Just as the Great Recession cast the economic mold for the 2010s, the COVID-19 pandemic and our response to it will shape the decade ahead. Faced with another era-defining economic calamity, leaders should heed the lessons of the past. The COVID-19 recession is rooted in a different underlying cause and will certainly play out in different ways, but the 2008 crisis still offers guidance on how we can speed recovery and rebuild stronger.

While hardly an exhaustive list, some of the lessons of the Great Recession include:

- Recessions are hardest on people already working to overcome barriers to opportunity.

- Helping people is the best way to boost the economy.

- Federal stimulus is vital.

- Keep helping people until the recovery takes off.

- Recessions leave dramatically different local legacies.

- North Carolina failed to rebuild stronger.

- NC tax cuts failed to boost the economy.

Social distancing paves the way to recovery

While lessons from the Great Recession are instructive now, the COVID-19 pandemic poses unique challenges that weren’t present following the financial meltdown of 2008. One vital lesson from the 1918 influenza pandemic, the deadliest in history, is that swift and sustained public health measures pave the way for economic recovery. A recent analysis by the New York Federal Reserve showed that cities where social distancing measures were implemented faster, and kept in place longer, were quicker to recover economically after the outbreak subsided. The 1918 experience thus shows that measures like closing schools, churches, and theaters, banning large gatherings, and restricting business operations did not cause additional economic harm but instead created the conditions for more robust job growth in the wake of the public health emergency. 1

Lesson: Recessions are hardest on people already working to overcome economic barriers

While the Great Recession did not target people of color, women, and low-wage workers quite as surgically as the COVID-19 pandemic has done, it still exacerbated pre-existing structural barriers to opportunity.

People of color were far more likely to lose their jobs during the Great Recession than their white colleagues,2 a pattern which may be even more pronounced in the COVID-19 recession. Where official unemployment for white workers increased by 5 percent, it shot up 7.8 percent and 6.7 percent for Black and Latinx people, respectively.

Job losses and prolonged unemployment also were far more prevalent for people who face greater barriers to educational attainment. Nationally, unemployment for workers with less than a college degree topped out near 16 percent compared to roughly 5 percent for workers with at least a bachelor’s degree.3

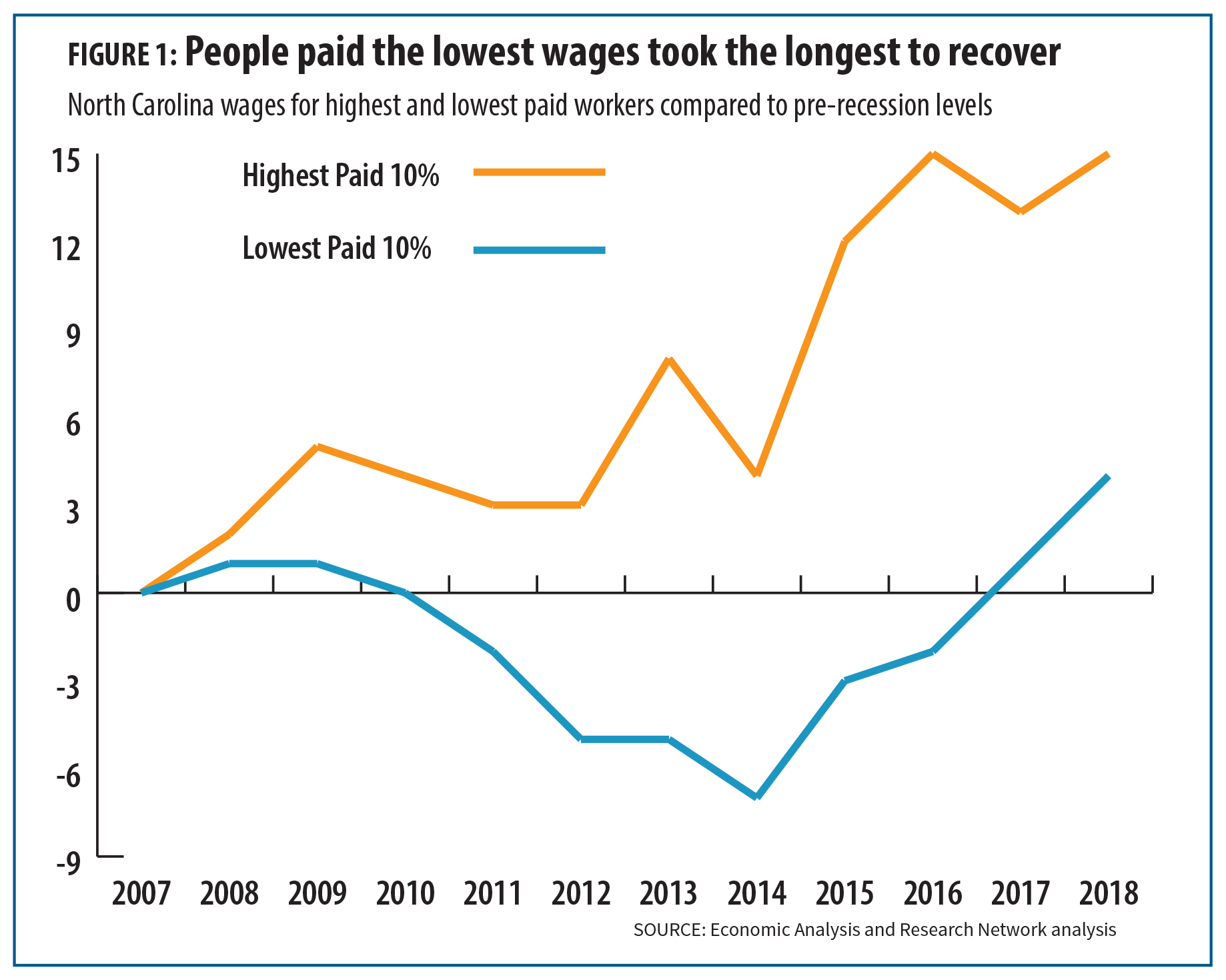

The Great Recession ravaged low-income workers’ wages for years while the most handsomely paid North Carolinians hardly missed a beat. The best-paid 10 percent of North Carolinians never actually experienced a decrease in wages, but it took a full decade for the worst-paid workers to get back to what they had been earning before the downturn.4

COVID-19 recession is targeting women

One difference between the Great Recession and the early stages of the COVID-19 downturn is that women are bearing much more of the job losses this time around. Born of failures in the financial system, the Great Recession hit industries like manufacturing and construction where men tend to occupy more of the jobs. This time around, the first wave of job losses was heaviest in occupations like retail, food service, leisure, and accommodations, where women have been significantly more likely than men to be laid off in the first several weeks of the crisis.5

