It is no accident that we’re discussing how to pay for places of learning that can inspire the next generation of North Carolinians. Years of tax cuts, broken funding promises, and inadequate resources in many communities have left many of North Carolina’s schools outdated, overcrowded, and in bad shape. Yet it is increasingly clear that where students learn matters for their educational outcomes and leaving children to learn in unhealthy, unsafe environments will have a negative impact on their well-being now and in the future as well as our state’s educational goals.

This BTC Report assesses the proposals currently on the table while providing important context regarding the decisions that produced the backlog in the first place, and proposes the need for long-term planning and solutions that can sustain investments in the future.

Dire need for increased investments in school buildings

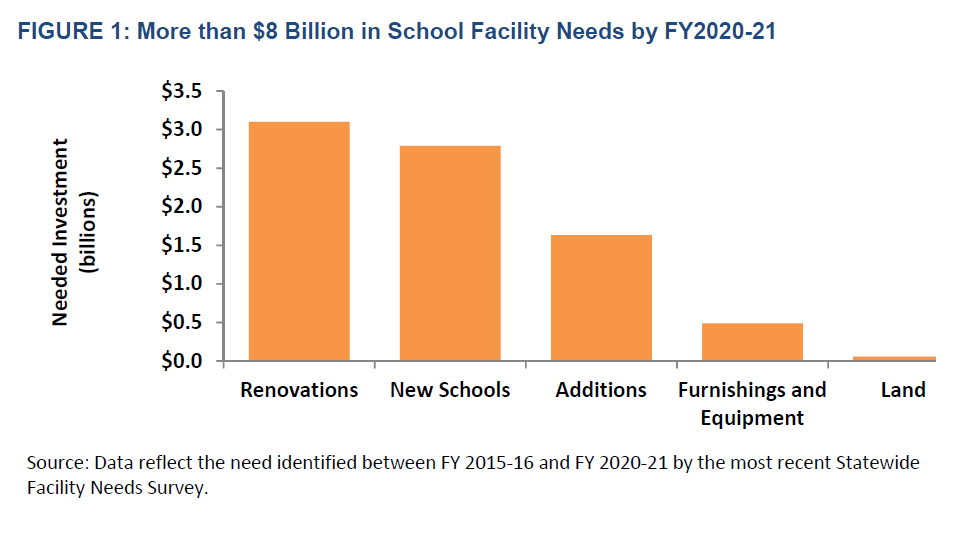

North Carolina has a massive backlog in needed school building investments. According to the most recent survey of school facility needs conducted in 2016, we need to invest more than $8 billion in North Carolina’s schools by fiscal year 2020-2021. There is an urgent need for more investment across a range of projects in communities facing very different demographic and fiscal challenges. The $2.8 billion needed for new school construction and $1.6 billion for additions are largely driven by rapidly growing populations in some urban parts of the state, creating the need for additional school facilities. At the other extreme, a large portion of the $3.1 billion in needed repairs exists because many economically struggling communities lack funds to fix aging and dilapidated school buildings.

There is an urgent need for more investment across a range of projects in communities facing very different demographic and fiscal challenges. The $2.8 billion needed for new school construction and $1.6 billion for additions are largely driven by rapidly growing populations in some urban parts of the state, creating the need for additional school facilities. At the other extreme, a large portion of the $3.1 billion in needed repairs exists because many economically struggling communities lack funds to fix aging and dilapidated school buildings.

Tax cuts responsible for the backlog

The sorry state of North Carolina’s schools is a self-inflicted wound. Several rounds of tax cuts passed by the General Assembly since 2013 have reduced state revenues by approximately $3.6 billion a year and driven state spending as a share of personal income to a 45-year low.

This rash of tax cuts has dramatically undermined our ability to deliver needed services for North Carolina’s growing population. Inflation-adjusted public school funding per student is down 5 percent from pre-recession levels, a clear sign that we have not kept up with the educational needs of a growing population. Even compared to the depths of the Recession, North Carolina schools today have fewer teachers, assistant principals, instructional support personnel, teacher assistants, and supplies. Had leaders chosen a different path that did not undermine state funding, we could have kept pace with both school construction and operating needs.

K-3 Class size requirements

Existing data almost certainly underestimates schools’ actual capital needs. Since 2015, construction costs have outpaced general inflation.5 Additionally, the North Carolina General Assembly passed an unfunded mandate for districts to reduce class sizes in grades K-3. Although there is no statewide estimate of the additional costs created by the class-size mandate, several districts have estimated the impact. For example, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools estimate needing more than 200 additional classrooms to meet the new class-size requirements. This is the equivalent of about five new elementary schools, or $20 million worth of mobile units.

Decrease in dedicated capital funding from corporations

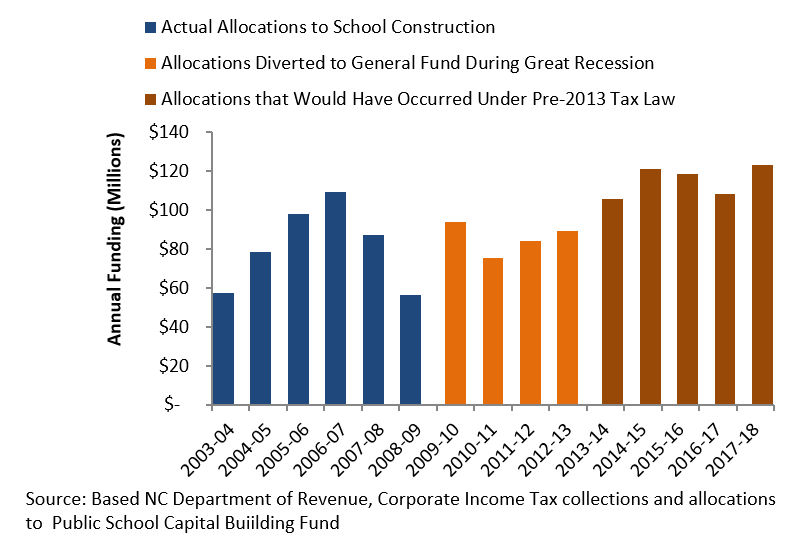

North Carolina used to support school capital by allocating a portion of corporate income tax and lottery revenue, but recent tax and funding decisions by lawmakers have dramatically reduced state investments in school construction and repairs.

From 1987 to 2009, the state dedicated approximately 7.25 percent of corporate income tax revenues to school capital through the Public School Building Capital Fund (PSBCF). When the Great Recession hit, the General Assembly decided to redirect PSBCF funds to fill the large budget shortfall created by the economic downturn. Then in 2013, lawmakers decided to eliminate the corporate income tax transfer altogether to pay for part of the cuts to corporate and personal income tax rates. Diverting the allocation between FY 2009-10 and 2012-13 meant $342 less in school construction funding. If the state had maintained the corporate income tax policy that existed before 2013, it would have generated an additional $576 million in funding for school construction through the 2017-18 Fiscal Year.

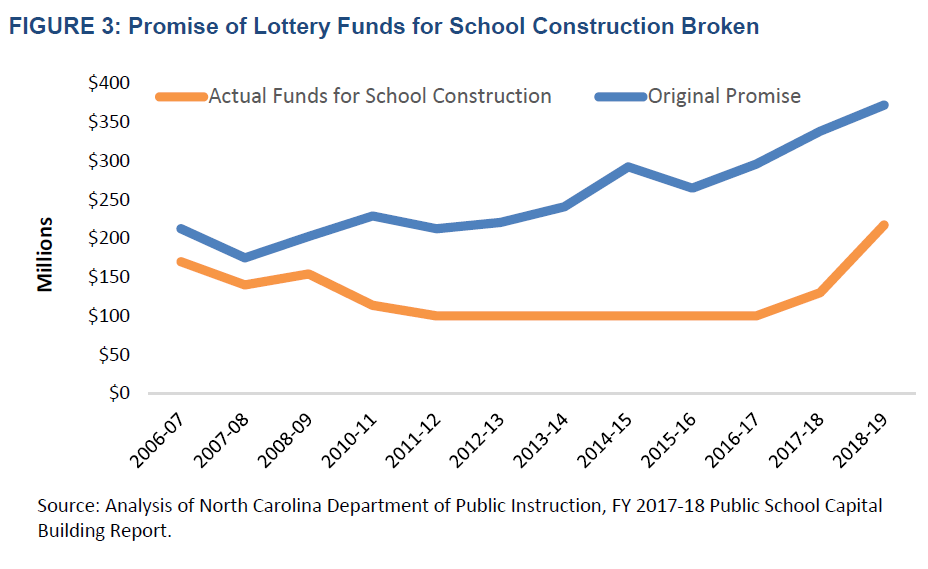

In 2006, the establishment of the lottery created a second revenue source for school capital. The original lottery legislation in 2005 would have directed 50 percent of available lottery revenue to the PSBCF. That percentage was reduced to 40 percent when the lottery was ultimately implemented via the 2005 budget bill. In subsequent years, lawmakers disregarded the 40 percent requirement and the percentage of lottery revenue dedicated to the PSBCF continued to fall. In 2013, the General Assembly permanently removed the requirement that 40 percent of lottery funds would be dedicated to the PSBCF.

In 2006, the establishment of the lottery created a second revenue source for school capital. The original lottery legislation in 2005 would have directed 50 percent of available lottery revenue to the PSBCF. That percentage was reduced to 40 percent when the lottery was ultimately implemented via the 2005 budget bill. In subsequent years, lawmakers disregarded the 40 percent requirement and the percentage of lottery revenue dedicated to the PSBCF continued to fall. In 2013, the General Assembly permanently removed the requirement that 40 percent of lottery funds would be dedicated to the PSBCF.

Schools would have received an additional $1.5 billion in state support for capital projects over the lottery’s first 12 years if lawmakers had kept their promise to dedicate 50 percent of lottery revenue to capital.

Schools would have received an additional $1.5 billion in state support for capital projects over the lottery’s first 12 years if lawmakers had kept their promise to dedicate 50 percent of lottery revenue to capital.

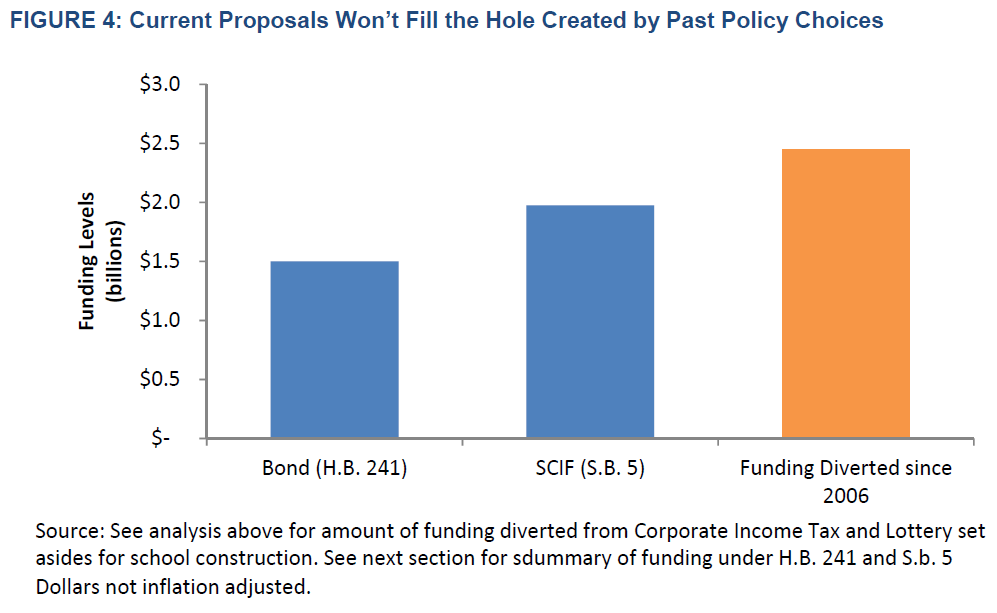

Taken together, changing corporate income tax policy and diverting lottery funds originally pledged for K-12 building has done more to harm our public schools than either of the proposals currently being discussed to do would help. Between changes to the corporate income tax and failures to deliver on promised lottery funding, the General Assembly has diverted nearly $2.5 billion from school construction funding since 2006, digging a hole that neither of the current proposals being debated can fill. The gap is actually even larger than this comparison would

make it seem because inflation and escalating costs from deferred repairs have not been factored in.

Lopsided economic landscape is making it harder for many communities to meet school building and repair needs

An increasingly unbalanced economic landscape makes the decline in state funding for school capital projects particularly devastating. The concentration of economic growth in a handful of urban areas across the state is undermining the ability of many small town and rural communities to cover the costs of updating and upgrading their school facilities. We are now more than 11 years out from the start of the Great Recession, and 49 of North Carolina’s counties have still not recovered to the number of jobs that existed before the economic wheels came off, and 23 counties actually lost jobs during 2018.1 This lack of job growth translates directly into financial challenges for many local school districts because it undermines property and sales tax collections in many of the communities with the most dire school building needs.

Like many educational issues, school capital is one with disparate racial and economic impacts. In North Carolina, there’s strong evidence that Black students are more likely to attend dilapidated schools than white students. The average Black student in North Carolina attends a school district with $2,548 of school refurbishment and equipment needs per student, compared to white students where the refurbishment and equipment needs are $2,440 per student. Students in counties with low tax bases face per-student refurbishment and equipment needs of $4,646, compared to just $2,382 in high-wealth counties.

Evaluating the Alternatives

Legislators are currently debating two proposals to direct additional state money to public school capital needs. House Bill 241 would issue bonds to fund school capital needs, while Senate Bill 5 is a “pay-as-you-go” model, earmarking General Fund revenue to public school capital. The plans differ in how they would pay for increased school construction, but share two important features:

- Both plans would reduce funding for state needs other than school construction. Neither plan raises additional revenue, so paying for school construction necessarily means reductions in other areas of the budget, including

operating funding for K-12 education. - Neither plan will fully address the scope of North Carolina’s school building needs. Both plans could potentially make an important contribution, but neither option will meet all of the needs facing our public schools. Moreover, neither plan will address school building needs beyond the next decade.

H.B. 241: School Bonds

H.B. 241 would ask North Carolina residents to vote on issuing $1.9 billion in bonds, with $1.5 billion going to K-12 school building needs and the remaining $400 million split evenly between the University of North Carolina and Community College systems.

North Carolina has the capacity to issue bonds for school construction without endangering our credit rating, and capital investments like school construction are the type of expenditures that state and local governments often use bonds to address. The state last issued bonds for school construction in 1996 and has issued debt for a variety of other purposes since then.

As noted already, repaying the debt would reduce funding for other state services, including education, but the current bond proposal has a few structural advantages:

- Certainty: Bonds create a guaranteed revenue stream that can’t be re-directed by future legislative action. School districts will know how much money to expect, allowing for long-term capital planning necessary to meet each district’s needs. Knowing ahead of time precisely how much funding they will receive helps school districts to plan construction activities, particularly for larger school building projects.

- Established allocation formula not subject to yearly budgetary negotiations: A bond would create a set formula for distributing funds across all school districts. Legislators would not be able to play politics and shift funding from one district to another based solely on political concerns.

S.B. 5: Increase Earmark to State Capital and Infrastructure Fund (SCIF)

In 2017, the General Assembly created the State Capital and Infrastructure Fund (SCIF). Under current law, the SCIF dedicates 4 percent of General Fund revenues each year to debt service and state capital needs. SCIF funds are first used to pay off debt from bonds that have already been issued and any remaining funds can be appropriated to capital projects for state agencies and UNC campuses.

In January 2019, Senate leaders introduced S.B. 5, which would increase General Fund transfers to the SCIF and allow these funds to be used for public school and community college capital projects. If S.B. 5 were to become law, 4.5 percent of General Fund revenue would be transferred to the SCIF each year. The law also says it would be the intent of the General Assembly to annually appropriate one-third of SCIF funds to public schools, one-third to higher education, and one-third to state agencies through the 2027-28 fiscal year. The proposed distribution of SCIF funds is not binding on future legislatures, which raises two concerns:

- Not guaranteed: There is no guarantee that the state will maintain its commitment to school capital under S.B. 5. As we have seen from the lottery, there is no guarantee that future lawmakers won’t simply re-direct these funds to other purposes. In fact, S.B. 5 breaks the state’s “commitment” to appropriating one-third of SCIF funds to public schools in its very first year by mandating that SCIF funds be appropriated to specific state agency and UNC system capital projects. There is very little reason to believe the amounts promised for school capital under S.B. 5 will be met. Year-to-year uncertainty of SCIF revenues would make it impossible for school districts to conduct long-term capital planning if the SCIF becomes the state’s primary strategy for supporting public school capital.

- Allocations subject to yearly political pressures: Under S.B. 5, funds will be allocated to school districts on a case-by-case basis rather than via a formula. Policymakers will be able to exert political pressure to ensure funds are provided to favored districts, rather than providing funding to all districts in accordance with need.

Comparing H.B. 241 and S.B. 5: Impacts of K-12 Construction and Operational Funding

These two plans cannot be effectively compared without taking two core considerations into account.

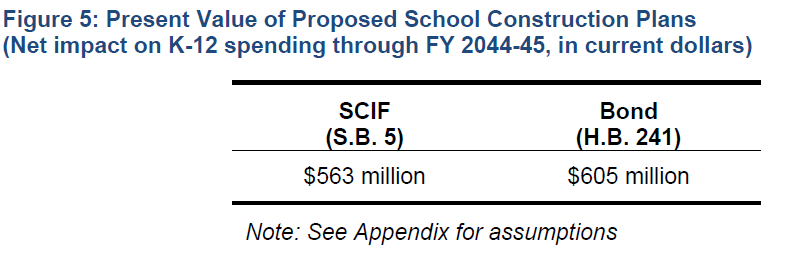

First, the different timing at which funds will be made available mean that the dollars involved cannot be directly compared. With construction costs rising faster than inflation, a dollar invested today will buy more than a dollar invested next year. As any business would do when considering long-term capital investments, a net present value analysis allows a true comparison of the buying power of each plan.

Second, we have to consider how each plan will reduce funding for other educational needs. Both plans will shift revenues from the General Fund to pay for school construction, which comes at the expense of funding for operating our K-12 system. Under H.B. 241, servicing the debt would reduce General Fund availability in future years. S.B. 5 reduces availability to meet other state needs by earmarking an additional 0.5 percent of General Fund revenue into the SCIF. Typically, almost 40 percent of General Fund revenue is spent on public schools so it is likely that a substantial portion of the General Fund reductions under either plan will come out of the K-12 operating budget.

Because of these two practical realities, a net present value analysis was conducted that accounts for the likely impact of both plans on overall K-12 funding in current dollars. This value tells you – given the cash flow projections of each plan – what the equivalent lump-sum appropriation in today’s dollars would be.

As currently written, both plans would have a net positive impact on total public school funding for buildings. Over the next 26 years (the time period over which the school bonds would be fully repaid), school bonds as proposed by H.B. 241 would provide school districts with the equivalent of over $605 million in today’s dollars, while S.B. 5 would generate somewhat less at $563 million.

