Economic mobility, the ability of a person to move up and out of economic classes, is the linchpin of the American dream. And yet where one lives and the level of resources their families have at birth can determine their ability to move up and out of poverty, according to high-profile research from the Equality of Opportunity Project and a body of research into neighborhood effects of poverty and toxic stress effects of poverty on children.

North Carolina, like other Southern states, has consistently ranked low on measures of economic mobility and high on measures of economic hardship.

In North Carolina, 1 in 5 children experienced poverty last year. More than 4 in 10 children who grew up in poverty are likely to remain there as adults. Growing up in a high-poverty community has lasting effects on earnings, even for those who move out of poverty and for those who do not live in poverty during childhood.

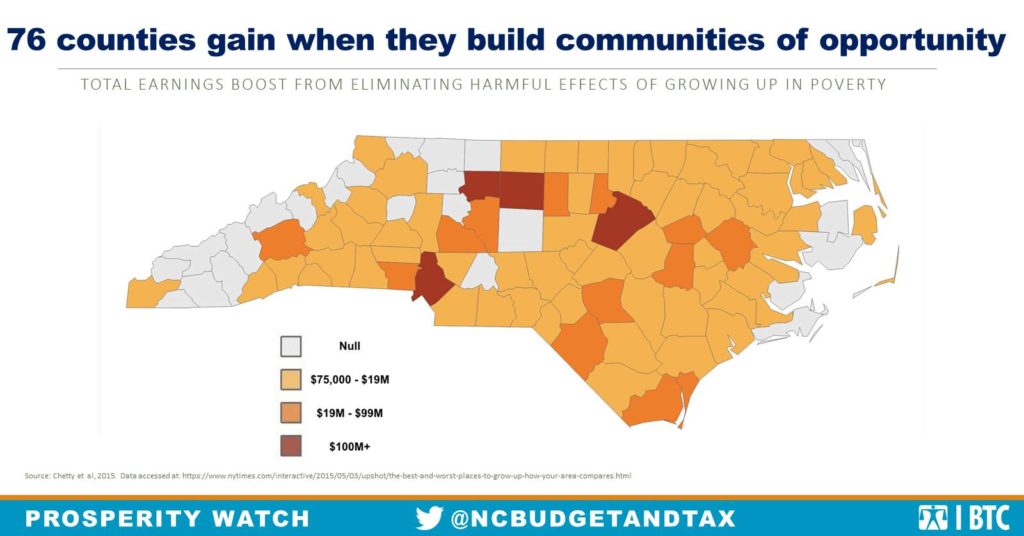

Raj Chetty and other researchers with the Equality of Opportunity Project released analysis in 2015 quantifying the earnings impact at age 26 of growing up in poverty by county in North Carolina. Specifically detailing the monetary impact of a county on poor children’s earnings relative to poor children in other parts of the country, this analysis provides insight into the economic boost possible if communities commit to eliminating just the harmful effects of the experience of childhood poverty in a given place.

According to this data for North Carolina, Forsyth County has the highest earnings penalty for children growing up in poverty, at $6,200 less in earnings at age 26, compared to poor children nationwide. Davie, Stokes and Stanley counties all provide the foundation for poor children to earn more in their community at age 26 compared to poor children nationwide. A full 76 counties would benefit from ending county income differences that result from growing up in poverty, while poor children in just 16 counties don’t experience a negative penalty relative to what poor children in other places around the country experience. The researchers find that places with low-income inequality, less concentration of poverty, and better schools have better earnings outcomes.

In combination with additional research into the neighborhood effects and effects of children of living in poverty, there are clearly broad benefits of policies and systems that minimize the worst effects of poverty on children and strengthen the pathways out of poverty for families through good jobs, affordable basics, and a high-quality education. In North Carolina, the total boost to the state’s economy of minimizing the harmful effects of childhood poverty would be $1.4 billion more in earnings circulating in our communities.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle