Federal dollars and new revenue, combined with budget savings, create a responsible financing model through Medicaid Expansion

Medicaid expansion will not only provide much needed access to health insurance for at least half a million North Carolinians, but it is likely to also generate savings for the state budget. The federal dollars available to the state through Medicaid expansion will go far in addressing the costs associated with chronic conditions, medical debt, and health care costs that the state incurs as caregiver and employer to many. It will also make it possible for the state to redirect General Fund dollars then covered by these federal contributions to priorities that can further prevent a range of costs to the state and boost the economy as well.

Medicaid expansion can maximize federal funding available to North Carolina

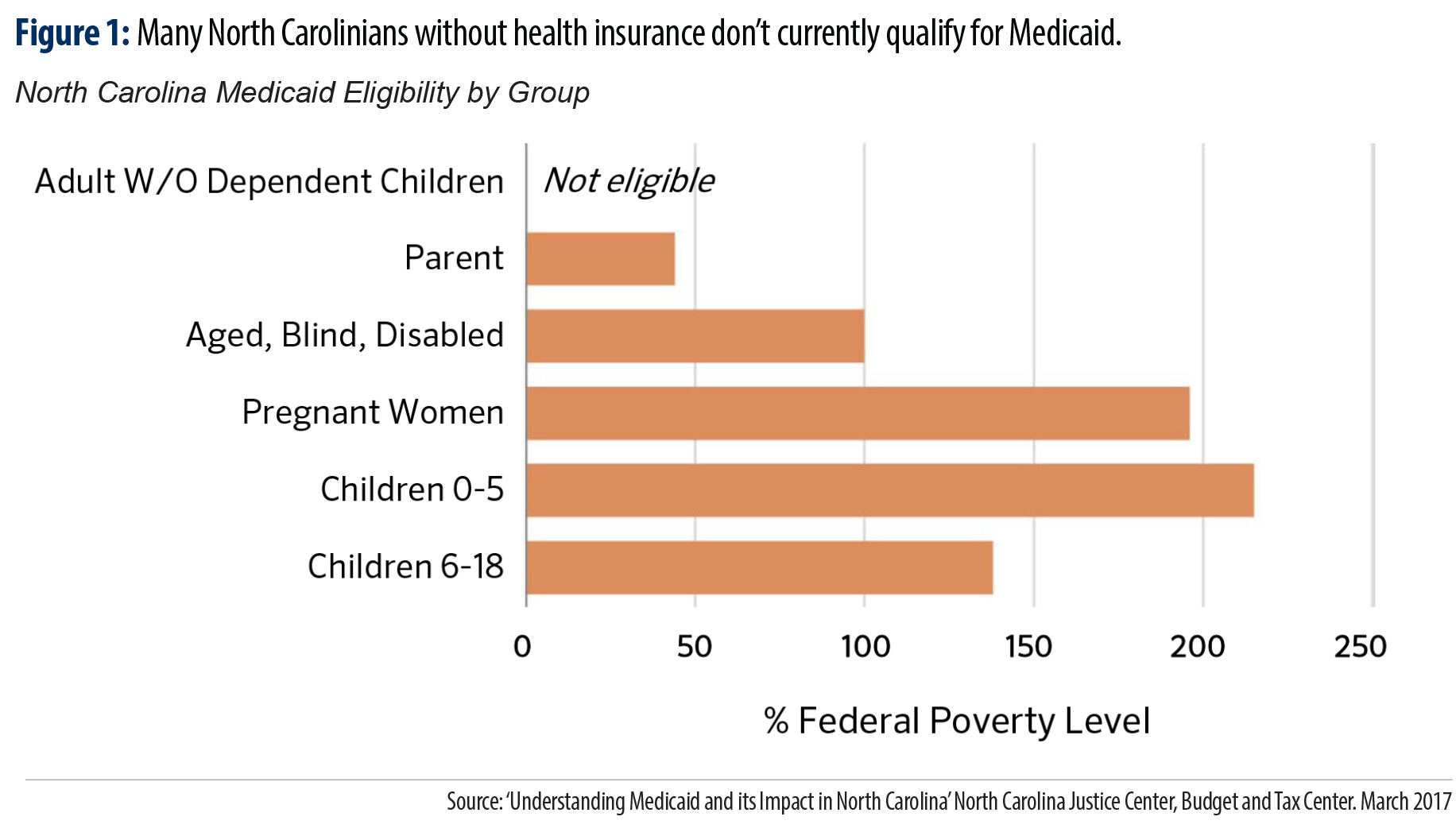

Currently, only certain categories of individuals are eligible for full Medicaid coverage in North Carolina. Childless adults in the state are ineligible at any income level while parents must have income of no more than 43 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) (Figure 1).[1] However under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), North Carolina is able to expand Medicaid for all those earning up to 138 percent FPL,[2] approximately $17,236 for a single household or $29,435 for a family of three.[3]

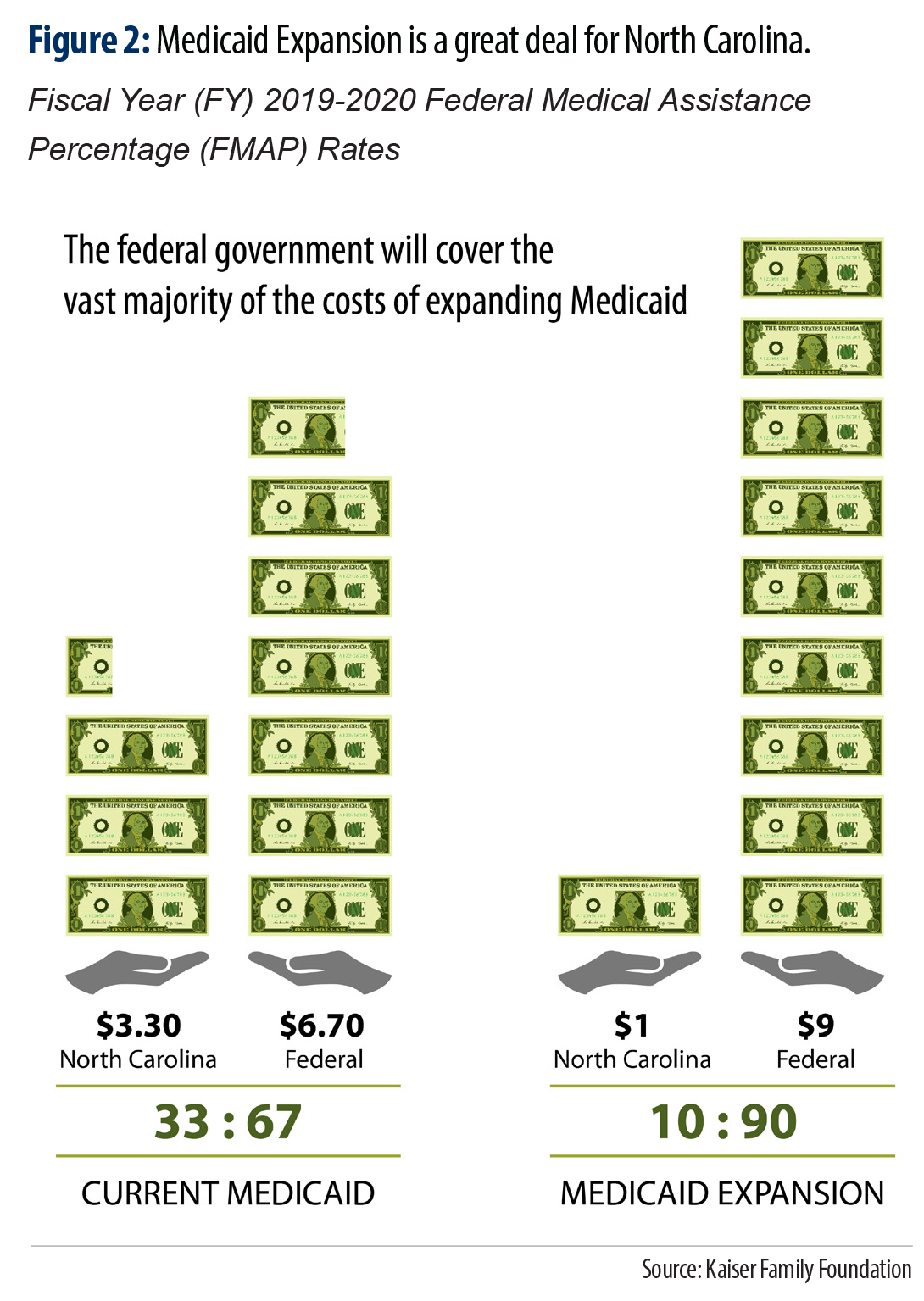

Currently, the federal government pays for 67 percent of North Carolina’s Medicaid costs. Under the terms of the ACA, the federal government will pay 90 percent of the costs of providing expansion coverage (Figure 2).[4]

Currently, the federal government pays for 67 percent of North Carolina’s Medicaid costs. Under the terms of the ACA, the federal government will pay 90 percent of the costs of providing expansion coverage (Figure 2).[4]

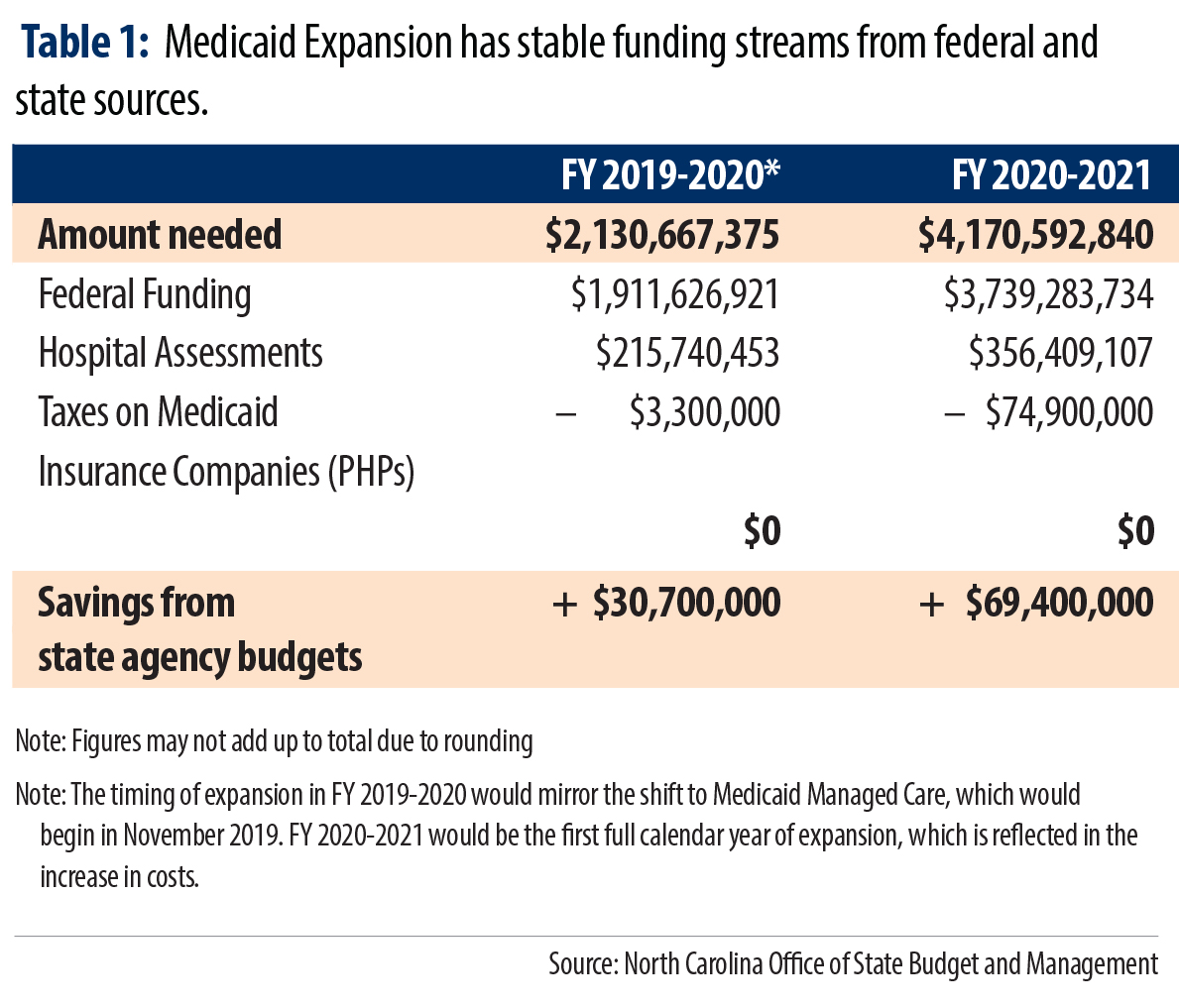

Data from the North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management show that the total cost of expanding Medicaid in North Carolina is $2.1 billion in FY 2020, rising to $4.2 billion in FY 2021 due to the full calendar year of expansion. These costs will be largely offset by the enhanced federal match. North Carolina would receive $1.9 billion in federal dollars for FY 2020 and $3.7 billion in federal dollars the following fiscal year.[5] The state share of the costs would be funded through a combination of hospital assessments and taxes levied on Prepaid Health Plans (PHPs). These data are summarized in Table 1 below. In addition, Medicaid expansion would lead to savings in several areas of the state budget, as detailed below under “Expanding Medicaid will produce significant savings to North Carolina’s budget”.

Providers in the Health Care Industry will contribute to financing the expansion through assessments

The Governor’s budget proposes collecting provider fees in order to partially finance the cost of Medicaid expansion. These dollars would generate $215 million in FY 2020 and $356 million in FY 2021. For the first several years of expansion it is expected that revenue from provider assessments will continue to increase as a function of increased enrollment for those newly eligible under expansion. In addition, the assessment rates may fluctuate to accommodate a growing Medicaid population.

Currently, providers at hospitals in nearly every state,[6],[7] including North Carolina,[8] are assessed fees in order to fund the state share of costs of Medicaid. States have relied on the contributions of providers to cover state Medicaid expansion costs in part or in full. In fact, many states are introducing new or increased assessment rates with the support of their state hospital associations, because the hospitals benefit by serving more people and receiving reimbursement for those services from Medicaid.[9] Thus, while the assessment rates may increase to accommodate a growing population receiving Medicaid services, this will not necessarily result in a net loss of revenue because hospitals will be compensated for a greater proportion of care they provide.

Provider assessments are governed by three primary guidelines in order to be able to apply them to the state share of Medicaid: they must be uniform, broad-based, and states cannot offset the cost to providers for paying the tax.[10] These provider assessments allow managed care organizations (MCOs), hospitals, nursing homes and other health care providers to continue to benefit from Medicaid reimbursements for services while further recognizing the broader benefits to the health care industry of having more people seek early and preventative health care.

North Carolina has collected assessments on hospital providers since 2011 to offset the state’s cost of Medicaid,[11] which amounted to $215 million in anticipated revenue for FY 2012.[12] North Carolina currently assesses nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities for those with intellectual disabilities, and hospitals, with only the assessment on nursing homes approaching the hold harmless cap of 6 percent of total net patient revenues as set out in federal law.[13] It remains to be seen how, if at all, the current administration proposes to modify current assessments made on hospital providers in order to generate enough additional revenue, in addition to traditional Medicaid, to meet the state’s share under expansion.

Pending current legislation, taxes on PHPs will cover the remaining cost of expansion

As a result of North Carolina’s move to Medicaid Managed Care, PHPs, or health insurance plans, will soon be contracted to manage the care of the state’s Medicaid population. The federal guidelines that apply to provider assessments, described above, also apply to taxes on MCOs, and at least eight other states collect fees on the premium payments.[14]

Currently the North Carolina General Assembly is considering legislation that would extend the existing 1.9 percent tax on insurance companies to apply to the capitation payments, also called premiums, issued to PHPs.[15] This tax on gross premiums would generate $78.2 billion over the next two years due to expansion, with additional funds resulting from capitation payments for the traditional Medicaid population.

Expanding Medicaid will produce significant savings to North Carolina’s budget

Medicaid expansion can produce $100 million of savings to North Carolina’s budget in the first two years it is in effect. These initial fiscal savings on health care costs are what can be considered first order effects and don’t capture the full cost savings that would come from a healthier population with greater financial security. Moreover, these cost savings are those estimated for taxpayers and don’t include the projected reduction in uncompensated care provided by hospitals which could be reduced by $56 million.[16]

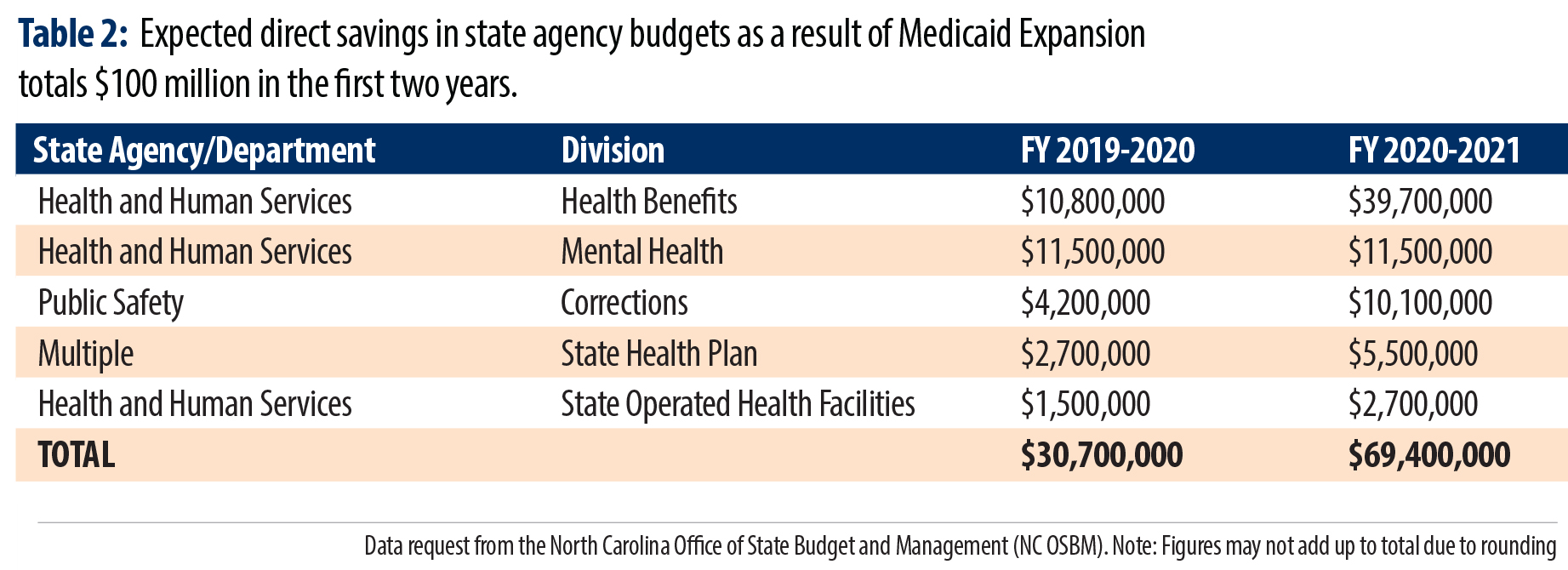

Medicaid expansion is likely to produce savings in five key areas of North Carolina’s budget, summarized in Table 2.

- Reimbursement at the higher federal match rate for those currently served through Medicaid would reduce state costs in the Division of Health Benefits. Additional cost savings for certain services currently covered under Medicaid that would qualify for a higher federal match. Specifically, services through the Family Planning program, Medically Needy program, Medicaid for pregnant women, and the Breast and Cervical Cancer Control program. These costs savings have been realized in a number of states.

- Fewer uncompensated behavioral health services would reduce costs in the Division of Mental Health. As a result of Medicaid expansion, mental health agencies will be able to seek reimbursement for more of the services they provide. This is because expansion would result in fewer uninsured patients. Without expansion, providing care to uninsured individuals is largely not reimbursed, which poses challenges for mental health and other health care facilities to remain open.

- Direct payment for health care services and treatment for those in the criminal justice system would be reduced via the Department of Corrections budget. Providing inpatient hospital services to individuals who are incarcerated, many of whom are currently categorically ineligible for Medicaid, will result in a great deal of savings for the state. The state is required to provide health care services for those in the justice system, however many of those individuals are uninsured while they are incarcerated. Medicaid expansion will provide a way for the state to be reimbursed for those services.

- Coverage of state employees whose income and family size meet the eligibility for Medicaid expansion would save State Health Plan funds. This is one mechanism by which the costs of delivering health care to state employees is most likely to be reduced through expansion. Some state employees have incomes that fall within the eligibility criteria and the state’s costs for providing a share of their care could be reduced should they enroll in Medicaid.

- Savings in the operation of North Carolina’s 14 state-operated health facilities, funded through the Division of State Operated Health Facilities. These facilities provide services to adults and children for mental illness, developmental disabilities, substance use disorders, and neuro-medical needs. Major areas of savings have been realized across the country in the areas of justice and public safety, mental health and substance use treatment, and can lead to significant savings in the long-term.

Medicaid expansion has produced budget savings in states across the country

Since North Carolina has lagged the nation in expanding Medicaid, insight into the scale of cost savings can be gained from the experience of the 33 states and the District of Columbia that have already provided health insurance coverage to more people.[17]

Numerous national studies of Medicaid expansion in states have documented state budget savings in a broad array of funding areas as well as no offsetting reductions in other areas of the budget—like education or transportation—so that the state match could be met.[18] Notably, a 50-state analysis of Medicaid spending found that there was not a statistically significant increase in state Medicaid spending in states that have expanded.[19] Moreover, net savings are projected to continue into the future. In Montana, Arkansas and Michigan as well as projections for Virginia find savings will continue over multiple years as the state reduces budget costs related to corrections and delivering substance use and mental health services.[20]

Two states similarly situated to North Carolina for their demographic and economic profile have documented significant cost savings covering the majority of the state match. In Ohio, nearly 70 percent of the state’s share is estimated to be offset by savings in the budget through “lower spending on corrections (since enrolling people in Medicaid after they’re released from jail or prison decreases recidivism) and increased revenue from assessments on the managed care plans that serve the expansion population”.[21] Louisiana documented cost savings of $199 million to the state through multiple factors that notably included a reduction to the state share as individuals were able to be covered at the higher federal match rate.[22]

Key to realizing the full fiscal benefit is covering all eligible North Carolinians.

To fully realize the cost savings for state taxpayers, North Carolina policymakers must design Medicaid expansion in a way that covers the maximum amount of those newly eligible for coverage. This means North Carolina should not erect costly barriers to coverage, such as excessive premiums and reporting requirements, which states like Arkansas and Kentucky have pursued.[23], [24] These costs are both direct to the state for the administration of reporting requirements and indirect in the form of coverage losses and in some cases employment losses due to losing health insurance.

Medicaid expansion offers North Carolina a more direct and cost-effective way to fund health care services. But ultimately, increasing the number of North Carolinians with health insurance and the benefits of affordable, consistent access to care is about boosting the well-being of families and communities. The broad benefits to our state will not only support the well-being of us all but will also generate savings in the state’s budget over time.

[1] Where are states today? Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children, pregnant women, and adults. (2018) Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/where-are-states-today-medicaid-and-chip/

[2] Garfield, R., Damico, A., & Orgera, K. (2018).The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Mediciaid. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/

[3] United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2019).Poverty guidelines. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines

[4] This FMAP rate is set in statute and is not set to expire.

[5] Data request from the North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management

[6] Health provider and industry state taxes and fees. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/health-provider-and-industry-state-taxes-and-fees.aspx

[7] Gifford, K., Ellis, E., Edwards, B.C., Lashbrook, A., Hinton, E., Antonisse, L., Valentine, A., & Rudowitz, R. (2017). Medicaid moving ahead in uncertain times: Results from a 50-state Medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2017 and 2018. Retrieved from http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Results-from-a-50-State-Medicaid-Budget-Survey-for-State-Fiscal-Years-2017-and-2018#page=51

[8] North Carolina Hospital Provider Assessment Act, NC Stat. §§ 108A-120-128.

[9] Health care provider assessments: A state-based funding solution for closing the coverage gap. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.communitycatalyst.org/resources/publications/document/ProviderAssessmentsforCTG_06.10.15.pdf

[10] States and Medicaid provider taxes or fees. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/states-and-medicaid-provider-taxes-or-fees/

[11] North Carolina Hospital Provider Assessment Act, NC Stat. §§ 108A-120-128.

[12] North Carolina General Assembly. (2011). Legislative fiscal note. Retrieved from https://www.ncleg.net/Sessions/2011/FiscalNotes/Senate/PDF/SFN0032v1.pdf

[13] States and Medicaid provider taxes or fees. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/states-and-medicaid-provider-taxes-or-fees/

[14] Smith, V. K., Gifford, K., Ellis, E., Edwards, B., Rudowitz, R., Hinton, E., Antonisse, L., & Valentine, A. (2016) Implementing coverage and payment initiatives: Results from a 50-state Medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2016 and 2017. Retrieved from http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Implementing-Coverage-and-Payment-Initiatives

[15] https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookUp/2019/H114

[16] Ku, L., Bruen, B., Steinmetz, E., & Bysshe, T. (2014). The economic and employment costs of not expanding Medicaid in North Carolina: A county-level analysis. Retrieved from https://www.conehealthfoundation.com/app/files/public/4202/The-Economic-and-Employment-Costs-of-Not-Expanding-Medicaid-in-North-Carolina.pdf

[17] Status of state Medicaid expansion decisions: interactive map. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/

[18] Antonisse, L., Garfield, R., Rudowitz, R., & Artiga, S. (2018). The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: Updated findings from a literature review. Retrieved from http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-The-Effects-of-Medicaid-Expansion-Under-the-ACA-Updated-Findings-from-a-Literature-Review

[19] Cross-Call, J. (2017). More evidence that Medicaid expansion hasn’t hurt state budgets. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/blog/more-evidence-that-medicaid-expansion-hasnt-hurt-state-budgets

[20] Cross-Call, J. (2018). Medicaid expansion continues to benefit state budgets, contrary to critics’ claims. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/health/medicaid-expansion-continues-to-benefit-state-budgets-contrary-to-critics-claims

[21] Cross-Call, J. (2018). More evidence that Medicaid expansion improves health, supports employment. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/blog/more-evidence-that-medicaid-expansion-improves-health-supports-employment

[22] Antonisse, L., Garfield, R., Rudowitz, R., & Artiga, S. (2018). The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: Updated findings from a literature review. Retrieved from http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-The-Effects-of-Medicaid-Expansion-Under-the-ACA-Updated-Findings-from-a-Literature-Review

[23] Wagner, J. (2019). Medicaid coverage losses mounting in Arkansas from work requirement. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaid-coverage-losses-mounting-in-arkansas-from-work-requirement

[24] Solomon, J. (2018). Kentucky Waiver will harm Medicaid beneficiaries. Retrieved rom https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/kentucky-waiver-will-harm-medicaid-beneficiaries

Justice Circle

Justice Circle