Millions of North Carolina workers lack paid sick days protections as COVID-19 spreads, forcing them to choose to between earning their paycheck and keeping themselves, their families, and their coworkers healthy. Paid sick leave has long been recognized as a key tool that helps reduce the spread of contagious illnesses in the workplace1 —sparing coworkers and customers alike—and makes it less likely parents will send sick kids to school or child care.2

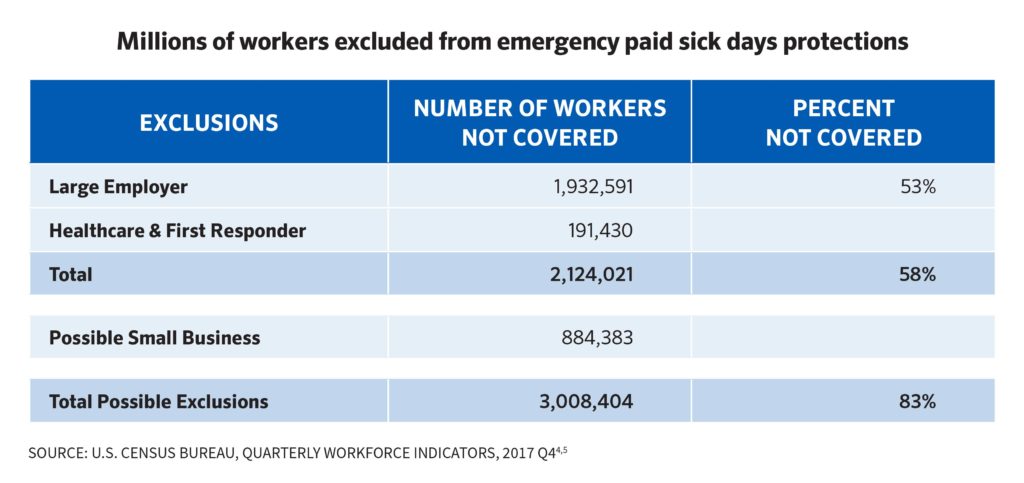

Given the intensely infectious nature of COVID-19, paid sick days play an essential role in halting the spread of the disease by allowing workers to take time away from work without losing wages. Yet recent federal action on this has fallen significantly short of what the moment requires. Although federal legislation passed in March created paid sick days protections for many workers, it included so many loopholes, exclusions, exemptions, and waivers that between 58 and 83 percent of North Carolina’s workforce—up to 3 million workers—will have no guaranteed access to these vital protections during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even more troubling, the lack of paid sick days will hit women and workers of color disproportionately hard, as these workers are over-represented in frontline and essential occupations that both lack employer-provided paid sick days and are exempt from the new federal protections. Both state and federal policymakers must close these loopholes soon, to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus across large swaths of the state’s workforce.

Millions of North Carolina workers excluded from guaranteed paid sick days

Recent federal actions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have provided some good news for many North Carolina workers—for the first time in the country’s history, the U.S. has created guaranteed and job-protected paid sick days for some of the nation’s workers. The problem, however, is that far too few Tarheel workers will benefit—between 58 percent and 83 percent of private-sector workers in North Carolina (as many as 3 million) are facing the COVID outbreak without guaranteed access to paid sick days.

The Families First Corona Virus Response Act leaves out millions of NC workers

In its second COVID-19 response package, the Families First Corona Virus Response Act, the U.S. Congress created the Emergency Paid Sick Leave Program. While a good first step, the act includes several major loopholes that will leave millions of North Carolina workers without access to paid sick days protections, just as COVID-19 cases continue to rise across the state.

The act provides up to 80 hours of job-protected (and federally-financed) paid time off for workers at their regular rate of pay in cases where they are unable to work because of quarantine (pursuant to federal, state, or local government order or advice of a health care provider), or experiencing COVID-19 symptoms and seeking a medical diagnosis.3 Workers are also entitled to the same 80 hours at two-thirds of their pay to care for quarantined family member of a child whose school or child care provider is closed or unavailable for reasons related to COVID-19. The program applies to all public sector workers and some private-sector workers, and in all cases, the costs for the leave are covered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, not the employers.

In Families First’s fine print, however, lie a number of unfortunate exclusions and exemptions that significantly reduce access to the program, and thus the paid sick days protections workers need to survive the epidemic (see Table 1):

The Large Employer Exclusion (1.9 million North Carolina workers left out).

Most importantly, the Trump Administration demanded (and received) a blanket exemption for every business with more than 500 employees, arguing that most of these large employers already had paid sick policies covering their workers and didn’t need a new federal program interfering with policies already had in place. In practice, however, most of the frontline workers for these large employers—the warehouse employees at big-box retailers, the food preparers at Taco Bell, the line workers in Smithfield pork processing plants, the truckers and construction workers—never had paid sick days to begin with (see Section 3). So while some employees working for the nation’s biggest businesses have some kind of paid sick leave, most do not. As a result, the large employer exclusion means they won’t get paid sick days when they need it most. As seen in Table 1, the large employer exemption leaves 1.9 million workers without guaranteed access to paid sick leave.

The Healthcare/First responder Exemption (191,430 North Carolina workers left out).

In a second exclusion, Families First exempts all private healthcare workers and first responders—another 191,430 workers left out—with the argument that these workers are too essential to allow to take time off, even if sick with the very virus they’re trying to fight in their patients. Although many doctors and nurses already have paid time off, other lower-paid frontline healthcare workers like med techs, medical assistants, and orderlies do not, forcing thousands of these vital healthcare workers to choose between their paycheck, getting well, and potentially infecting their colleagues and their patients.

The Small Business Hardship Waiver (a maximum of 884,383 North Carolina workers left out).

Lastly, Families First allows small businesses of fewer than 50 employees to apply to the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL) for a hardship waiver exempting them from the paid sick days provisions, under the Trump Administration’s theory that many small businesses are too small to allow their employees to leave work, even if they’re sick. But this theory makes little sense in practice—the smaller the business, the fewer the employees, and the greater the risk that sick workers can knock out the entire staff of that business if they come in sick. It’s true that many small businesses will choose to offer the emergency sick leave to protect their employees and customers, especially given the fact that the federal government will cover the cost of the leave. But if every small employer in the state did seek a waiver, it would exempt as many as 884,383 workers from access to guaranteed paid sick days.

Taken together, these various provisions only guarantee paid sick days access to public sector workers and those private sector employees working for businesses with between 50 and 499 employees. As a result, these loopholes could leave anywhere from 2.1 million to 3 million North Carolina workers without access to paid sick days just as the COVID-19 crisis peaks. That’s as much as 83 percent of the state’s workforce—a huge hole in the protections workers need.

U.S. Department of Labor guidelines exempt millions more

Unfortunately, the USDOL took these loopholes and made them even bigger. In new rules issued on April 1 as part of implementing the emergency paid sick days program, USDOL granted additional exceptions significantly beyond those granted to employers in the Families First Act4 —in effect, ensuring that even fewer workers would have access to guaranteed paid sick days in the middle of the epidemic. These include:

- MORE HEALTHCARE WORKERS EXEMPTED. The new rules expanded the healthcare exemption to include any industry in the healthcare supply chain.5 As a result, many kinds of companies manufacturing everything from drugs to medical devices and protective gear won’t be required to provide their workers with emergency paid sick days.

- ALL “ESSENTIAL” WORKERS EXEMPTED. Most importantly, the new rules specifically exempt “essential workers,” as defined by a state’s governor.6 In North Carolina, Governor Roy Cooper has designated a wide range of industries as essential, including every industry identified by the U.S. Cyber Infrastructure Administration as “critical”7—which includes almost 70 percent of the American economy.8 Even more troubling, individual employers are given the discretion to decide whether or not they are “essential” within these broad definitions. In practice, this means that many employers will claim they are essential as a way to avoid shutting down operations or giving their workers time off. As a result, millions of workers who otherwise could access federal paid sick days through Families First will now have none—and face the life-threatening choice of coming to work sick or staying home and losing their paycheck.

Taken together, these two new exemptions alone could exclude as many as 3.1 million North Carolina workers from paid sick days coverage9—everyone from workers in chemical manufacturing facilities to Dollar Store workers to farmworkers. Due to data limitations, we don’t know how many of these essential workers were already left out due to the original exclusions in Families First, but it’s clear that the new USDOL rules have significantly reduced the number of workers who would have otherwise received access to paid sick days.

Women and workers of color disproportionately lack paid sick days as they bear the brunt of COVID-19 deaths

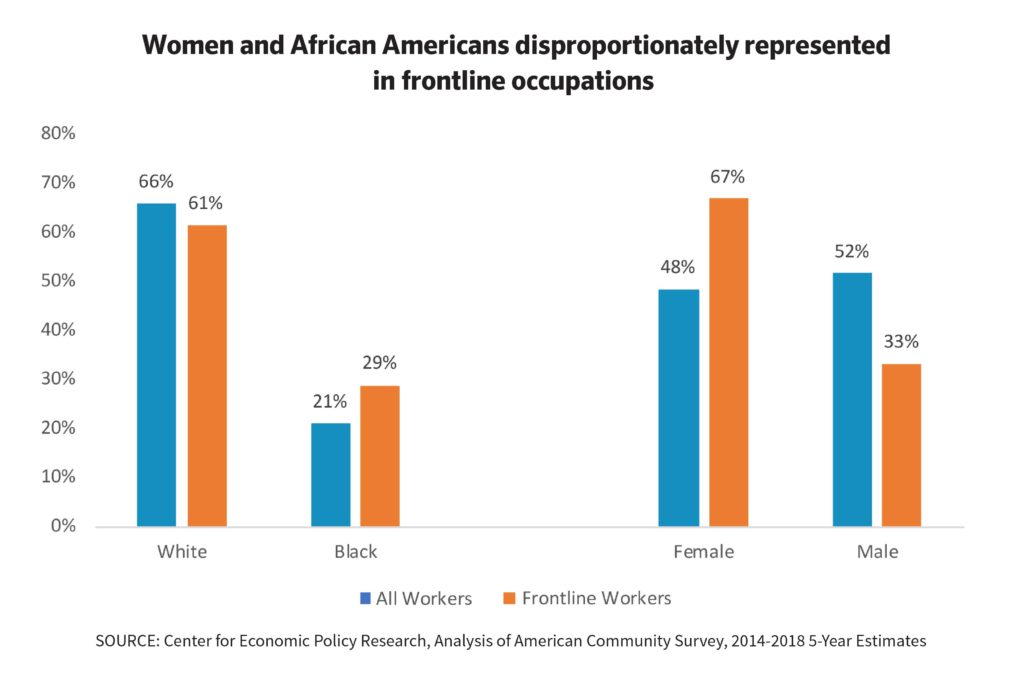

Across the country, women and people of color—especially those in the Black community—are becoming infected and dying from COVID-10 at exceptionally higher rates than the national average.10 At the same time, these workers disproportionately lack paid sick days compared to the broader workforce, largely because they are overly concentrated in frontline occupations that have been deemed “essential” in combatting the epidemic and are thus excluded from federal paid sick days protections. Many of those occupations lacked paid sick days prior to the crisis as well, leaving whole swaths of the workforce—especially women and workers of color—uniquely vulnerable to COVID-19, absent any federal protections.

As seen in Table 2, Black workers represent 21 percent of the overall workforce but almost 30 percent of the frontline workforce, compared to their white counterparts who represent 66 percent of all workers but just 60 percent of frontline employees. Similarly, more than two-thirds of frontline workers are women, despite making up only half of the total workforce. Due to historically rooted patterns of occupational segregation and discrimination, the burden of frontline work falls squarely on communities of color.

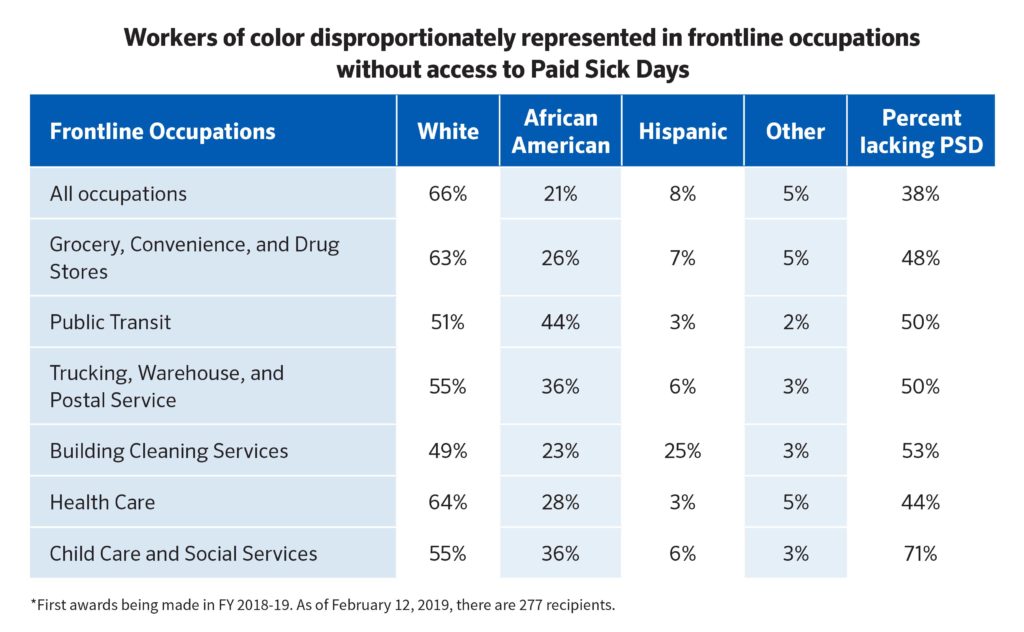

So, who are these frontline workers and what kinds of work do they do? As seen in Table 3, they work in grocery stores and drug stores, drive buses and clean facilities, pack boxes in Amazon warehouses and transport those boxes in trucks, provide direct healthcare services to sick patients—everything from doctors to nurses to med techs and assistants—and take care of other frontline workers’ children in daycare centers.11

All of these occupations are critical in the fight against COVID-19, and in all of them, people of color—especially Black workers—are punching above their weight in frontline occupations when compared to their numbers in the workforce as a whole (see Table 3). Looking across the entire economy, Black workers make up about 21 percent all workers. Yet they represent 44 percent of all public transit workers, 36 percent of all trucking and warehouse employees, 36 percent of all childcare workers, and 28 percent of healthcare workers. Similarly, Latino workers make up only 8 percent of the workforce, yet they represent 25 percent of all building cleaning services. They also make up the overwhelming majority of our nation’s farmworkers, growing and processing the food we all eat, and are and the work they do is clearly essential to our country’s survival.12

Unfortunately, too many workers in these occupations lacked basic access to paid sick days even before COVID-19 began, making their exclusion from federal protections even more damaging. While 38 percent of all workers across the economy lacked paid sick days at the beginning of the crisis, many more workers in frontline occupations already lacked access—ranging from 44 percent without paid sick days among healthcare workers to a stunning 71 percent of childcare workers. Because workers of color are overrepresented in these occupations, they are also disproportionately suffering from lack of paid sick days.13

In other words, thousands of frontline workers—mostly people of color and women of all races—do not receive paid sick days from their employer. Now, thanks to the U.S. Department of Labor’s new rules, they are also excluded from the federal paid sick days program, effectively leaving them exposed to the ravages of the coronavirus and forcing them to choose between their paycheck and their health.

Policy Recommendations

Working people should not have to choose between their health, the health of their coworkers and loved ones, and their paycheck in the middle of a pandemic that’s infecting hundreds of thousands of people across the country. Instead, policy makers at both the state and federal levels should take the following actions to ensure that every working person in North Carolina and the country at large has access to paid sick days protections to keep them alive and healthy on the jobs:

- Congress needs to end all of the exclusions and exemptions contained in the Families First Act and USDOL rules. No worker should lack access to paid sick days based on the size or industry of their employer. Congress should take the opportunity provided in the soon-to-be-developed COVID-4 package to close these loopholes.

- Absent a federal fix, the North Carolina General Assembly should act on its own to eliminate all of these exclusions, including those related to large employers, small employers, healthcare, frontline, and essential industries. Such action would require that all private-sector employers provide 80 hours of paid sick time to both full- and part-time workers at 100 percent of their wages.

- The General Assembly should enact the KinCare Act (H899), which would guarantee all North Carolina workers the right to use their sick days (whether paid or job-protected, unpaid) to care for a sick loved one, seek preventative care, or deal with the physical, mental, or legal impacts of domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking. This bill unanimously passed committee with bipartisan support in 2019.

Footnotes

- Sirota, Alexandra et al. (2016) State of Working North Carolina 2016: See A Better Balance, Summary of Studies on the Health Effects of Paid Safe and Sick Time Ordinances (2019), https://

www.abetterbalance.org/resources/summary-of-studies-onthe-health-effects-of-paid-sick-safe-timeordinances/ - People without access to paid sick leave are 1.5x more likely to go to work while they have a contagious illness and are nearly twice as likely to send a sick child to school or daycare than those with access to it. Tom W. Smith & Jibum Kim, Paid Sick Days: Attitudes and Experiences, Nat’l Opinion Res. Ctr. at U. of Chi. (June 2010), https://www.issuelab.org/resource/paid-sick-days-attitudesand-experiences.html.

- US Department of Labor. (2020). Families First Coronavirus

Response Act: Employee Paid Leave Rights. Accessed online at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/pandemic/ffcra-employeepaid-

leave - U.S. Department of Labor. (2020). Paid Leave Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act: A Rule By the Wage & Hour Division. The Federal Register. 85 FR 19326. pp. 19326-19357. Accessed online at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/04/06/2020-07237/paid-leave-under-thefamilies-first-coronavirus-response-act

- Ibid

- Ibid

- State of North Carolina. (2020). Executive Order: Stay at Home Order and Strategic Directions for North Carolina in Response to Increasing COVID-19 Cases. EO 121, March 27, 2020. Accessed

online at https://files.nc.gov/governor/documents/files/EO121-Stay-at-Home-Order-3.pdf. Also see Cyber Infrastructure Security Administration, Critical Infrastructure Sectors. https://www.cisa.gov/critical-infrastructure-sectors - NCJC analysis of employment for CSIA designated industries

- Analysis by the Budget & Tax Center (unpublished)

- Gupta, Sujata. (2020). “Why African-Americans may be especially vulnerable to COVID-19: African-Americans are more likely to die from the disease than white Americans.” Science News. April 10, 2020. Accessed online at https://www.sciencenews.org/article/coronavirus-why-african-americans-vulnerable-covid-19-health-race

- These occupations are specifically identified in a preliminary and unpublished analysis by the Center for Economic and Policy

Research, and it should not be considered exhaustive. It is likely that future analysis of frontline workers will reveal additional occupations that should also be included. - See note 11. Agricultural workers are not included in CEPR’s definition of “frontline” workers, so they are not included in the occupational analysis. Nonetheless, they are considered essential under recent executive orders.

- Institute for Women’s Policy Research analysis of 2015-2017 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and 2017 IPUMS American Community Survey (ACS).

Justice Circle

Justice Circle