The school bond would have the most dramatic positive impact on overall K-12 funding in the next seven years, while the changes proposed by S.B. 5 would provide schools with a net funding increase for nine years. Starting in Fiscal Year 2026-27, debt repayment on bonds would result in a negative impact on school funding, which would slowly disappear as the debt is retired. The S.B. 5 proposal, by comparison, would not generate a net negative impact on K-12 funding until 2029-30, but that impact would remain as long as an additional 0.5 percent of revenue is siphoned off from the General Fund into the SCIF.

The school bond proposal would provide schools with a larger near-term spending boost than the S.B. 5 proposal. The net present value analysis shows that the immediate impact of the bond is likely to be larger than the increased earmarks to the SCIF. Over the next five years, H.B. 241 would provide school districts with the equivalent of $888 million in today’s dollars, compared to $460 million in today’s dollars under S.B. 5.

It is worth noting that eliminating the SCIF altogether would have an even larger positive impact on K-12 funding. While it would not directly address school construction and repair needs, repealing the SCIF could increase appropriations to K-12 education by more than $100 million in the next fiscal year, and would make billions in additional funds available over the next few decades. While the potential benefit to public schools’ operating budgets could be substantial, it is important to note that a substantial portion of the funds currently flowing through the SCIF would still need to be used for debt service and other state capital investments.

In summary:

- Both H.B. 241 and S.B. 5 would increase overall funding for public schools.

- Both H.B. 241 and S.B. 5 would reduce operating funding for public schools and other

state services. - The bonds proposed by H.B. 241 would likely provide public schools with the greatest benefit, particularly if future General Assemblies redirect SCIF funds to other priorities.

- Neither proposal will fully address the school capital building needs or address underfunding of non-construction needs.

Impact of H.B. 241 & S.B. 5 on Universities and Community Colleges

The UNC System and the North Carolina Community College System would also receive capital funding under both plans. Unfortunately, it is impossible to use a net present value analysis to measure how these systems fare under the two proposals due to two unknowable variables:

There is no way to know how much capital funding UNC campuses should anticipate under current law via the SCIF. Under current law, UNC campuses must compete for SCIF funds against other state agencies on a project-by-project basis, making it difficult to anticipate expected revenue.

There is no way to know how UNC and community colleges would split SCIF funds under S.B. 5. S.B. 5 appropriates one-third of available SCIF funds to institutions of higher education, but does not specify how those funds would be apportioned between the two systems.

Additional Revenue is the Sustainable Solution

Both the SCIF and school bond proposals share one glaring omission: neither of the current proposals would raise additional revenue to pay for school construction needs and thus ensure an ongoing solution is in place to the challenge of financing capital needs.

Without raising additional revenues, servicing the debt on a school bond or increasing General Fund earmarks for school building appropriations will force more cuts in other areas, including education. The General Assembly has already slashed funding for a range of non-capital educational needs, including teachers assistants, textbooks, and classroom supplies, so any additional cuts to pay for school construction would only worsen an already dire situation.

Rolling back tax cuts made in the last several years could completely address our school building needs without undermining funding for education and other state services.

As noted already, if we had maintained the corporate Income tax policy that existed prior to 2013 we would have already generated around $575 million in additional school construction funding. Returning to the pre-2013 corporate income tax arrangement would generate far more funding for school construction over the next few decades than either of the plans currently being debated, and would do so without undermining funding for education and other state services.

Simply rolling back the corporate and personal income tax cuts that took effect in January 2019 (moving the personal income tax rate from 5.25 percent back to 5.499 percent and the corporate income tax rate from 2.5 to 3 percent), would raise approximately $900 million in additional revenue, more than enough to pay for both increased yearly appropriations and repaying the proposed bond for school building needs.

If the tax cuts that phased in this year were rolled back, and those funds devoted to school construction, North Carolina would erase our school building backlog within the next decade. If all of the personal and corporate income tax cuts that have passed since 2013 were rescinded and those funds reallocated to school construction, we could address North Carolina’s needs in just over two years.

North Carolina can afford safe and inspiring schools if the most fortunate North Carolinians invest more in our children’s shared future. The only question is whether leaders in Raleigh have the will to fund schools without undermining other important educational needs.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle