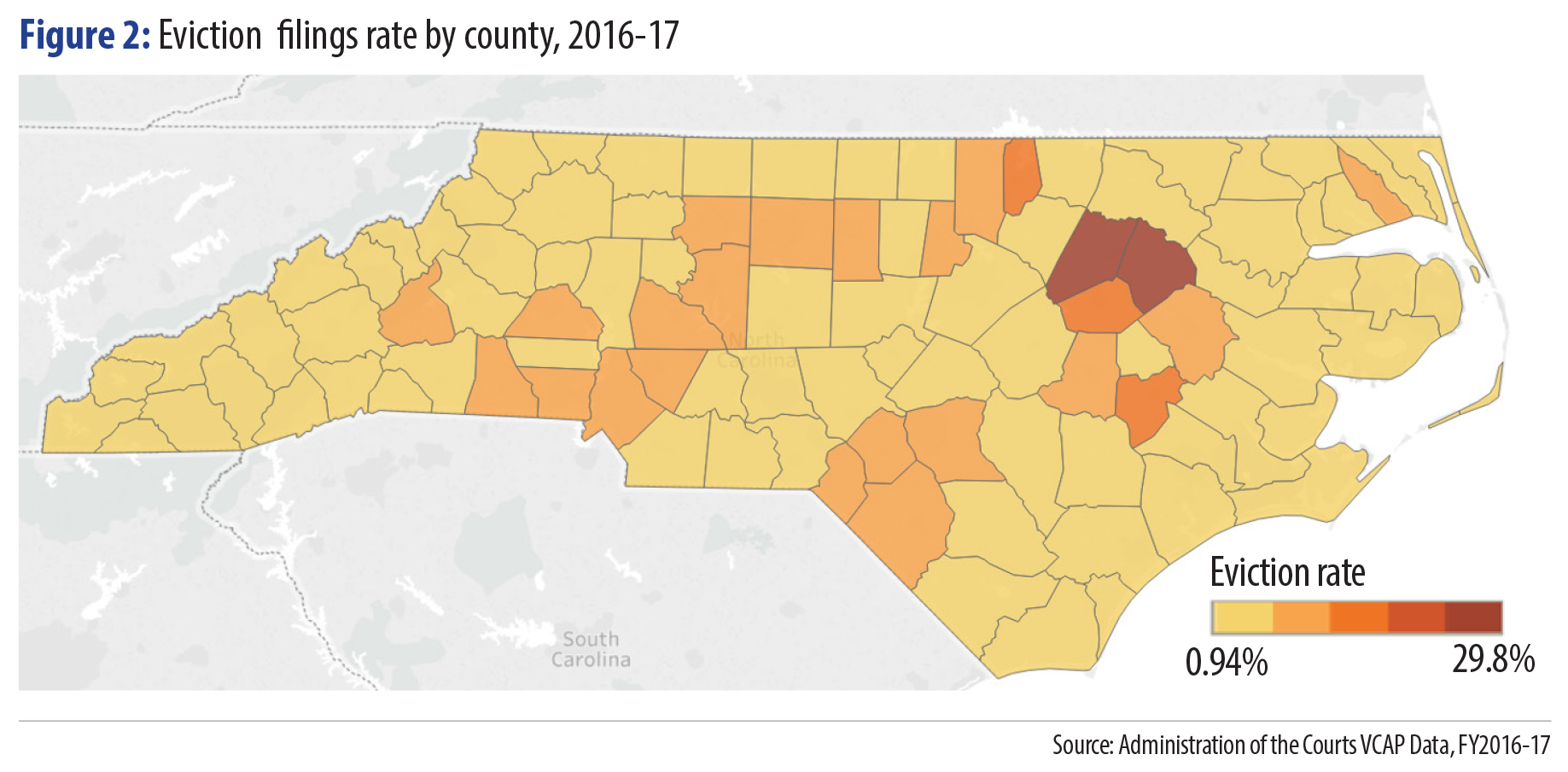

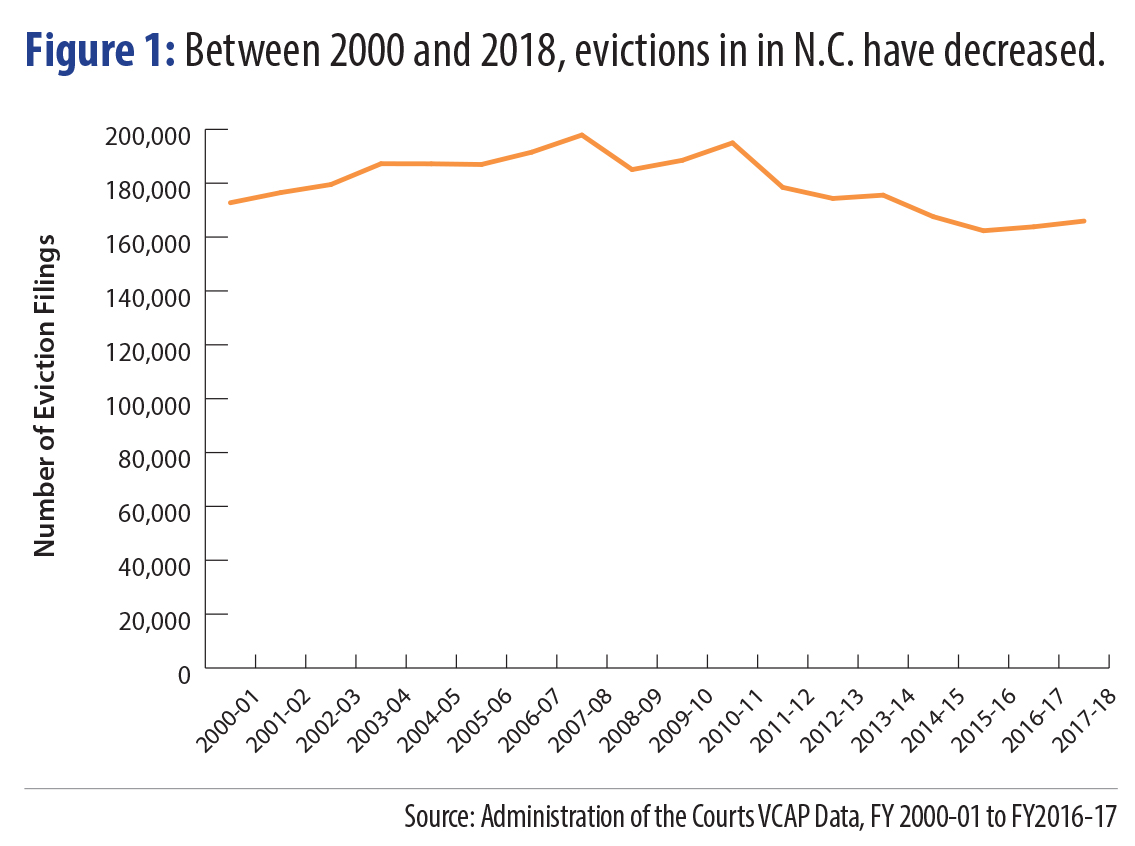

In fiscal year 2016-17, North Carolina had 163,818 eviction filings, a rate of 12.2 evictions per 100 renter households. There were 8,943 fewer eviction filings during fiscal year 2016-17 than during fiscal year 2000-01, a decrease of 5.17 percent (see Figure 1). However, the slight decrease does not make the issue of evictions and housing instability any less urgent. North Carolina, along with other states in the Southeast, still has some of the highest numbers of eviction filings in the county.

County Data

Counties across the state experience drastically different eviction filing rates, signaling that evictions are widespread and affect both urban and rural areas (see map). It is important to acknowledge these differences and understand that strategies to address evictions should be specific to the environment in a given area. For example, district court judges may be open to implementing an eviction diversion program, housing market nuances may allow for development of new affordable housing, and tenants’ rights organizations may be more active in some areas and non-existent in others.

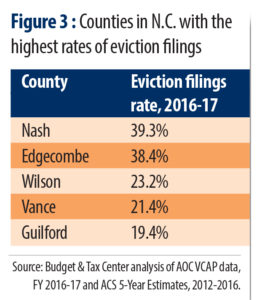

As of fiscal year 2016-17, the counties with the highest rates of eviction filings per 100 renter households are listed in Figure 3.

As of fiscal year 2016-17, the counties with the highest rates of eviction filings per 100 renter households are listed in Figure 3.