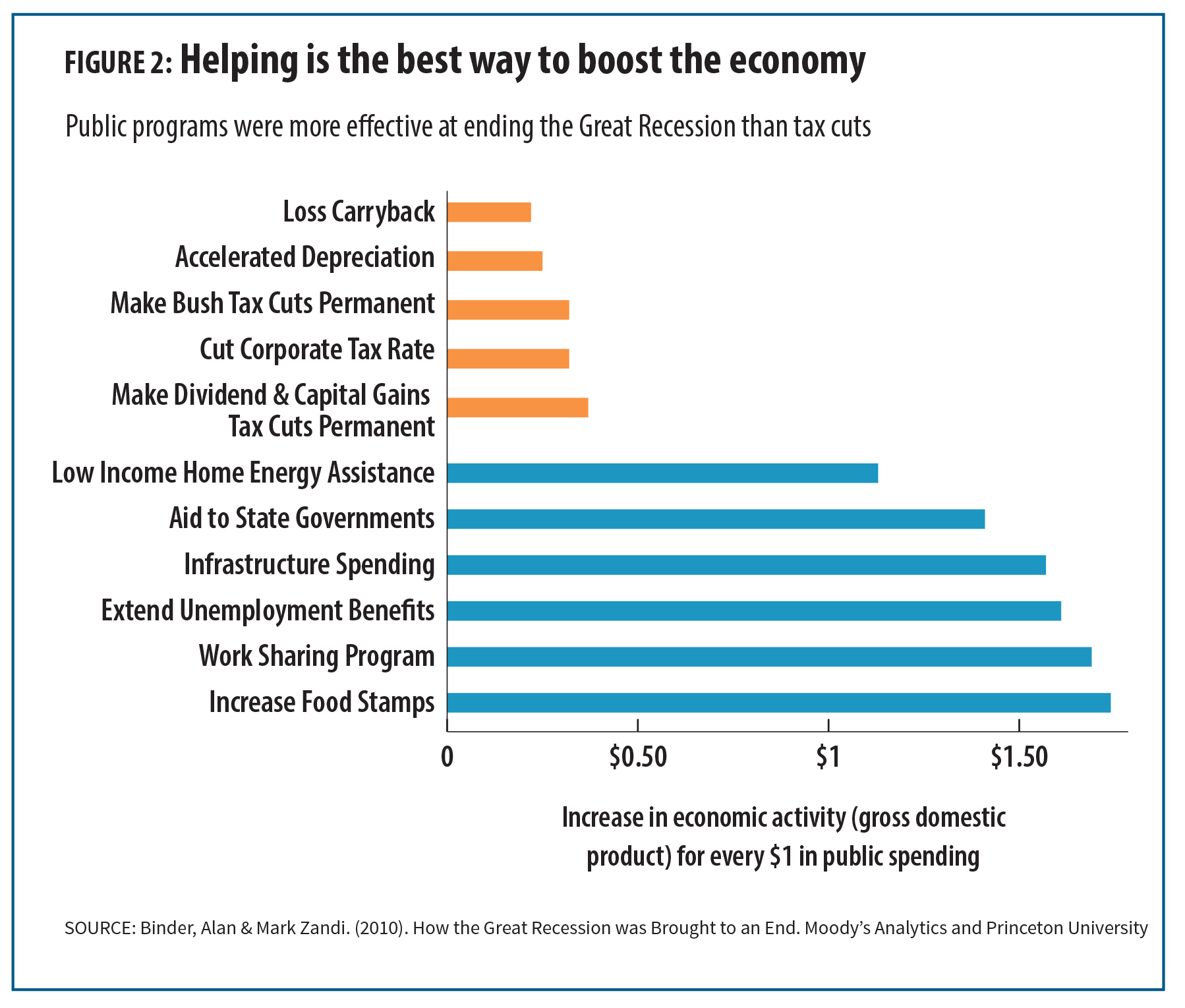

Lesson: Helping people is the best way to boost the economy

Focusing aid on people who are being harmed is the best way to resuscitate the economy at large. Federal policymakers tried a wide array of measures to jolt the economy back to life in the early days of the Great Recession, and supporting people and public investments proved to be a more effective means of boosting the economy. By comparison, tax breaks for rich investors and large companies proved to be a poor investment of public dollars.

Lesson: Federal stimulus is vital

In the throes of this current crisis, it can be difficult to remember how bleak things looked when the Great Recession began. Without the Troubled Asset Relief Program, our banking system would have collapsed under the weight of reckless and greedy behavior. Without the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, far more families, states, schools, and businesses would have gone broke.

A second Great Depression avoided

Economists with Moody’s Analytics and Princeton University estimate that without federal intervention the economic catastrophe would have been far worse, including:6

• The economy would have kept shrinking for three more years.

• Job losses would have topped 17 million, more than twice what happened.

• Unemployment would have reached 16 percent.

• We would have been in an even more vulnerable position going into the COVID-19 crisis.

Lesson: Keep helping people until the recovery takes off

Recessions cast long shadows. As can attest far too many young people trying to enter the labor market and the older workers who saw their careers disappear during the Great Recession, recovery can take years or never come at all. Recessions can permanently depress income, even to the extent of shortening lives and reducing future generations’ economic opportunities.7 Recessions also threaten educational achievement, depress private investment for years after the downturn officially ends, and dampen entrepreneurial activity.8 Given the economic scars that recessions leave behind, it’s vital to stimulate the economy quickly and to keep up the stimulus until a robust recovery is well under way.

The Great Recession provides a cautionary tale of what happens when government stimulus is too small and too short-lived. After initial steps to stop the economic hemorrhaging in 2008 and 2009, the government stimulus at both the federal and state levels largely dried up. Total per capita government spending remained depressed for years after the recession in a way that hadn’t happened in the previous three economy cycles.9 With balanced budget requirements constraining most state and local governments, Congress’s failure to extend stimulus is the key reason that economic suffering lasted for so long after the Great Recession. Failure to extend federal stimulus was compounded in North Carolina where state tax cuts for corporations and wealthy individuals further hampered the recovery.

Lesson: North Carolina failed to rebuild stronger

We can’t afford another failed recovery. While some people have prospered, the economic harm of the Great Recession still lingers for many families and communities across the state. In many ways, the post-recession economy in North Carolina was weaker, more rigged in favor of the extremely rich, more challenging for small towns and rural communities, and a daily financial struggle for millions of North Carolinians who aren’t being paid living wages.

The ‘normal’ before COVID-19 wasn’t working

- It took over 5 years from the end of the Great Recession in June 2009 for North Carolina finally to get back to the number of jobs that existed before the downturn. By that time, 30 other states already had recovered the jobs lost in the recession.

- A smaller percentage of North Carolinians were working before the COVID-19 outbreak than before the Great Recession.

- Nearly half of North Carolina’s counties (47 of 100) never recovered the jobs lost in the Great Recession.

- North Carolina’s employment growth was slower than most of our neighbors in the southeast (Georgia, South Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee) and all three states on the West Coast.

- People in the bottom half of the wage scale are paid roughly the same or less than in 2000, while the highest paid 20 percent have enjoyed significant wage growth.

Lesson: Recessions leave vastly different local legacies

While signs of the Great Recession are hard to find in some of North Carolina’s prospering communities, visible scars remain on main streets and neighborhoods across the state. Just as on the personal level, recessions tend to exacerbate communities’ pre-existing economic challenges and can accelerate long-term structural changes. For example, the Great Recession hammered manufacturing employment in North Carolina, dealing a heavy blow to many communities already striving to replace jobs being lost to offshoring and automation.

Particularly heavy economic losses are compounded and extended by undermining local governments’ ability to rebuild. Without state or federal assistance, budget shortfalls force local governments to cut back on services precisely when they are most needed. The state government took one important step to lessen this impact during the Great Recession by taking over local Medicaid matching payments, but much more assistance will be required this time around. For example, without additional state support, local Department of Social Services offices could lose capacity in the communities where the need is the greatest.

Lesson: Tax cuts failed to boost the economy

The premature retreat from federal stimulus was compounded by budget cuts in North Carolina that further contributed to a slow, lopsided, and incomplete recovery.10 Instead of using a slowly recovering economy to repair public programs that had been cut during the fiscal pinch of the Great Recession, the General Assembly embarked on wave after wave of tax cuts that mostly benefited wealthy individuals and rich shareholders. One consequence was the graduating class of 2020 has spent its entire K-12 school experience with depressed state funding, either because of the Great Recession or post-recession budget decisions. The cumulative effect of tax cuts passed since 2013 has been to drain $3.6 billion from the state’s coffers, funds which could have prepared us to cope far better with the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak.

While undermining our ability to invest in North Carolina’s future, tax cuts failed to deliver the promised economic boost. Job growth since North Carolina’s tax cuts started phasing in has lagged behind our regional neighbors like Georgia, South Carolina, and Tennessee while also falling behind states like California, Oregon, and Washington that did not embark on a tax cutting experiment.11 Cutting taxes also failed to solve the economic challenges facing much of rural North Carolina or create broad wage growth.

Footnotes

- Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner, “Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, March 30, 2020), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3561560.

- Patrick McHugh, “Women and People of Color Are Losing Jobs at Higher Rates than White Men Right Now” (North Carolina Budget and Tax Center, 2020), https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/women-and-people-of-color-are-losing-jobs-at-higher-rates-than-white-men-right-now/.

- Heather Boushey et al., “The Damage Done by Recessions and How to Respond,” in Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy (Brookings Institution, 2019), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ES_THP_AutomaticStabilizers_FullBook_web_20190513.pdf.

- Economic Policy Institute, “Analysis of State of Working North Carolina Data Library, Wages,” 2018.

- Elise Gould, Ben Zipperer, and Jori Kanda, “Women Have Been Hit Hard by the Coronavirus Labor Market: Their Story Is Worse than Industry-Based Data Suggest,” Working Economics Blog (blog), 2020, https://www.epi.org/blog/women-have-been-hit-hard-by-the-coronavirus-labor-market-their-story-is-worse-than-industry-based-data-suggest/.

- Allan Binder and Mark Zandi, “The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One” (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2015), https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/the-financial-crisis-lessons-for-the-next-one.

- Chad Stone, “Fiscal Stimulus Needed to Fight Recessions” (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2020), https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/fiscal-stimulus-needed-to-fight-recessions.

- John Irons, “Economic Scarring: The Long-Term Impacts of the Recession” (Economic Policy Institute, 2009), https://www.epi.org/publication/bp243/.

- Josh Bivins, “Why Is Recovery Taking So Long — and Who’s to Blame?” (Economic Policy Institute, 2016), https://www.epi.org/publication/why-is-recovery-taking-so-long-and-who-is-to-blame/.

- Sirota, Alexandra F, “Lessons for Next Time: How North Carolina Can Prepare for an Economic Downturn.” (North Carolina Budget and Tax Center, 2019), https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/lessons-for-next-time-how-north-carolina-can-prepare-for-an-economic-downturn/.

- Analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle