The public health and economic crises resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have impacted everyone. But while the virus itself does not discriminate, it has had a disproportionately negative impact on low-income communities of color, including many immigrant communities across North Carolina, because of policies that long have posed and continue to pose barriers to well-being. These crises have highlighted large gaps in our systems and policies that have existed for decades and systematically have left out large swaths of our population who are critical to the fabric and functioning of our communities.

The exclusion of immigrants from state and federal government’s actions prior to and in response to these two crises puts North Carolina at a disadvantage as communities work to manage and overcome the crises. These challenging times have demonstrated clearly that the well-being of each of us is tied to all of us. When one large segment is disadvantaged, it is in the interest of all to ensure that everyone can receive the resources and supports they need — not only to survive but to thrive.

Immigrants are vital workers in our communities

Immigrants perform a large share of the frontline work that helps keep communities functioning during this pandemic. That frontline work includes jobs in health care; child care and social services; grocery stores, convenience stores, and drugstores; public transit; building cleaning services; and trucking, warehouse, and postal services. Data from before the pandemic show that nearly 8 percent of North Carolina’s workers in frontline industries are foreign-born.[1]

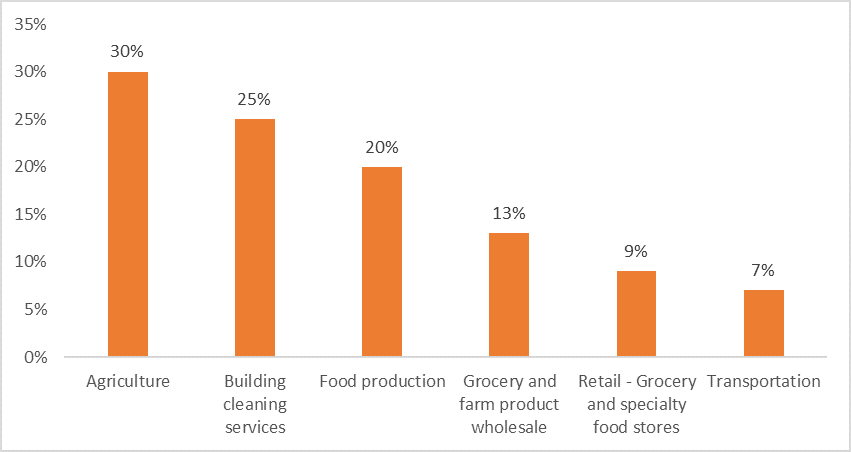

The food industry relies heavily on low-wage immigrant labor. National data reveal that 30 percent of agriculture workers, 27 percent of workers in food production, and 37 percent of workers in the meat-processing industry are foreign-born.[2] However, these estimates using U.S. Census Bureau data are likely undercounted, as data from the National Agricultural Workers Survey in 2016 show that 77 percent of the representative sample of farmworkers were foreign-born.[3] In North Carolina, 14,000 agriculture workers are foreign-born, representing 30 percent of agriculture workers in the state, according to a Migration Policy Institute analysis.[4] Other sources suggest this is also an undercount, with nearly 22,000 farmworkers alone having H-2A visas (H-2A visa holders are foreign nationals), which doesn’t include farmworkers who have other classifications.[5] In addition, 20 percent of food production workers and 13 percent of grocery and farm-product wholesale workers are foreign-born.[6] In addition, the building cleaning services industry in North Carolina is comprised of 25 percent foreign-born workers, and approximately half earn wages that put them below 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), 20 percent fall below the poverty level, and 35 percent have no health insurance.[7]

Figure 1: Immigrants perform essential work yet are excluded from much of COVID-19 relief

Percent of foreign-born workers in North Carolina by selected industry, 2014-2018 data.

Source: Migration Policy Institute and Center for Economic and Policy Research.

While some immigrants are employees, others are job creators and entrepreneurs. Nearly 62,000 immigrants in North Carolina own a business, making up about 1 in 8 business owners in our state’s metro areas, including Raleigh and Charlotte.[8] These immigrant entrepreneurs employ approximately 120,000 North Carolinians.[9]

Public policies continue to leave out immigrants

Many immigrants do this essential work in exchange for low wages, and many more have lost their low-wage jobs and aren’t receiving the support necessary to help their families through the crisis.

The combination of these factors — low wages and no health insurance — and other challenges before the pandemic meant that many immigrants already were worse off economically than other essential workers. Many of our nation’s safety net programs, which were designed to help low-income people access crucial services, were also specifically designed to exclude many categories of immigrants. This includes:

- Medicaid, the health insurance program.

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), also known as food stamps.

- Unemployment Insurance system.

- Economic impact payments, known as stimulus checks.

- Small business loans.

Medicaid, the key public health insurance program to cover low-income individuals, by federal law excludes many immigrants, including many categories of lawfully present immigrants. Non-citizens make up approximately 24 percent of the nation’s uninsured population, and many of these individuals lack an alternative option for health coverage.[10] While community health centers and other safety net components of the health care system provide vital services to many low-income and immigrant communities, they are limited to outpatient services. Ensuring access to free health services is central to an equitable COVID-19 response — given the rapid spread of the virus and its often serious consequences — yet free health services have been absent from the legislation passed thus far.

An estimated 301,000 people were excluded from receiving economic impact payments because they live in households where at least one family member files taxes using an Individual Tax Identification Number (ITIN) instead of a Social Security number.[11] It is essential to implement this targeted aid — $1,200 per adult and $500 per child age 16 and under — in an inclusive way that ensures that individuals and families can benefit regardless of how they file taxes or with whom they live.

For the thousands of immigrant entrepreneurs in North Carolina, eligibility for the Payroll Protection Program and other small business loans made available through state and federal legislation during the COVID-19 pandemic will rely largely on whether they have an existing relationship with a bank that can effectively navigate the government systems involved. Many immigrant entrepreneurs face barriers to accessing the traditional banking system that their native-born peers do not. These barriers often push immigrant entrepreneurs to the back of the line for these programs or put these supports out of reach entirely. As such, relying heavily on established relationships with banks is an indirect way of excluding many immigrant business owners, particularly those who are undocumented.

An immigrant-inclusive federal COVID-19 response should address the following:

- Public charge rules: Halt public charge regulations used by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Department of State (DOS) to decide whether a Stop any further action by federal agencies to alter long-standing policies on public charge.

- Health care: Allow all low-income immigrants in all states to receive COVID-19 testing, treatment, and vaccines through Medicaid.

- Economic supports: Remove barriers to accessing stimulus payments, nutrition assistance, and other economic supports.

- Protections from Immigration Enforcement at Sensitive Locations: Enact the Protecting Sensitive Locations Act, and ensure that people seeking health care and other needed services for their families are not deterred based on fear of immigration enforcement.

- Language access: Ensure that language access is not a barrier to learning about the availability of health care and other services or obtaining those services.

In addition to being excluded, immigrants also have been targeted. For example, earlier this year the federal government finalized a public charge rule that would significantly increase the number and type of factors that could be used to determine if someone is a public charge. This lengthy and complicated rule, along with other anti-immigrant actions championed by the Trump administration, has resulted in fear and confusion for many immigrants. Emerging data are already reflecting the intimidation that immigrant families are experiencing during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading families to avoid services for which they may be eligible.[12]

Since the pandemic began, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) has issued a public notice stating that they will not consider testing and treatment for COVID-19 in a public charge determination. However, the anti-immigrant environment has left immigrants wary of seeking services, even in the time of a global pandemic. Legislative action to protect sensitive locations from immigration enforcement actions and to halt the public charge rule would provide more assurance for families, in addition to broader federal immigration policies that protect immigrant families, such as people with DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), TPS (Temporary Protected Status), and migrant worker status.

Rather than exclude and promote fear in immigrant communities, it would benefit all of us to adopt more inclusive policies and practices. Ensuring that all North Carolinians can access the services they need — food, health care, and economic security — will ensure that they can stay home to slow the spread of COVID-19, practice safe distancing, and care for themselves and their families.

[1] Rho, H. J., Brown, H., & Fremstad, S. April 2020. A basic demographic profile of workers in frontline industries. Accessed at https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries/

[2] Migration Policy Institute. April 2020. The Essential Role of Immigrants in the U.S. Food Supply Chain. Accessed at https://www.migrationpolicy.org/content/essential-role-immigrants-us-food-supply-chain

[3] U.S. Department of Labor. 2017. National Agricultural Workers Survey. Accessed at https://www.doleta.gov/naws/public-data/docs/NAWSPAD_Codebook_2003_2016.pdf

[4] Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of U.S. Census Bureau 2014-2018 American Community Survey (ACS) data, accessed April 7, 2020 through Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas, and Matthew Sobek, “IPUMS USA: Version 10.0 [dataset].” Accessed at http://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/datahub/ImmigrantWorkersinFoodRelatedIndustries-Tables-FINAL.xlsx

[5] Unpublished data from the North Carolina Department of Commerce, Workforce Solutions, Agricultural Services, 2018.

[6] Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of U.S. Census Bureau 2014-2018 American Community Survey (ACS) data, accessed April 7, 2020 through Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas, and Matthew Sobek, “IPUMS USA: Version 10.0 [dataset].” Accessed at http://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/datahub/ImmigrantWorkersinFoodRelatedIndustries-Tables-FINAL.xlsx

[7] CEPR’s Analysis of American Community Survey, 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates. Accessed at https://cepr.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CEPR_frontline_workers_states.xlsx

[8] American Immigration Council. June 2020. Immigrants in North Carolina. Accessed at https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigrants-north-carolina

[9] Guerrero, L. May 2019. Immigrants in labor force help N.C.’s economy thrive. Accessed at https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/immigrants-in-labor-force-help-n-c-s-economy-thrive/

[10] Kaiser Family Foundation. March 2020. Health coverage for immigrants. Accessed at https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/

[11] Wiehe, M. & Gee, L. C. May 2020. Analysis: How the HEROES Act would reach ITIN filers. Accessed at https://itep.org/analysis-how-the-heroes-act-would-reach-itin-filers/

[12] Bernstein, H., Karpman, M. Gonzalez, D., & Zuckerman. S. May 2020. Immigrant families hard hit by the pandemic may be afraid to seek the help they need. Accessed at https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/immigrant-families-hit-hard-pandemic-may-be-afraid-receive-help-they-need

Justice Circle

Justice Circle