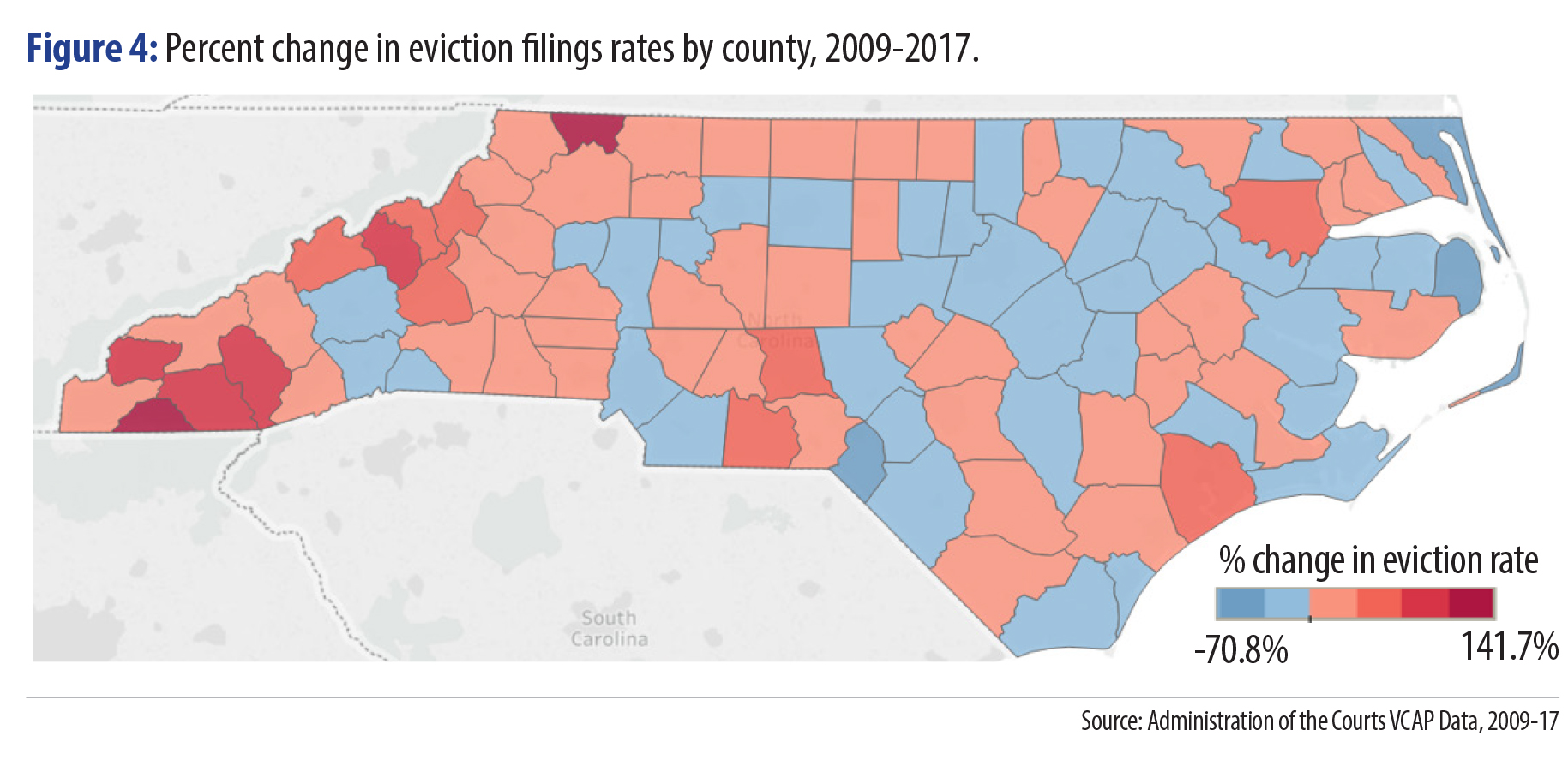

Changes in eviction filing rates over time also differ significantly across North Carolina counties (see map). Since fiscal year 2009-10, many counties in the western part of the state saw increases in eviction filing rates, yet still have some of the lowest eviction filing rates in the state. Adversely, counties with the highest rates of eviction filings as of fiscal year 2016-17 (Nash, Edgecombe, and Wilson) actually experienced a decrease in eviction filings since fiscal year 2009-10. This underscores the fact that even through North Carolina has seen a decrease in eviction filings, the impact on families and communities is still devastating.

Ripple effects of evictions on communities

Evictions have wide-ranging impacts on households and generate major costs for us all. When a family receives an eviction filing (even if the family is not evicted), it appears on the tenant’s permanent record and indicates to future landlords that the tenant has a poor rental history. Landlords can use this against prospective tenants to deny approval to a housing unit. Furthermore, receiving an eviction filing can make individuals and families ineligible for housing assistance programs. As a result, if they can find housing at all, families are relegated to living in substandard housing in undesirable areas.

Living in substandard housing conditions puts families at a higher risk of poor health due to increased exposure to contaminants such as dust, mold, lead, and structural deficiencies. These contaminants have lasting health effects, especially for young children. Evictions also negatively impact mental health, causing increased stress, anxiety, and depression. For children, evictions can lead to disruption to learning environment, stress and anxiety, as well as a greater threat to their physical well-being. Children who experience unstable housing conditions are more likely to use the emergency room for medical services, are under weight for their age, and are at a higher risk of developmental delays.

Evictions have significant social consequences as well. Stable communities often experience a strong sense of social capital, meaning that members of the community enjoy a network of trust and accountability. Building social capital takes time and when residents are forced to move due to an eviction, social capital in the community is disrupted. Children are often required to change schools in the middle of the school year and leave their friend groups behind.

The state of housing in North Carolina is unsustainable for many residents. Families are struggling to keep up with rent payments, face the threat of eviction, and settle for substandard housing. High rates of evictions are represented across the state, in both rural and urban counties. The lack of affordable housing in North Carolina places immense stress and pressure on cost-burdened households and negatively impacts physical and mental health in both adults and children. North Carolina families deserve housing that is safe and affordable, but as housing costs continue to climb, either wages or investment in affordable housing need to increase to match the demands of the housing market.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle