Limited incomes, minimal assets, and high costs of basic necessities limit the ability of low-income households to afford even small monthly coverage costs

As North Carolina decision-makers explore ways to expand Medicaid and close the state’s coverage gap, some have proposed requiring beneficiaries to pay a monthly premium in order to maintain their coverage. Given the economic realities facing those living without health care coverage, as well as other states’ failed experiments, it is clear that requiring premiums of Medicaid expansion enrollees would create major affordability barriers for North Carolinians who stand to gain health insurance coverage.

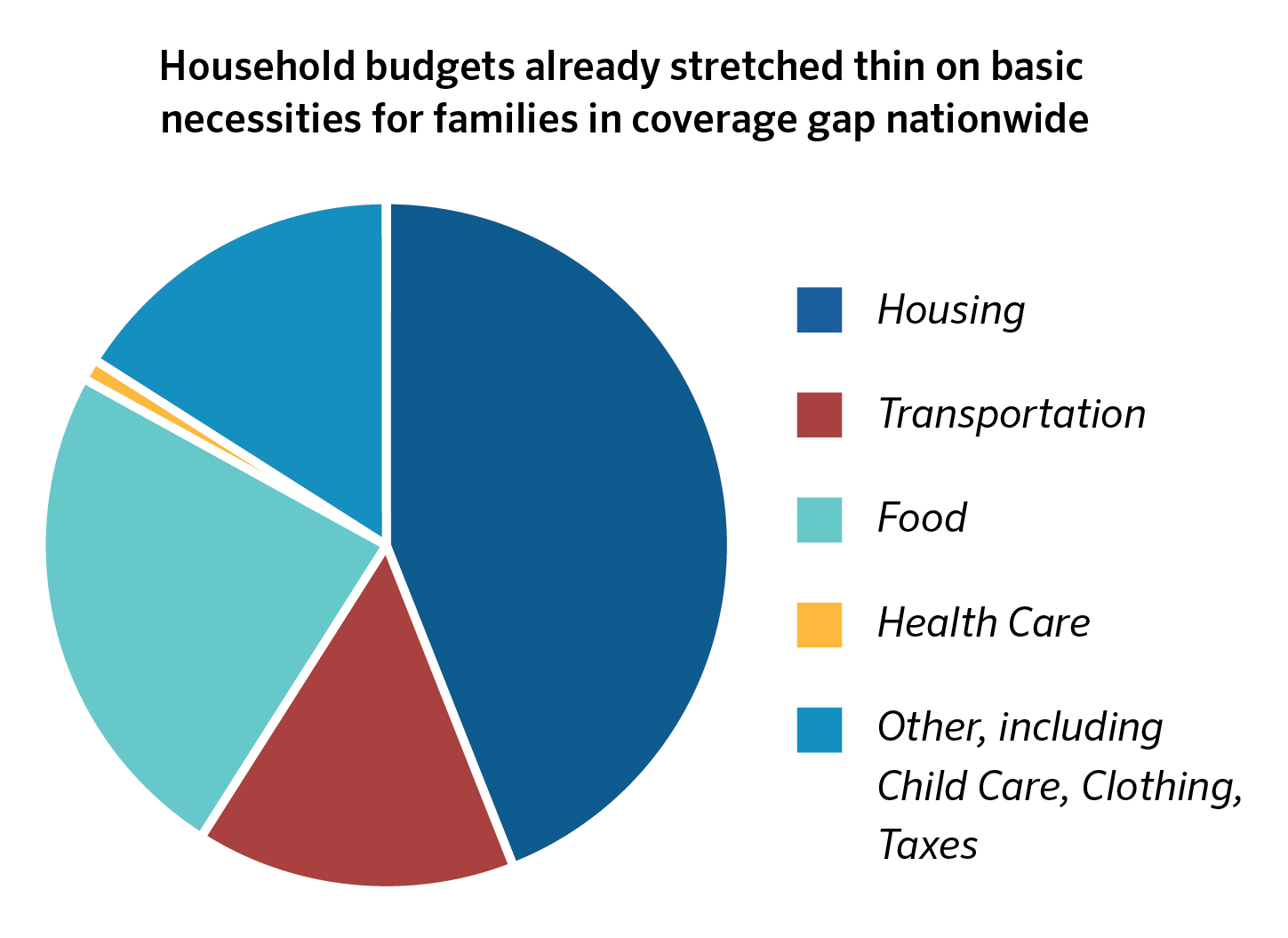

North Carolinians who would benefit from expansion earn incomes that are already insufficient to cover their monthly household budget costs for housing, food, child care, and other necessities, leaving little to nothing to pay for health care.

The evidence from other states is clear: premiums create barriers to health coverage and care for individuals with low incomes due to their inability to pay. When people lose Medicaid because of premium requirements, it reduces their ability to access health care and puts an even greater strain on already limited household budgets.

If lawmakers impose premium requirements on new Medicaid enrollees, a significant coverage gap will remain. People with low incomes will remain uninsured due to premium costs, leaving too many North Carolinians unnecessarily uninsured and unable to treat their health conditions.

Moreover, without full closure of the current coverage gap, the state won’t be able to draw down all available federal funds, nor will we realize full fiscal savings for agency budgets currently funding health care costs for uninsured North Carolinians. 1

North Carolinians in the coverage gap burdened by rising cost of living, low incomes

The North Carolinians who would gain eligibility under Medicaid expansion live in households that earn very low incomes. Under the state’s current eligibility rules, parents with incomes below roughly 43 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) are eligible for Medicaid.2 Adults without dependent children are ineligible for Medicaid no matter their income. This restrictive eligibility leaves those whose incomes are too low for private market subsidies in a coverage gap.3 Closing the coverage gap would extend Medicaid eligibility to all adults ages 19-64 with incomes up to 138 percent FPL.4 To translate this into dollars and cents, a parent with two children earning up to $29,440 a year would become eligible, as would a single adult earning up to $17,200 a year.5 Under today’s restricted eligibility system for full Medicaid coverage, that same parent in a family of three cannot qualify unless their income is under $8,004 a year,6 whereas the single adult cannot qualify no matter how low their income.

To charge premiums for Medicaid ignores the realities faced by households living in and near poverty. By definition, North Carolinians living in the coverage gap earn low incomes, and low-income households spend a far greater share of their earnings on the most fundamental necessities, such as housing, food, and utilities.7 The additional expense of Medicaid premiums would further limit their ability to make ends meet and would result in many foregoing coverage.

Data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey shows that, nationally, people living below 138 percent FPL and enrolled in Medicaid remain cost burdened without flexibility for major household expenditures like child care.

These data show that even with affordable health care coverage, incomes at this level cannot meet the needs of households striving to get by. Households pay on average 44 percent of their annual income in housing costs,8 well above the 30 percent standard for housing affordability.9 These high housing expenses, in addition to other basic needs, leave no budgetary room to meet child care payments, an increasingly significant portion of family budgets. This leaves households cost-burdened and unable to achieve a level of financial stability that can support economic mobility, child well-being, and greater participation in economic and community life.

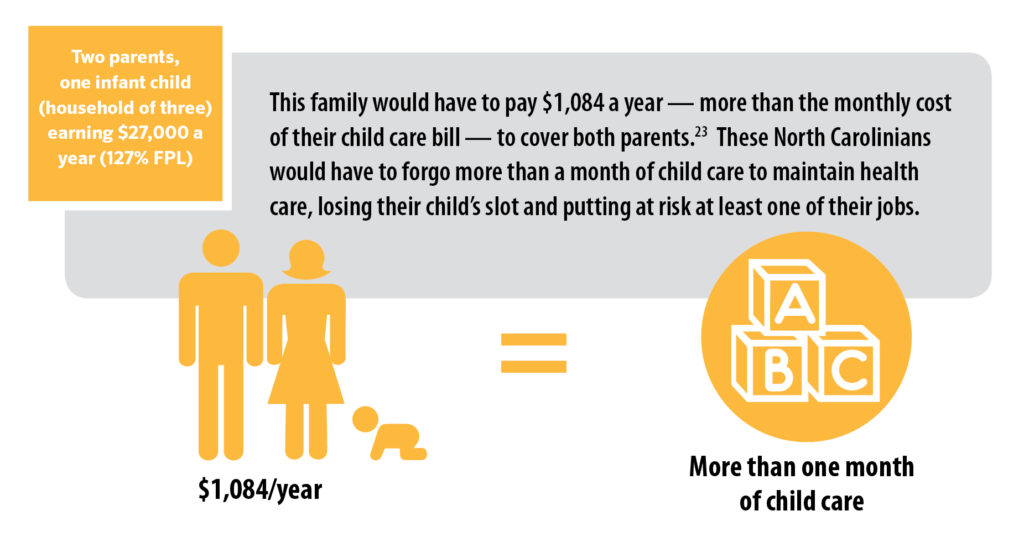

Recent data from Pew Charitable Trusts found that low-income households had a negative median annual income of $2,339 after accounting for expenditures.10 In other words, expenses exceeded earnings, leaving households to rely on credit, family and friends, or what little savings they may have to make ends meet. Given the low level of savings and high level of debt already held by households in North Carolina, these strategies are unsustainable in the long-run.11 In the short-run, cost burdens in housing, child care, and health have also been demonstrated to lead to ripple effects that push families further into poverty. A household unable to make rent may face eviction,12 or a family unable to pay for child care may lose their slot and need one worker to leave the labor force.13

In North Carolina, the data clearly show that low-income households are struggling to make ends meet. According to analysis by the North Carolina Budget & Tax Center, the average family of four needs to earn $52,946— well above the income eligibility threshold for Medicaid expansion — in order to afford the basic expenses of living in North Carolina.14 This is fully $17,411 more than the 138 percent threshold for a family of four that would be newly eligible under Medicaid expansion.

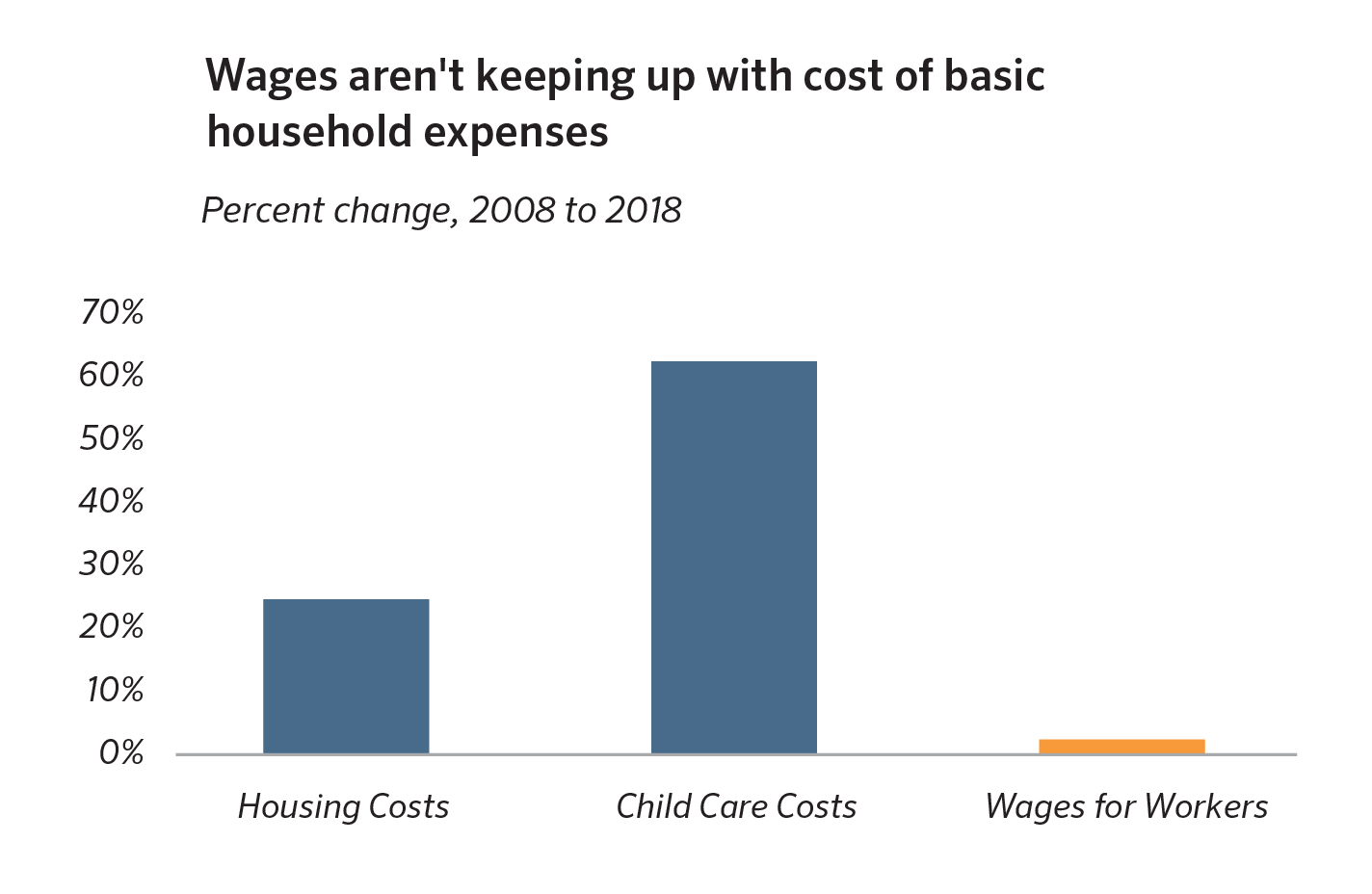

Unfortunately, making ends meet is not getting easier. This is primarily because the wages and

household incomes of North Carolinians remain slow to recover from the damage of the Great Recession and to keep up with the rising cost of the basics. Indeed, the wages for workers in the 30th percentile of the distribution, whose average annual income would be $27,000, have grown by just 2.4 percent since 2008, when adjusted for inflation.15 This is far below the growth in housing and child care costs, which is placing a squeeze on households attempting to keep a roof over their heads and remain engaged in the workforce.

Premiums in Medicaid would result in the persistence of a coverage gap in North Carolina

At the time of this brief’s publication, no proposal had been introduced in the North Carolina General Assembly’s 2019 legislative session to require premium payments by Medicaid expansion enrollees. However, in the 2017 legislative session, several lawmakers filed House Bill 662, called Carolina Cares. This bill sought to close the coverage gap for non-elderly adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty line,16 while imposing certain controversial requirements on enrollees, including conditioning eligibility on whether enrollees were “employed or engaged in activities

to promote employment.”17

Attracting perhaps less attention was a section that would require enrollees with incomes above 50 percent of the poverty line to “pay an annual premium, billed monthly, that is set at two percent (2%) of the participant’s household income.”18 Enrollees who miss premium payments after 60 days would lose their coverage and become uninsured unless they qualify for an exemption from the requirement. In order to re-enroll after having coverage taken away, a North Carolinian would have to pay “the amount in previously unpaid premiums owed.”

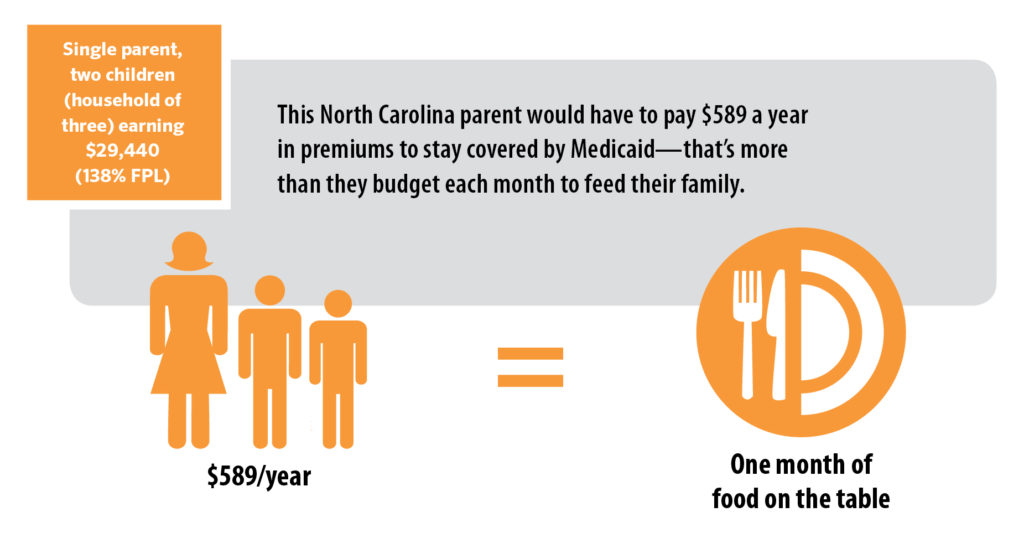

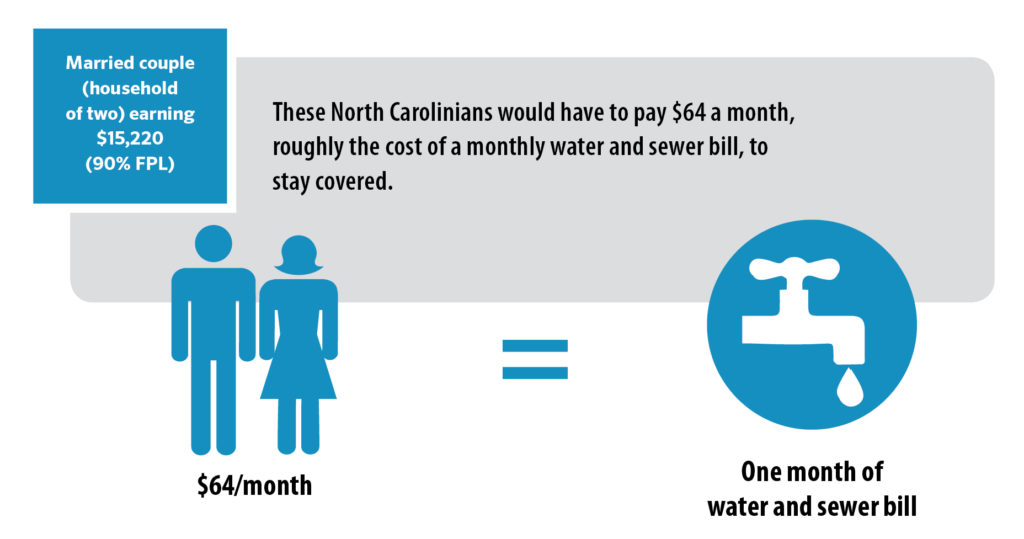

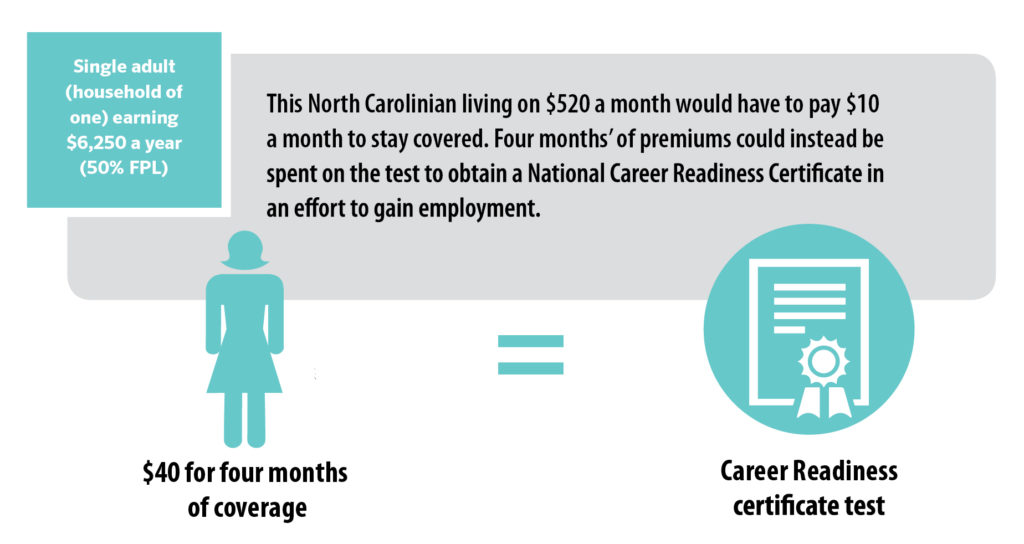

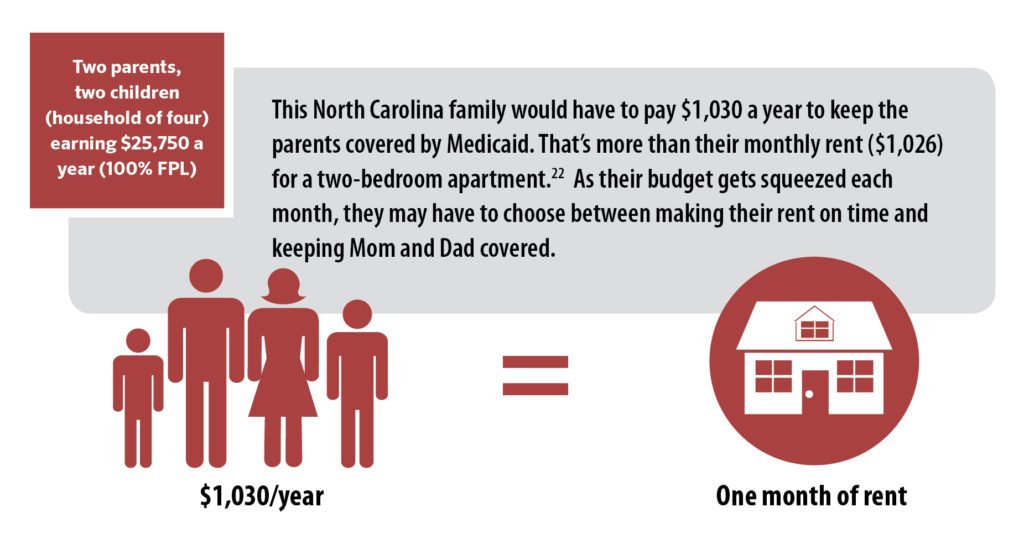

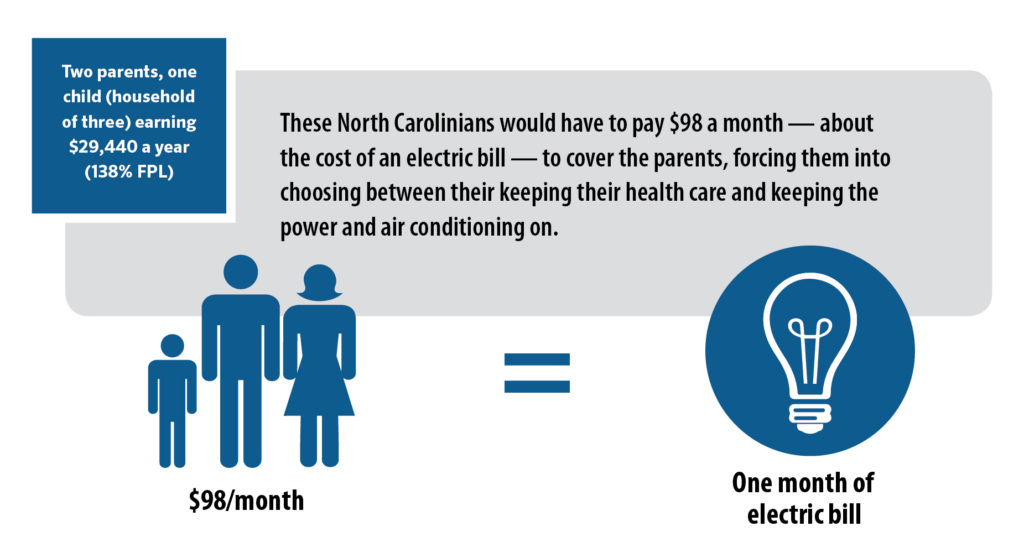

Outside observers have described premiums under Carolina Cares as “modest,”19 but the following household scenarios illustrate that a premium worth 2 percent of income can add up a lot, especially to low-income households with little-to-no income remaining after expenses on housing, transportation, food, and other basic necessities.

FIGURE 3: Premium Requirements for North Carolinians in the coverage gap would create an unnecessary barrier to health care

Evidence shows charging premiums to Medicaid enrollees with low incomes creates barriers to coverage and care

Generally, the Medicaid program does not permit states to charge premiums to enrollees with incomes below 150 percent FPL. Despite this, several states have sought permission from the federal government to waive these restrictions in order to experiment with charging premiums to Medicaid enrollees with much lower incomes.

To understand the effects of imposing premiums, participant contributions, and enrollment fees on Medicaid enrollees, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) conducted an extensive review of the research on such programs that took place in states between 2000 and 2017. Their synthesis of the research identified the following:

- Premiums create barriers to both obtaining and maintaining Medicaid coverage for individuals with low incomes. Creating or increasing premiums for enrollees in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) reduces coverage overall, leading to enrollees losing coverage and deterring eligible individuals from enrolling in the first place.

- Negative effects of premiums are more pronounced for households with lower incomes, especially those living below poverty. Among enrollees subject to premium requirements, those with lower incomes were more likely to become uninsured.

- After losing coverage due to premiums, uninsured individuals face barriers to financial security, experience obstacles to accessing care, and have more unmet health needs.20

While ample research supports the conclusions above, only a handful of states have experimented with premiums for Medicaid expansion enrollees (adults ages 19-64 with incomes below 138 percent FPL). Across those states, large swaths of enrollees are missing payments.

Michigan charges beneficiaries with incomes above the poverty line a monthly premium equal to 2 percent of income after they have been enrolled for six months,21 but only 38 percent of enrollees who owed premiums had paid them.22 In Indiana, where enrollees must make monthly contributions to enrollee accounts modeled after health savings accounts, 55 percent of all eligible enrollees missed premium payments.23 In Montana, fewer than half of enrollees with incomes below poverty paid premiums in June 2017, while payment rates among enrollees above the poverty line — for whom Montana may terminate coverage if they do not pay — were only 54 percent.24

The consequences for missing payments can be severe. In Indiana, if enrollees with incomes above poverty miss payments after a 60 day period, the state terminates their coverage entirely and locks out from re-enrolling for six months even if they remain income-eligible for the program.25 Of all Hoosiers whose coverage eligibility depended on paying premiums, 29 percent — nearly 60,000 people — lost coverage or were denied outright because they missed premium payments.26 For those below the poverty level who miss payments, Indiana moves them into less comprehensive coverage with copayments.27

Unsurprisingly, affordability was a key barrier for nearly half of Hoosiers who missed a payment after enrolling and for over a fifth of those who never made their first payment to start their coverage.28 However, affordability issues aren’t the only obstacles that premiums create for individuals with low incomes. Two-thirds of Indiana enrollees who missed payments attributed their problems to administrative issues, confusion about the process, or misunderstanding of their plan requirements.29

The Carolina Cares proposal shares a number of similarities, including the 2 percent required contribution and 60 day grace period, with the Indiana program. However, the premium requirements in Carolina Cares could lead to even greater shares of enrollees losing coverage in North Carolina than those in Indiana.

Unlike under Indiana’s program, enrollees with incomes below poverty could lose coverage entirely under Carolina Cares if they miss premiums. Nearly 60,000 Hoosiers with incomes above poverty were denied coverage after missing premium payments, but the 37 percent of Indiana enrollees below poverty who missed premiums were not terminated — they are instead given coverage that covers fewer services and with higher co-payments.30 Similarly situated North Carolinians would lose coverage under the Carolina Cares proposal. No single other state has gained federal approval to take Medicaid coverage away from enrollees with incomes below poverty for not making premium payments.

Previous research has shown that even seemingly small, nominal premiums can lead to disenrollment. In Wisconsin, a monthly premium of only $10 for adult Medicaid enrollees with incomes above 150 percent of poverty and children above 200 percent made enrollees 12 percent less likely to stay covered.31 Researchers believe this suggests that “the premium requirement itself, more than the specific dollar amount, discourages enrollment.”32

All in all, the evidence is clear: premiums create barriers — both administrative and financial — to health coverage and care for individuals with low incomes. When enrollees lose Medicaid because of premium requirements, it reduces their ability to access health care and puts an even greater strain on already limited household budgets.

Conclusion

Medicaid expansion provides North Carolina with a tremendous opportunity to draw down billions of new federal dollars and provide health coverage to hundreds of thousands of uninsured people. Given the 90 percent federal match on Medicaid expansion enrollees, our state would benefit from maximizing enrollment. The more people enroll, the more federal dollars come into the state, in turn generating economic activity, creating jobs, and producing fiscal savings for the state budget.

Any proposal that erects barriers to enrollment would limit these benefits. Ample evidence from other states makes clear that requiring premiums would create administrative hurdles and affordability challenges for North Carolinians with low incomes in need of health coverage. Instead of charging unaffordable premiums that unnecessarily take coverage away from people in need, lawmakers should design a proposal that will maximize federal funding to cover the most North Carolinians eligible.

At the end of the day, our state will not fully close the coverage gap if lawmakers charge premiums to North Carolinians who become eligible for Medicaid expansion.

Footnotes

- Khatchuturyan, S. Financing Health Care, BTC Report: NC Justice Center, Raleigh, NC. March 2019.

- Parent eligibility for Medicaid in North Carolina is tied to dollar thresholds, not to the federal poverty level, so 43 percent is an approximation. Source: Kaiser Family Foundation. Where Are States Today? Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility Levels for Children, Pregnant Women, and Adults. March 28, 2018. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/factsheet/where-are-states-today-medicaid-and-chip/

- Medicaid income eligibility limits for adults as a percent of the federal poverty level. (2018). Retrieved from https:// www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-adults-as-a-percent-of-the-federal-poverty-level/

- While Medicaid expansion eligibility is set at 133 percent of the federal poverty level, the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) calculation of income for determining eligibility includes a disregard equal to five percentage point deduction, effectively extending eligibility up to 138 percent of poverty in practical terms. For more, see ACA Note: When 133 Equals 138 – FPL Calculations in the Affordable Care Act. SHADAC. January 11, 2012. https:// www.shadac.org/news/aca-note-when-133-equals-138- fpl-calculations-affordable-care-act

- Calculations based on ASPE list of poverty guidelines for 2019. (Figures in text rounded from $17,236.20 for a household of one and $29,435.40 for a household of three). Source: HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2019. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://aspe. hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines

- Basic Medicaid Eligibility Revised April 1, 2019 [sic]. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. https://files.nc.gov/ncdma/documents/files/Basic- Medicaid-Eligibility-Chart-2019.pdf. Accessed via NC Department of Health and Human Services, NC Medicaid, Division of Health Benefits, “Medicaid Income Limits” under “Associated Files,” https://medicaid.ncdhhs.gov/medicaid/ get-started/eligibility-for-medicaid-or-health-choice/ health-choice-income-and-resources-requirements/ medicaid-income-limits on March 16, 2019

- Financial Condition and Health Care Burdens of People in Deep Poverty. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. July 16, 2015. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/ financial-condition-and-health-care-burdens-people-deep-poverty

- Majerol, M., Tolbert, J., & Damico, A. (2016). Health care spending among low-income households with and without Medicaid. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/ issue-brief/health-care-spending-among-low-income-households-with-and-without-medicaid/

- Affordable Housing. (n.d.) Retrieved from https:// www.hud.gov/program_offices/comm_planning/ affordablehousing/

- Note: Data correspond to households in the 25th percentile for income. Pew Charitable Trusts. Household Expenditures and Income. March 2016. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/ media/assets/2016/03/household_expenditures_and_in¬come.pdf

- Prosperity Now, 2019. Assets & Opportunity Scorecard for North Carolina, accessed at: https://scorecard. prosperitynow.org/data-by-location#state/nc

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2018, The effects of rent burden on low income families. Accessed at: https://www. bls.gov/opub/mlr/2018/beyond-bls/the-effects-of-the-rent-burden-on-low-income-families.htm and Desmond, Matthew, 2016. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City.

- Baldiga M, Joshi P, Hardy E & Acevedo-Garcia DChild Care is unaffordable for those who most need it. NIEER. . February 2019. Accessed at: https://nieer.org/2019/02/15/child-care-is-unaffordable-for-working-parents-who-need-it-most; DHHS, The effects of child care subsidy payments on maternal labor force participation. Accessed at: https:// aspe.hhs.gov/effects-child-care-subsidies-maternal-labor-force-participation-united-states

- Kennedy B. The Living Income Standard 2018. NC Justice Center: Raleigh NC. 2019. https://www.ncjustice.org/ publications/the-2019-living-income-standard-for-100- counties/

- Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

- While Medicaid expansion eligibility is set at 133 percent of the federal poverty level, the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) calculation of income for determining eligibility includes a disregard equal to five percentage point deduction, effectively extending eligibility up to 138 percent of poverty in practical terms. For more, see ACA Note: When 133 Equals 138 – FPL Calculations in the Affordable Care Act. SHADAC. January 11, 2012. https:// www.shadac.org/news/aca-note-when-133-equals-138- fpl-calculations-affordable-care-act

- House Bill 662 (2017-2018). https://www.ncleg.gov/ BillLookup/2017/H662

- House Bill 662 (2017-2018). https://www.ncleg.gov/ BillLookup/2017/H662

- Journal Editorial Board. Our view: ‘Carolina Cares’ shouldn’t be partisan. Winston-Salem Journal. November 26, 2018. https://www.journalnow.com/opinion/editorials/ our-view-carolina-cares-shouldn-t-be-partisan/ article_5005f619-9385-50c6-8ba7-52e2266fd799.html

- Artiga S, Ubri P, and Zur J.The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 1, 2017. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/

- Bradley K, Colby M, Byrd V, and Maurer K. Paying For Medicaid Coverage: An Overview of Monthly Payments in Section 1115 Demonstrations. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. September 21, 2017. https://www. medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/downloads/ evaluation-reports/paying-for-medicaid-coverage.pdf

- Musumeci MB, Rudowitz R, Ubri P & Hinton E. An Early Look at Medicaid Expansion Waiver Implementation in Michigan and Indiana. Kaiser Family Foundation. January 31, 2017. https://www.kff.org/report-section/an-early-look-at-medicaid-expansion-waiver-implementation-in-michigan-and-indiana-key-findings/

- Artiga S, Ubri P, and Zur J.The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 1, 2017. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/

- Coughlin TA, Burton R, Hill I, Fass J, and Marks J. Federal Evaluation: Montana Health and Economic Livelihood Partnership Plan A Look at the Program a Year and a Half into Implementation. The Urban Institute, prepared for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, State Demonstrations Group, Division of Demonstration Monitoring and Evaluation. December 14, 2018. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/ section-1115-demo/downloads/evaluation-reports/mt-help-focus-group-site-visit-rpt.pdf

- Bradley K, Colby M, Byrd V, and Maurer K. Paying For Medicaid Coverage: An Overview of Monthly Payments in Section 1115 Demonstrations. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. September 21, 2017. https://www. medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/downloads/ evaluation-reports/paying-for-medicaid-coverage.pdf

- Healthy Indiana Plan 2.0: POWER Account Contribution Assessment. The Lewin Group, prepared for Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA). March 31, 2017. https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program- Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/in/ Healthy-Indiana-Plan-2/in-healthy-indiana-plan-support- 20-POWER-acct-cont-assesmnt-03312017.pdf

- Bradley K, Colby M, Byrd V, and Maurer K. Paying For Medicaid Coverage: An Overview of Monthly Payments in Section 1115 Demonstrations. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. September 21, 2017. https://www. medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/downloads/ evaluation-reports/paying-for-medicaid-coverage.pdf

- Artiga S, Ubri P, and Zur J.The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 1, 2017. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/

- Healthy Indiana Plan 2.0: POWER Account Contribution Assessment. The Lewin Group, prepared for Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA). March 31, 2017. https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program- Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/in/ Healthy-Indiana-Plan-2/in-healthy-indiana-plan-support- 20-POWER-acct-cont-assesmnt-03312017.pdf

- 37 percent of enrollees under poverty had been moved to less generous coverage as of October 2016. Artiga S, Ubri P, and Zur J. The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 1, 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Tables-The-Effects-of- Premiums-and-Cost-Sharing-on-Low-Income-Populations

- Katch H. Restrictive Medicaid Policies Will Impede Innovation to Improve Care and Reduce Costs. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. March 14, 2019. https://www. cbpp.org/research/health/restrictive-medicaid-policies-will-impede-innovation-to-improve-care-and-reduce

- Artiga S, Ubri P, and Zur J.The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 1, 2017. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/

Justice Circle

Justice Circle