Prosperity Watch (Issue 71, No. 2)

March 13, 2017

North Carolina established a nationally-recognized early childhood system earlier than most states. The public and bipartisan support for investments to ensure that system prepares every child for academic success continues to grow. Central to ensuring the quality of early childhood education is an issue that does not often garner as much attention as the number of slots available to children in pre-K or the rate at which providers are reimbursed for care: the wages that early childhood educators are paid.

Evidence is clear that paying workers a living wage—and early childhood educators in particular—can improve job performance and strengthen connections to work and employers.

In North Carolina, as in the rest of the country, early childhood educators face significant barriers to make ends meet. Nationwide, child care workers earn just 39 cents for every dollar earned by workers in other occupations.[1] This is compounded by the higher likelihood that early childhood educators do not have access to health care benefits or retirement plans. Early childhood educators are more than 5.9 percentage points more likely to live in poverty than similarly situated workers in other occupations.[2]

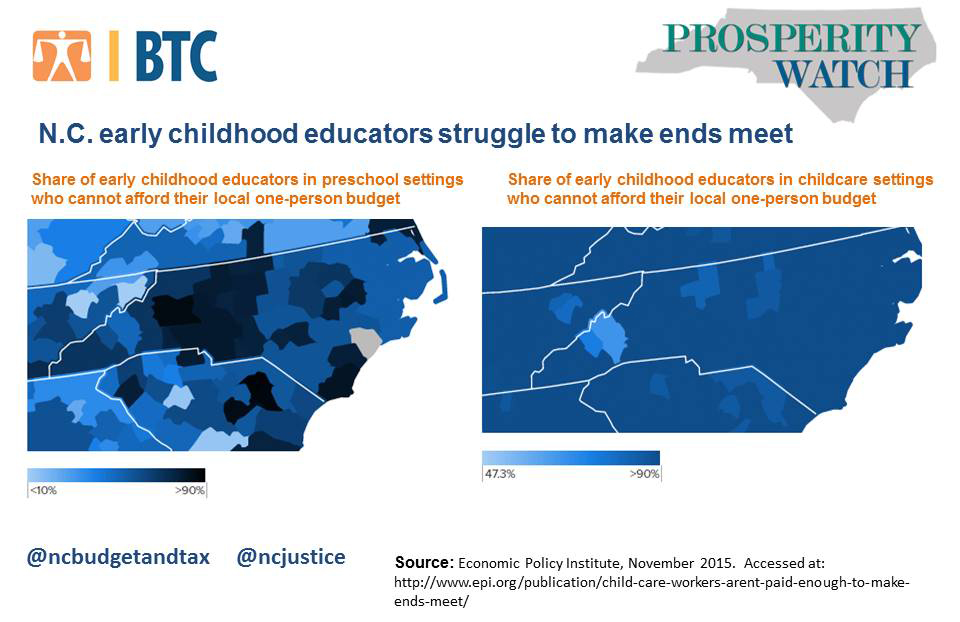

Analysis by the Economic Policy Institute shows that, in nearly all North Carolina counties, more than half of early childhood educators in either preschool or child care settings cannot afford the local cost of living on their hourly wage. The maps here demonstrate the percent of early childhood educators in preschool and child care settings by county who cannot make ends meet on their wages alone. In Buncombe and Henderson County, more than 65 percent of early educators in child care settings cannot afford local costs on their earnings. In Brunswick County, more than 80 percent of early educators cannot afford local costs on their earnings. The result of this failure of wages to keep up with costs of basic goods and services is that many workers will go without those basics or close the gap with support from family, charity and public programs.

Further compounding the goal of achieving a stronger early childhood foundation, early childhood programs remain out of reach for early childhood educators to send their own children based on analysis of median earnings. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ official affordability threshold for child care costs is 10 percent or less of a family’s income. In North Carolina, infant care represents 47 percent of a child care worker’s wages and 38 percent of a pre-school worker’s wages.

Early childhood educators’ wages are an important marker of how well North Carolina is doing in delivering high quality childcare.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle