North Carolina has some big choices to make in the coming months, choices that will shape how the recovery from COVID-19 happens and what kind of state will emerge from the pandemic. Billions of dollars in federal aid from the American Rescue Plan need to be allocated, and the legislature will have to decide whether to put the additional billions we have sitting in the bank to work. The response thus far has failed to address the scope of the harm created by COVID-19 and threatens to leave our state worse off even once the pandemic has passed.

Key lessons from previous rounds of COVID-19 response:

- Aid thus far has left North Carolina more divided, unequal, and vulnerable.

- More clarity and flexibility could strengthen our response.

- Billions in state dollars could be put to work.

- Local governments need more support.

- Aid could be targeted and barriers reduced for people most in need.

- Families and individuals need more reliable aid.

- North Carolina should build for a just and resilient recovery.

If we don’t shift course, a post-pandemic North Carolina could be more unequal, economically weakened, and more vulnerable to the next crisis. Now more than a year into this pandemic, we need a different plan. We need a plan that provides a financial bridge to families who are trying to make it through the pandemic, a plan that gives public servants the resources they need to shepherd the recovery, and a plan that addresses North Carolina’s pre-existing conditions that have made the pandemic more devastating.

Lesson: Response thus far has left North Carolina more divided, unequal, and vulnerable

The unfortunate reality is that our response thus far has put already financially strained families in a deeper hole, while many wealthy people and big corporations have gotten even richer. Racial and regional economic divides have widened, the recession has been most devastating for North Carolina’s lowest paid workers, and we’ve lost years of progress in closing the economic gender gap. It didn’t have to be like this, and many policy choices made over the last year have turned COVID-19 from a shared threat into a disaster wreaking havoc along the pre-existing fault lines of our economy.

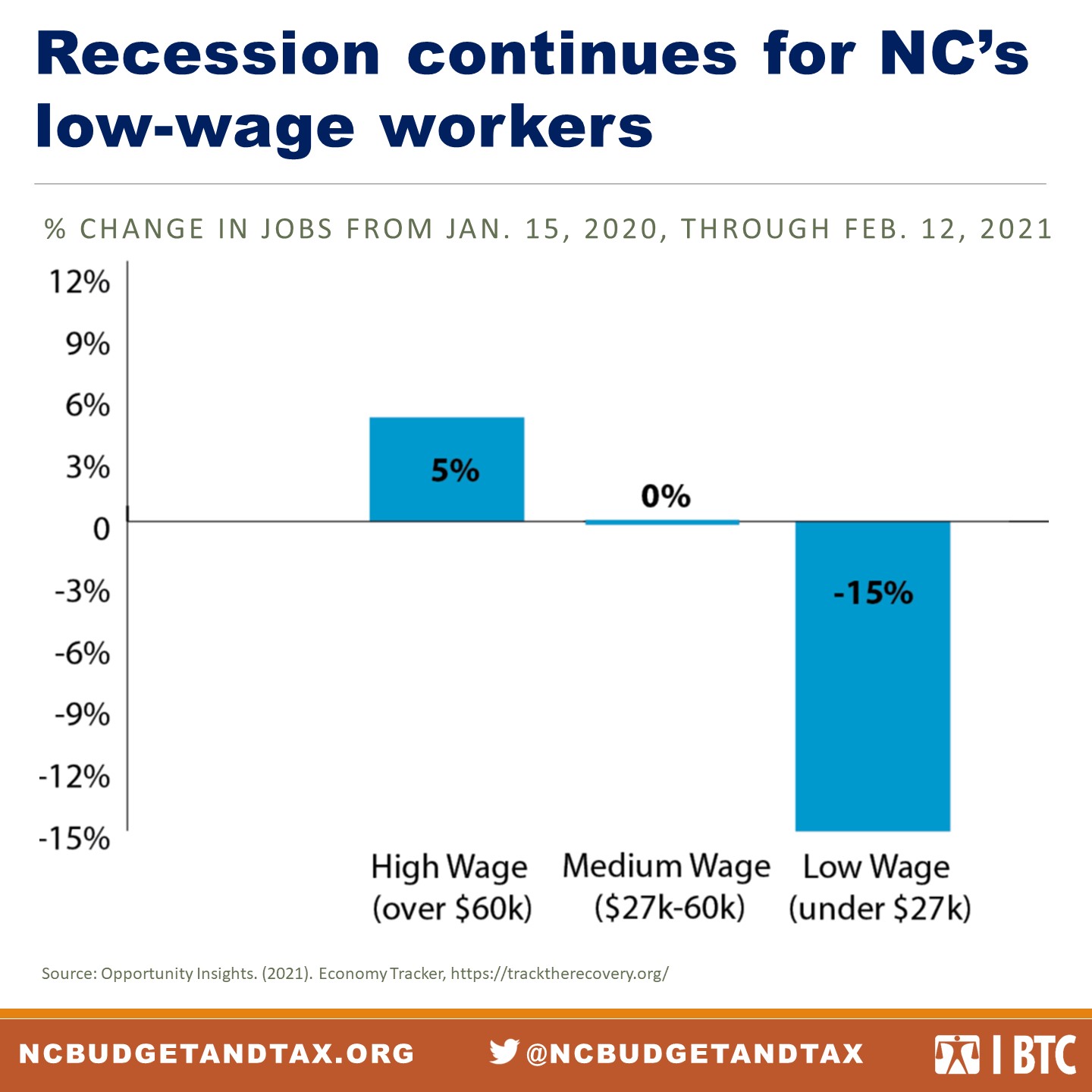

High wage recovery and low wage recession

The COVID-19 recession was extremely brief (or non-existent) for most highly paid North Carolinians, but the recession is still devastating low-income workers. In two short months from February to April of last year, nearly 270,000 leisure and hospitality jobs vanished.[1] Most of the people who were put out of work were being paid meager wages before the pandemic and so had little financial cushion. A long history of occupational segregation and barriers to lucrative careers also meant that women and people of color have been particularly likely to see their livelihoods disappear. On the other end of the wage scale, North Carolinians who work in finance, business services, technology, and other white collar positions have seen their daily lives upended, but many have been able to shift to working remotely and most have kept receiving good paychecks.

Now a year into the pandemic, high-wage and medium-wage jobs have more than recovered from the initial losses, while more than 1 in 7 of the worst-paid jobs in North Carolina are still missing.

What economists have come to call a K-shaped recovery — where the upper reaches of the wage scale recover quickly while low-wage workers struggle through a long downturn — has fully come into being. This reality threatens to deepen the divide between North Carolina’s best-paid and worst-paid workers that already existed before the pandemic.

Rural-urban gap may widen

The initial wave of job losses at the beginning of the pandemic was concentrated in North Carolina’s largest cities and regions of the state most heavily reliant on tourism. As the pandemic has gone on, however, several of the state’s most prosperous cities are recovering faster while many rural counties and mid-sized cities are continuing to experience prolonged employment declines.

If we repeat the mistakes of the Great Recession, when many communities were largely left to fend for themselves after initial aid dried up, COVID-19 could further deepen the economic divide between North Carolina’s most affluent cities and the rest of the state.

Women being driven out of the workforce

The pandemic has reversed years of progress in closing the gender gap in labor force participation. Unlike the Great Recession that hit industries where men make up a larger share of the labor force, the COVID-19 pandemic has devastated occupations that are disproportionately filled by women.

Compounding this inequity in the type of jobs that have been lost, women are far more likely to face other barriers to re-employment. By the latter part of 2020, roughly 30 percent of women who had lost a job due to COVID-19 were out of work because they lacked child care — compared with only 4 percent of men.[2]

By the latter part of 2020, roughly 30 percent of women who had lost a job due to COVID-19 were out of work because they lacked child care — compared with only 4 percent of men.

The failure to provide access to good-paying jobs plus the gender gap in who provides child care have made COVID-19 a particular economic disaster for women.

Lesson: More clarity and flexibility would strengthen our response

The General Assembly has a habit of making it hard for public servants to serve the public. Funding to address the impacts of COVID-19 was spread across multiple bills, many going back and changing how funds were previously allocated. While legislators certainly faced enormous uncertainty in the early months of the pandemic, we have had a much clearer picture for several months about the nature of the harm and the types of aid that are most needed. When all was said and done, the General Assembly allocated CARES Act funds to more than 140 distinct purposes, including a long list of narrow funding streams, special carve-outs, and onerous limitations on how funds could be used. All of this created a mess for agencies trying the fight the pandemic. Agencies and communities in need of clarity and flexibility in funding instead often faced delay, uncertainty, and resources that could not meet the need.

By holding the purse strings so tightly, the General Assembly created ongoing and unnecessary challenges for agencies, local governments, and nonprofits trying to get aid where it was most needed. After a year of legislative complexity and continually shifting priorities, the state sorely needs greater clarity and flexibility in allocating future state and federal funds.

A long and winding road

The legislature’s approach to appropriating $3.6 billion in federal funds provided through the CARES Act has hardly been straight-forward. These funds were allocated, and often later shifted around, in hundreds of line items across more than ten pieces of legislation from May of 2020 through March of this year. Some of the key moments in this long and winding road include:

- May 2020: 2020 COVID-19 Recovery Act – S.L. 2020-4: Appropriated $1.425 billion in CARES Act funds.

- June and July 2020: Multiple bills: Changes to June appropriations and $1.6 billion in new allocations.

- September 2020: Coronavirus Relief Act 3.0 – S.L. 2020-97: Changes to several previous pieces of legislation and $567 million in new allocations.

- Early 2021: S.L. 2021-1 and S.L. 2021-3: Further reallocations of funds originally appropriated in S.L. 2020-4.

For a detailed summary of funding decisions made during the first several months of the pandemic, see the 2020 Legislative Session highlights summary.

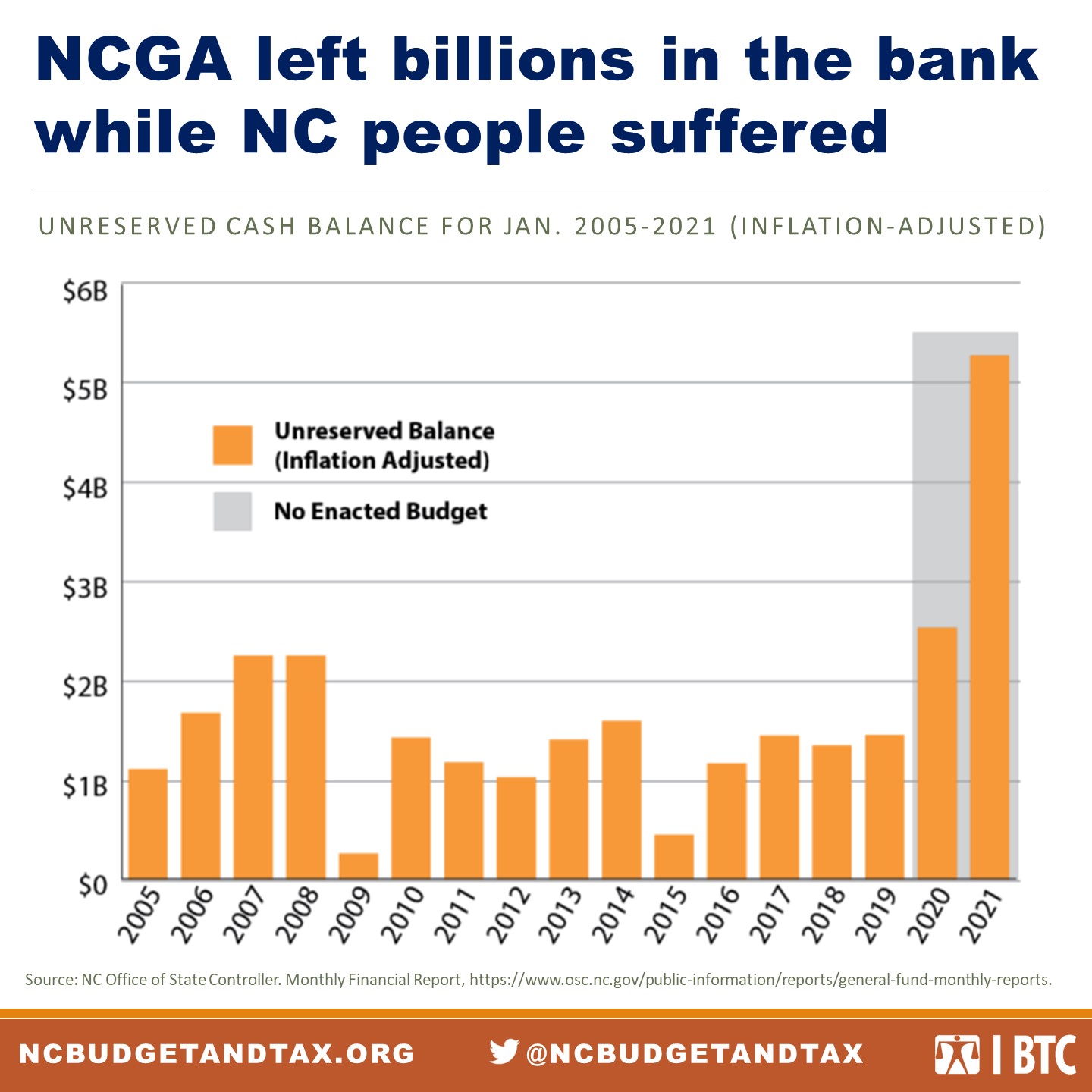

Lesson: We need to put billions in state dollars to work

The General Assembly has left billions of dollars sitting in the bank throughout this pandemic. Some of this was understandable in the early months of the pandemic when it was unclear how the recession would impact revenue collections, but it has been clear for several months now that North Carolina has the resources to invest in recovery. It’s well past time to put state funds to work addressing the harm of COVID-19 and laying the foundations for a more inclusive recovery.

Normally, a generational crisis is met with a robust public response. When the Great Recession came along, legislative leaders spent our unappropriated balance down nearly to zero, just as one would expect in the middle of an economic disaster. The response this time, however, has been strikingly different. As of January 2021, North Carolina had over $5 billion in completely unallocated funds sitting idle.

This unreserved balance is partially due to the General Assembly’s inability to pass a budget that could meet North Carolina’s needs over the past two years. State agencies were already limping along without sufficient funding even before the pandemic arrived, which makes it all the more imperative to use the funds sitting in our accounts to meet the scale of need created by COVID-19.

Use funds the state previously took off the table

The General Assembly didn’t just fail to invest state dollars; it actually diverted federal funds to replace appropriations that had been made before the pandemic. Only a few months into the pandemic, the legislature required that $645.4 million in federal funds be used to offset existing General Fund dollars for purposes that could be construed to fit within the federal guidelines for COVID response, even if these activities were already budgeted and planned before COVID-19.[3] Additional funds were reallocated to offset previously budgeted state functions, bringing the total to just under $700 million.[4] Given how little of the state’s money the legislature has appropriated to address the pandemic, this one choice means the state effectively took money off the table, reducing the impact of federal aid and more than offsetting any net new effort by the state to address the pandemic.

The practical effect of this policy decision was to add nearly $700 million to the unappropriated state funds that are currently available. Putting those funds to use in 2021 is a vital element for laying the foundations for a just recovery.

State aid is critical to filling gaps in federal assistance

Putting state dollars to work is all the more imperative given the constraints around allowable uses, the deadline for expending funds, and the uncertainty that at times surrounds what federal funds can be used to cover. State agencies and local governments have often struggled to ascertain what types of expenditures are allowable under federal guidelines, making it difficult to implement creative remedies for the problems caused by COVID-19. More flexible state aid could give authorities on the front lines the tools they need to fight the pandemic.

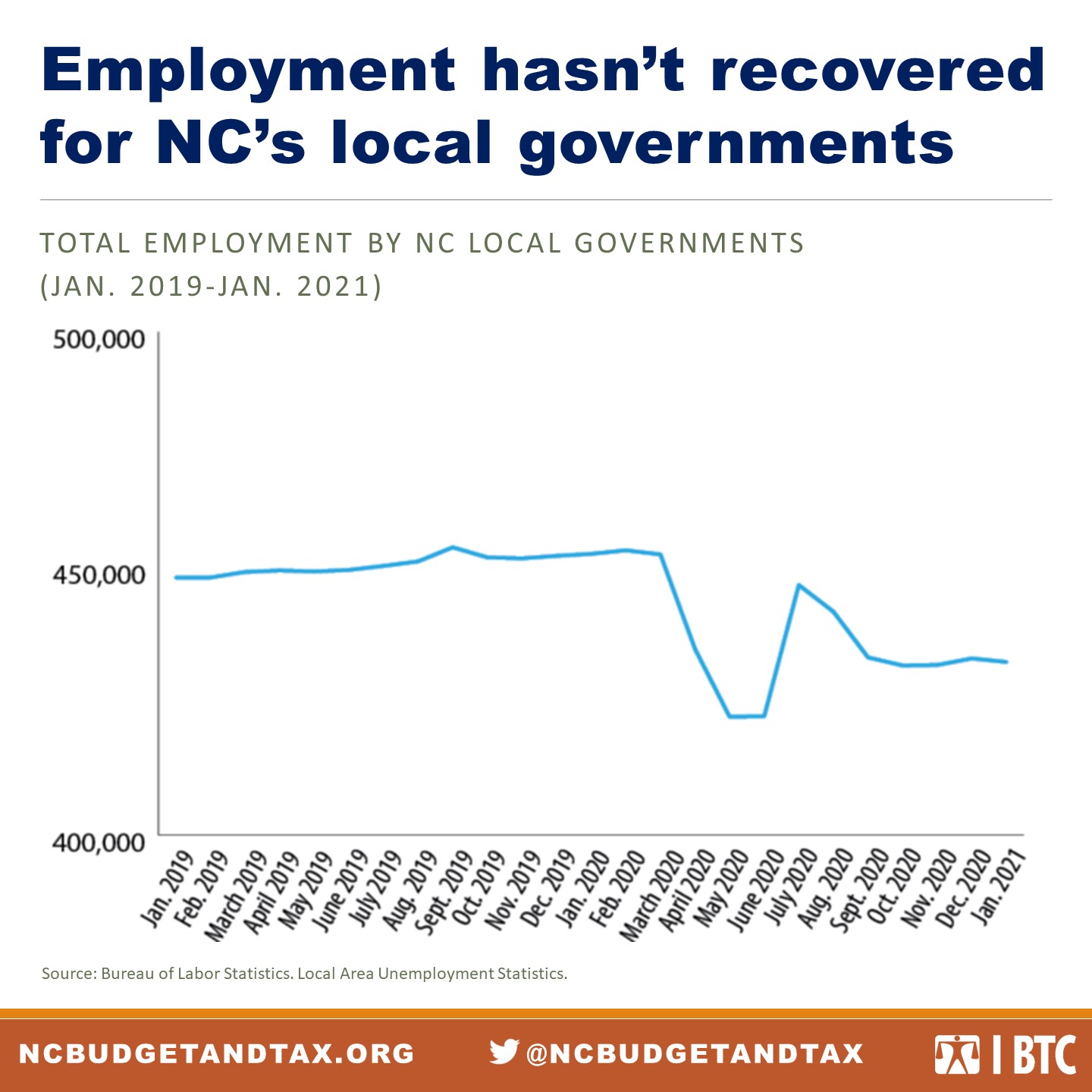

Lesson: Local governments need more support

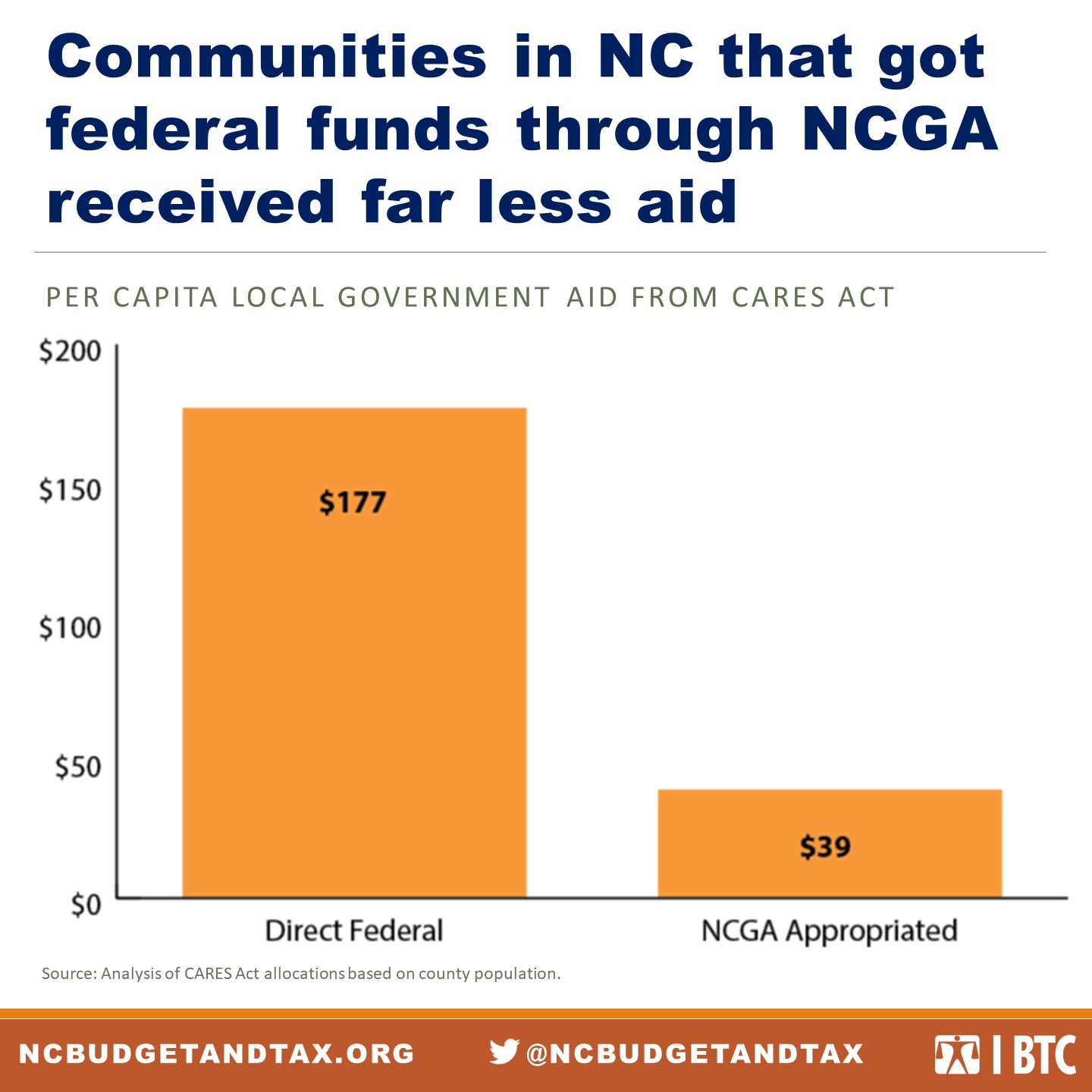

Only a few of North Carolina’s largest cities have received direct assistance from the federal government; the rest have had to rely on pass-through appropriations from the General Assembly, which have proved to be nowhere near sufficient.

The CARES Act included more than $480 million for North Carolina’s four largest local governments (Charlotte, Guilford County, Mecklenburg County, and Wake County).[5] The General Assembly appropriated only $300 million in federal funds for all other local governments combined.

This choice created an enormous imbalance between communities that received aid directly from the federal government and those that had to rely on the General Assembly. Governments representing the residents of three counties that got aid directly from the federal government received an average of more than $170 resident per resident, compared to less than $40 per resident passed along by the General Assembly to local governments representing the rest of the state. This imbalance threatens to grow the economic gap between North Carolina’s largest cities and the rest of the state that already existed before the pandemic.

A lack of aid to local governments has undermined their ability to manage this historic pandemic and contributed to a wave of layoffs of public servants. Overall, local government employment declined by over 22,000 from the start of the pandemic through early 2021,[6] with some local governments having the lay off more than 10 percent of their employees.

Lesson: Target aid and remove barriers for people with the greatest need

North Carolina policymakers can do much more to ensure that aid goes to communities experiencing the worst financial fallout from COVID-19. Without adequate pre-existing systems for delivering aid to people having a financial crisis and with little effort to fix the problem, the General Assembly sent money where it wasn’t needed and left other families struggling to survive.

Aid for people and families should be better targeted

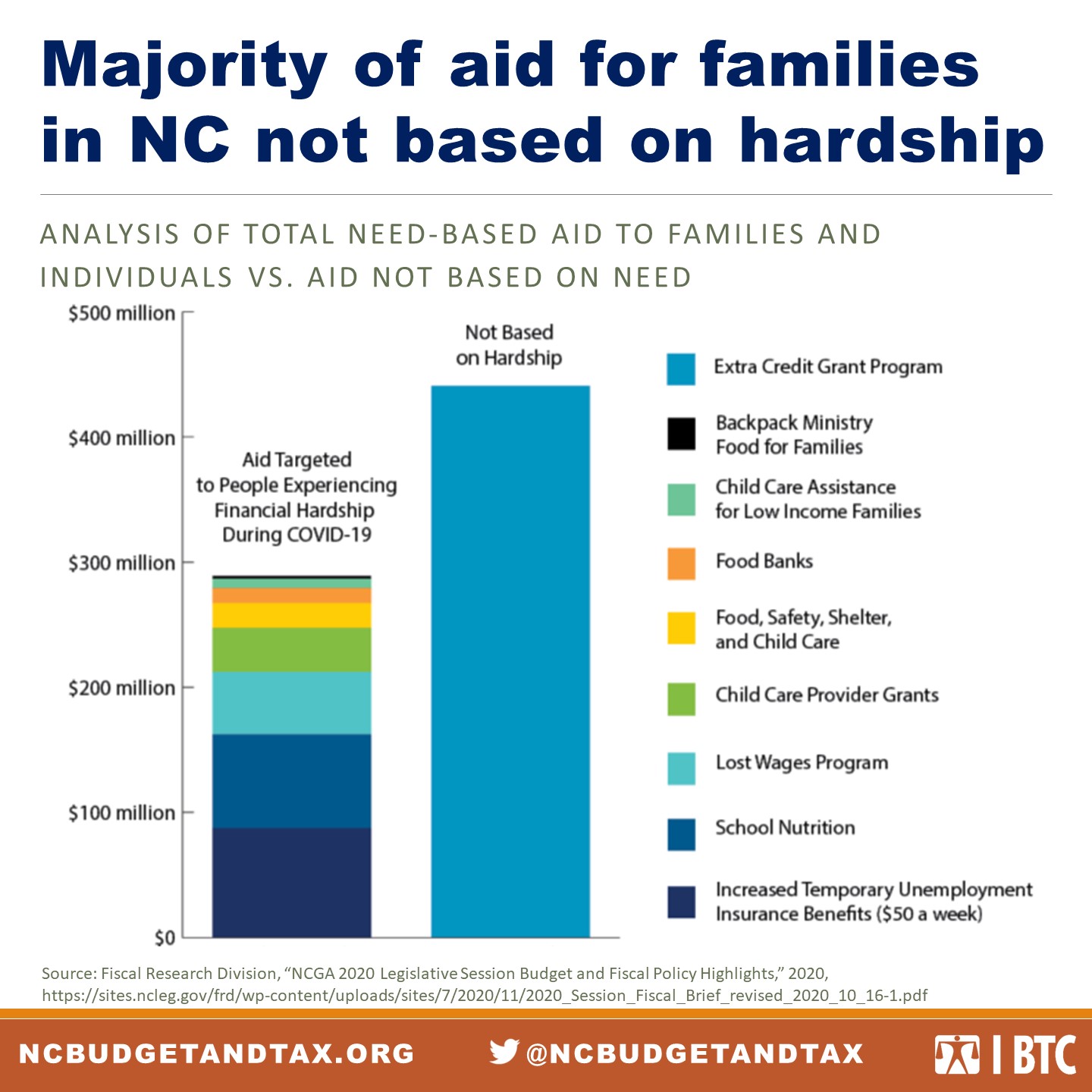

One of the largest appropriations of CRF funds last year (totaling over $440 million) failed to direct aid where it was most needed. The “Extra Credit Grant” assistance was given out regardless of whether recipients had lost jobs or faced financial hardship — diverting aid from people with the most need to families in no immediate distress. To make matters even worse, many North Carolinians in the greatest need earned too little in 2019 to file tax returns and were forced to file an additional application, but most affluent households received the $335 checks automatically. The unfortunate result was that hundreds of thousands of families in desperate financial shape did not get this small measure of assistance.[7]

The problems inherent in the Extra Credit grant program are all the more telling considering that the program eclipsed all of the direct targeted aid using CARES Act funds to people and families experiencing financial hardship during COVID-19. All told, the General Assembly approved less than $300 million in direct financial assistance from CARES Act funds to individuals experiencing demonstrated harm from COVID-19 across a number of programs, compared with more than $440 million in the Extra Credit Grants alone. Future aid should be more tailored to maximize the amount of assistance that can be provided to people, families, and communities in the most financial need.

Support businesses in the greatest need

It’s no secret that small businesses, particularly those owned by people of color, have had a particularly difficult time surviving the COVID-19 recession. While many global corporations saw record profits and larger companies had an easier time accessing assistance like the federal Payroll Protection Program, many of North Carolina’s under-capitalized small businesses have not received the assistance they needed. Because our state has under-invested in helping small businesses for years, many did not have the support needed even to access the aid that was available.

One unfortunate example is the $125 million in business loans approved in the first bill (S.L. 2020-4) allocating federal funds. Without the existing infrastructure needed to ensure that every business in need could access the program, these funds were not fully expended, even as many business owners of color and other small operators were facing bankruptcy. In spite of real efforts to overcome these barriers by entities charged with making the loans, $50 million of the original $125 million was not used and ultimately was reappropriated in late 2020 (S.L. 2020-97). The fact that these funds were not all used in the midst of so much demonstrable need underscores how pre-existing barriers to aid have frustrated the effort to help under-resourced communities during COVID-19.

The General Assembly has taken some small steps to address this issue in early 2021 by reallocating $8 million in previously unused CARES Act funds to the RetoolNC grant program,[8] which serves businesses owned by people of color and women. This type of aid, particularly when it does not weigh undercapitalized firms down with debt that might be difficult to service, is critical to sustaining small businesses still trying to find their way through the pandemic.

Lesson: Families and individuals need more reliable aid

Hardship over the last year has been greatly compounded by a lack of reliable aid for people trying to make ends meet. Families in financial peril have been forced to burn through savings, go into debt, and make painful choices as elected leaders in Raleigh and Washington have doled out assistance in slow and unpredictable ways.

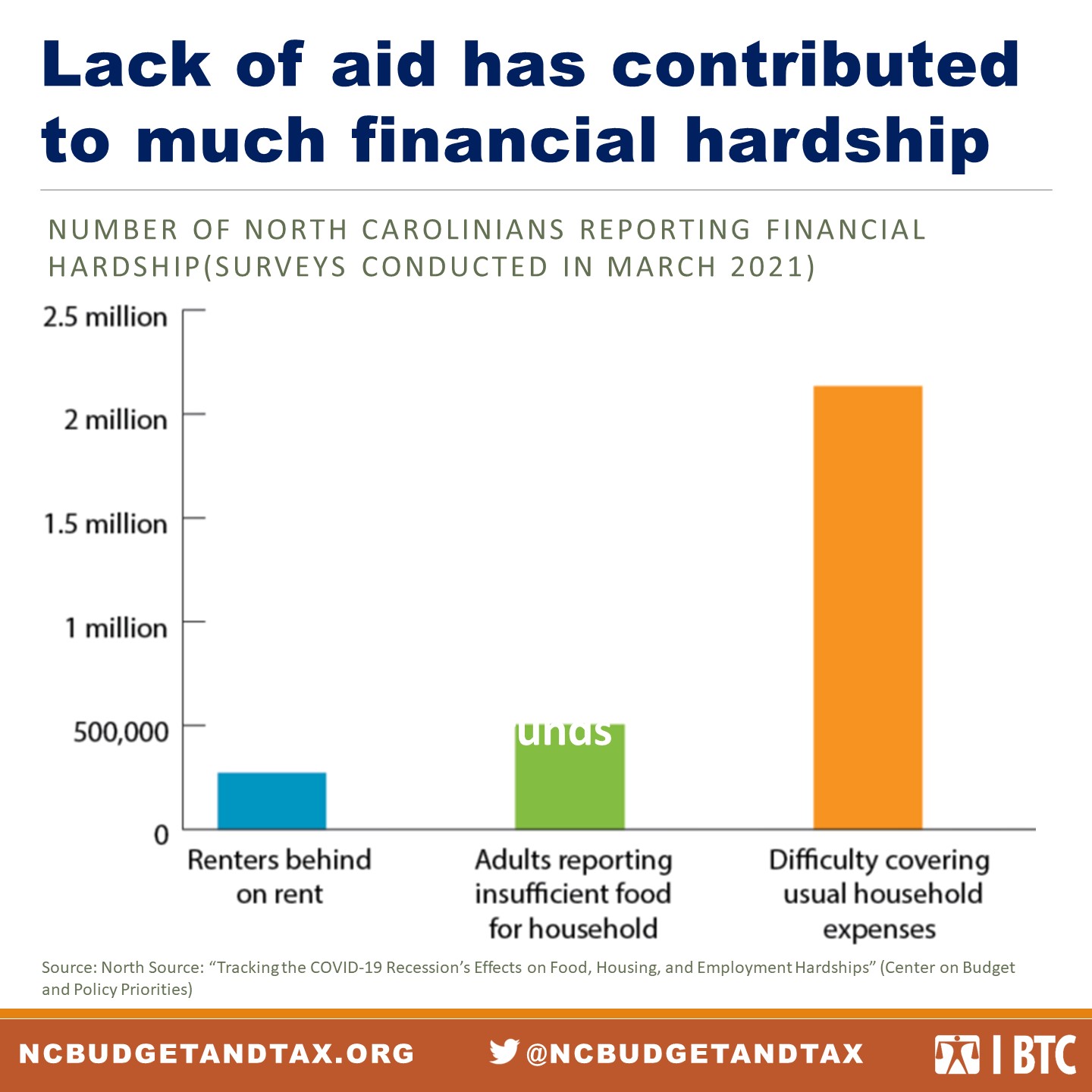

The result: Millions of North Carolinians are still having trouble making ends meet more than a year into the pandemic. Based on surveys conducted in March of 2021, more than a quarter of a million North Carolinians are behind on rent, half a million adults live in households without enough food, and nearly one-third of North Carolinians are still having difficulty paying for usual household expenses.[9]

We need a true bridge to recovery that does not leave North Carolina families dangling on the edge of a cliff. When the General Assembly allocates federal aid coming from the American Rescue Plan and appropriates state funds, it must stop leaving families in limbo.

Conclusion: Building for a just and resilient recovery

Real recovery requires a sustained commitment to rebuilding our public institutions. Trying to patch holes with one-time fixes will leave us exposed the next time that the wind kicks up, so we cannot simply look to the next few months in deciding how to build for the future. Even with more federal aid on the way, North Carolina needs a plan that will better prepare us for the next crisis.

Starving public institutions left us vulnerable

After nearly a decade of tax cuts for big corporations and wealthy families, it was no accident that so many of our agencies struggled to cope with the challenges that came with a global pandemic. Like a roof that shows its age when the hardest rains come, all of the cracks from years of neglect became far too easy to see in the middle of this storm.

The systematic underfunding of our state institutions became even worse over the last two years without new budgets to meet North Carolina’s needs. Agencies have limped along while billions of unappropriated funds have built up in the state’s bank account. As a result, public institutions already trying to meet more need than funding could address before COVID-19 were overwhelmed by the scope of hardship this pandemic created.

Examples of institutions in need of investment

- Some of the public institutions that must be strengthened include:

Unemployment Insurance: North Carolina’s underfunded Unemployment Insurance system was quickly overwhelmed by applications during the early stages of COVID-19. Even after substantial efforts to meet the need, additional reform is needed to ensure that people who have lost their livelihoods receive sufficient support during a financial crisis. - Financial aid to families in crisis: As hundreds of thousands of North Carolina families faced eviction, hunger, missing utility payments, and a host of other hardships, we often lacked the systems needed to deliver financial aid efficiently in moments of crisis.

- Child care: COVID-19 revealed the vulnerable condition of child care for working families. Already underfunded and without sufficient capacity to ensure that people don’t have to choose between working and caring for their children, North Carolina’s child care system requires deep structural reforms and increased investment.

- Under-capitalized small businesses: Even while many of North Carolina’s small businesses — particularly undercapitalized companies operated by people of color — struggled to survive the COVID-19 recession, programs quickly established to help were unable to reach many of the businesses with the greatest needs. This problem clearly shows the necessity of creating stronger systems to support entrepreneurs of color in both good and challenging economic times.

- Public health: The gaps in our public health system have become even harder to ignore. Pre-existing public health conditions greatly compounded the impact of COVID-19 and made the consequences more dire in communities that already struggled to access quality care. We need to fix our public health infrastructure so everyone regardless of race, income, or background can get the care they need.

Investing in resilient institutions

Some of the CARES Act funds have been used to expand pre-existing programs serving North Carolinians in a time of crisis, but very little has been done to strengthen public institutions for the future. Virtually no recurring funding has been allocated to increase agencies’ capacity beyond an immediate triage response to the pandemic.

There’s still time to choose a different path. We can learn from this experience to rebuild a better North Carolina — a state where people are not left to face unimaginable crises alone, where recovery does not leave communities behind, and where policy is rooted in our shared humanity.

Endnotes

[1] McHugh, Patrick, “High-Wage Recovery and Low-Wage Recession: The Targeted Devastation of COVID-19” (North Carolina Budget and Tax Center, 2021), https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/high-wage-recovery-and-low-wage-recession-the-targeted-devastation-of-covid-19/.

[2] Logan Harris, “Women’s Jobs Disproportionately Impacted by Child Care during COVID-19,” North Carolina Budget and Tax Center (blog), accessed April 7, 2021, https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/womens-jobs-disproportionately-impacted-by-child-care-during-covid-19/.

[3] “CC Funds/CIHS Funds/CR Funds and Offsets,” Pub. L. No. S.L. 2020-4 (2020), https://www.ncleg.gov/Sessions/2019/Bills/Senate/PDF/S816v5.pdf.

[4] House, “2021 COVID-19 Response & Relief,” Pub. L. No. S.L. 2021-3, 24 (2021), https://www.ncleg.gov/Sessions/2021/Bills/House/PDF/H196v7.pdf.

[5] Fiscal Research Division, “NCGA 2020 Legislative Session Budget and Fiscal Policy Highlights,” 2020, https://sites.ncleg.gov/frd/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/11/2020_Session_Fiscal_Brief_revised_2020_10_16-1.pdf.

[6] McHugh, Patrick, “NC Labor Market Figures Show Local Governments Are in Trouble” (North Carolina Budget and Tax Center, 2021), https://www.ncjustice.org/nc-labor-market-figures-show-local-governments-are-in-trouble/.

[7] Pedersen, Leila, “NC ‘Extra Credit Grants’ Program Leaves out Families with the Greatest Need,” The Progressive Pulse (blog), 2020, http://pulse.ncpolicywatch.org/2020/10/30/nc-extra-credit-grants-program-leaves-out-families-with-the-greatest-need/.

[8] 2021 COVID-19 Response & Relief.

[9] “Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships” (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities), accessed April 13, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-housing-and

Justice Circle

Justice Circle