The North Carolina state budget has real and meaningful impacts on our daily lives. From education and health care to transportation and small business loans, state and local budgets provide the resources that families and businesses need — especially in times of crisis. The COVID-19 outbreak and resulting economic fallout have intensified the need for public programs and additional revenue. Unless we act, the state will not collect enough revenue to ensure that everyone has access to the public services they need to thrive.

The COVID-19 pandemic is putting substantial pressure on North Carolina’s state budget. First, the increased demand for public programs has created an explosion in need for existing services and a host of unforeseen costs. Second, tax revenues have contracted as the public health crisis has stalled the economy. The dual impact of a shrinking tax base and a growing need for public services is contributing to state and local budget shortfalls. The magnitude and duration of the budget crisis is still unknown. Early economic indicators suggest that the impact on state finances will be severe. Unless North Carolina raises revenue from those most able to pay, thousands of people could lose access to the public services and supports they need to emerge resilient from this crisis.

The unprecedented nature of the coronavirus pandemic makes it difficult to compare to previous recessions. Unlike 2001 and 2007, the current economic fallout was not caused by a dip in demand but by a public health emergency that required restrictions on the movement of people. Although necessary to ensure the health of our people and economy, stay-at-home orders have brought consumption and production to a screeching halt for most businesses.[1] As a result, North Carolina has seen a record number of unemployment claims — more than 1 million since the State of Emergency began.[2]

Due to the rapid decline in economic activity, state fiscal projections do not yet fully account for revenues that already have fallen, much less account for future shortfalls. No official state projections have been released for North Carolina,[3] but the following estimates suggest the degree to which state revenues and budgets will be impacted by COVID-19.

Preliminary estimates of the fiscal impact of COVID-19

Given the rapidly developing economic downturn and unique nature of this crisis, it is not surprising that there are differences between the financial estimates that have been released to date, but they all suggest that more federal aid and state revenue will be needed to balance the budget.

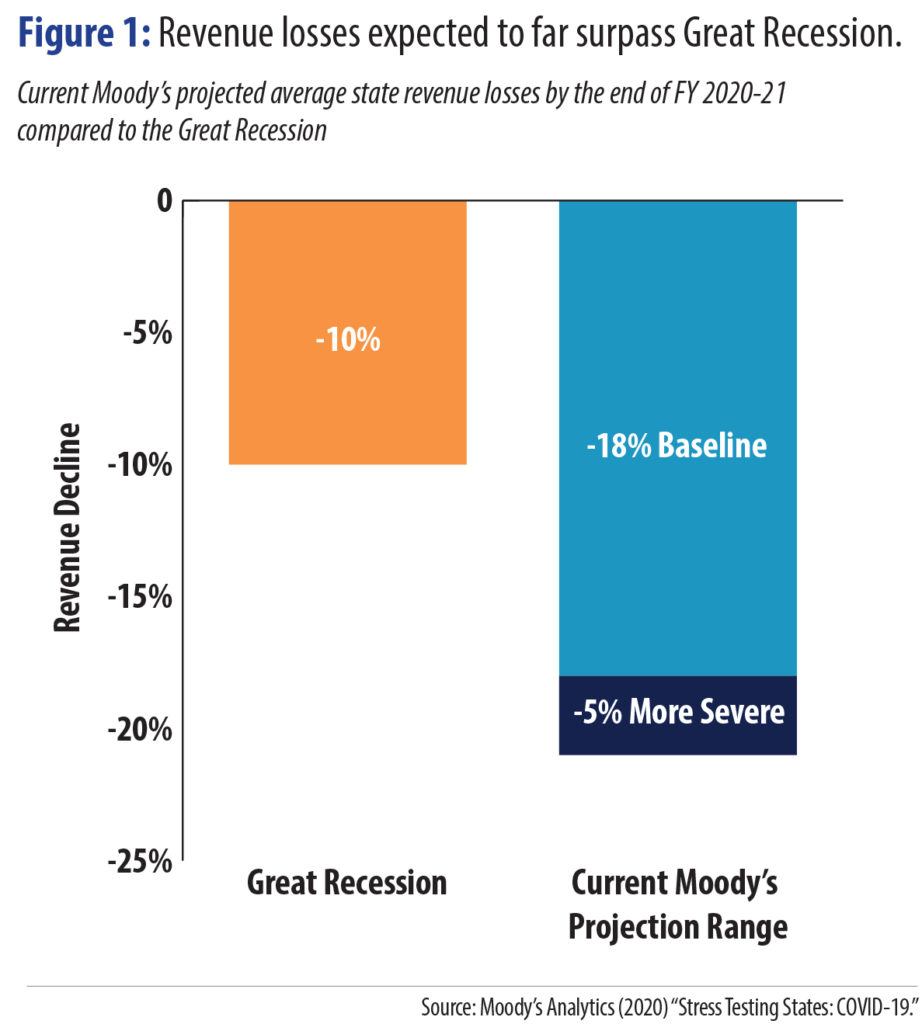

Moody’s Analytics estimates North Carolina’s tax revenue shortfall will be between 10.1 percent and 13.3 percent, or between $2.5 billion and $3.3 billion, this fiscal year.[4] Even conservative estimates anticipate that North Carolina’s revenue loss will be more severe than it was during the Great Recession.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that on average, state revenues will decline by about 10 percent this fiscal year[5] and could fall by as much as 25 percent in the next fiscal year,[6] which begins on July 1, 2020.[7] This means that under a severe scenario — where unemployment continues to rise and GDP declines dramatically — North Carolina could see revenue decline by more than $6 billion in the next fiscal year.

Congressional action has provided North Carolina with more than $6 billion in federal aid.[8] However, the U.S. Treasury has placed onerous restrictions on the approximately $4 billion flowing to North Carolina through the Coronavirus Relief Fund, which must be used to pay for costs incurred due to the public health emergency.[9] Unless more flexibility is allowed or additional funds are allocated specifically for state fiscal relief, federal funds may not be used to make up for lost revenue. Therefore, state funds, including new revenue, will be needed to cover budget shortfalls while meeting the demand for public services.

Decreasing revenues and growing need for public services

State and local budget shortfalls, no matter the magnitude, will occur as a result of decreasing revenues and elevated demand for public services in response to the economic impact of COVID-19. Preliminary estimates from Moody’s Analytics project a potential budget shortfall (revenue plus expenditures) of $3 billion to $4 billion,[10] but the actual financial hole could be even larger. Current projections are based on economic forecasts, and as the economic consequences of COVID-19 expand, revenues will continue to decline.

Revenue declines account for the majority of the fiscal stress that the state should anticipate. Revenues fall during every recession, but the unprecedented loss of jobs and income as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak suggests that the current economic collapse threatens to impact tax and fee collections by an even greater degree than during the Great Recession.

At the same time as our existing funding streams decline, there is a growing need for public services. Increased demand will come in many forms, some easy to anticipate and others harder to predict. Some of the most important public investments in response to COVID-19 are:

- Existing public programs: There will be increased demand for existing programs like Medicaid, food assistance, housing, and child care as families across the state cope with the immediate impacts of the outbreak.

- Administrative infrastructure: State agencies must increase their staffing and infrastructure to deliver essential emergency services. The Department of Employment Security has already tripled its staff to keep up with the unprecedented wave of Unemployment Insurance claims.[11] Agencies will need more resources to build the infrastructure required to meet demand.

- Emergency and recovery interventions: Families and communities need unique forms of support to respond to immediate threats and recover more resiliently. The Economic Impact Payments received by many people are a good start, but not everyone will receive them, and they won’t be enough to replace lost income.

Taken together, the elevated need for emergency response and long-term economic recovery will further widen the gap between what the state needs to provide and what comes in through the current revenue system.

North Carolina is not yet prepared to deal with the combined impact of declining revenues and increased need for public services. State leaders must identify ways to draw down additional federal funds, maximize existing state dollars, and raise new revenues without putting additional burdens on the people most impacted by COVID-19. Failure to do so will cause people to lose access to services precisely when they are needed the most, creating a longer, more painful, and less equitable recovery.

Impact on local governments

Local governments — cities, towns, counties, and tribal governments — are on the frontlines of responding to COVID-19 and need adequate revenue now to continue delivering vital services like education, health, and safety. The public health emergency and economic collapse has required local governments to rapidly increase capacity at a time when revenues are declining (particularly sales taxes, permits, and fees). Federal aid was directed to only three of the state’s most populous counties,[12] leaving most cities, towns, and counties without aid. The first phase of legislation from the N.C. General Assembly in response to COVID-19 did provide resources to all counties, but more assistance will be needed to respond to growing needs and make up for lost revenue. Because local governments are limited in the ways that they can raise revenue, the best way to address local budget shortfalls is for the federal and state governments to provide additional fiscal relief.

Addressing shortfalls without cutting vital services

Unlike the federal government, North Carolina cannot spend more than it collects in revenue. If state lawmakers cut vital services to balance the budget, there will be painful consequences, especially for communities that have experienced decades of underinvestment that often has masqueraded as fiscal restraint.

North Carolina currently has over $1 billion in its Savings Reserve Account (often called the Rainy Day Fund) and even more in its unreserved balance, which includes funds that were left unallocated after failing to pass a comprehensive state budget.[13] That means the state has billions of dollars that can be used to plug budget gaps.

While North Carolina has significant resources waiting to be deployed, existing funds will not close the gap created by declining revenues and increasing needs. Completely exhausting the Rainy Day Fund would leave at least a $2 billion to $3 billion shortfall while eliminating our capacity to respond with hurricane Season on the horizon. Even if North Carolina spends down its total balance (Rainy Day Fund plus unappropriated funds), the state budget shortfall could still reach more than a billion dollars.[14]

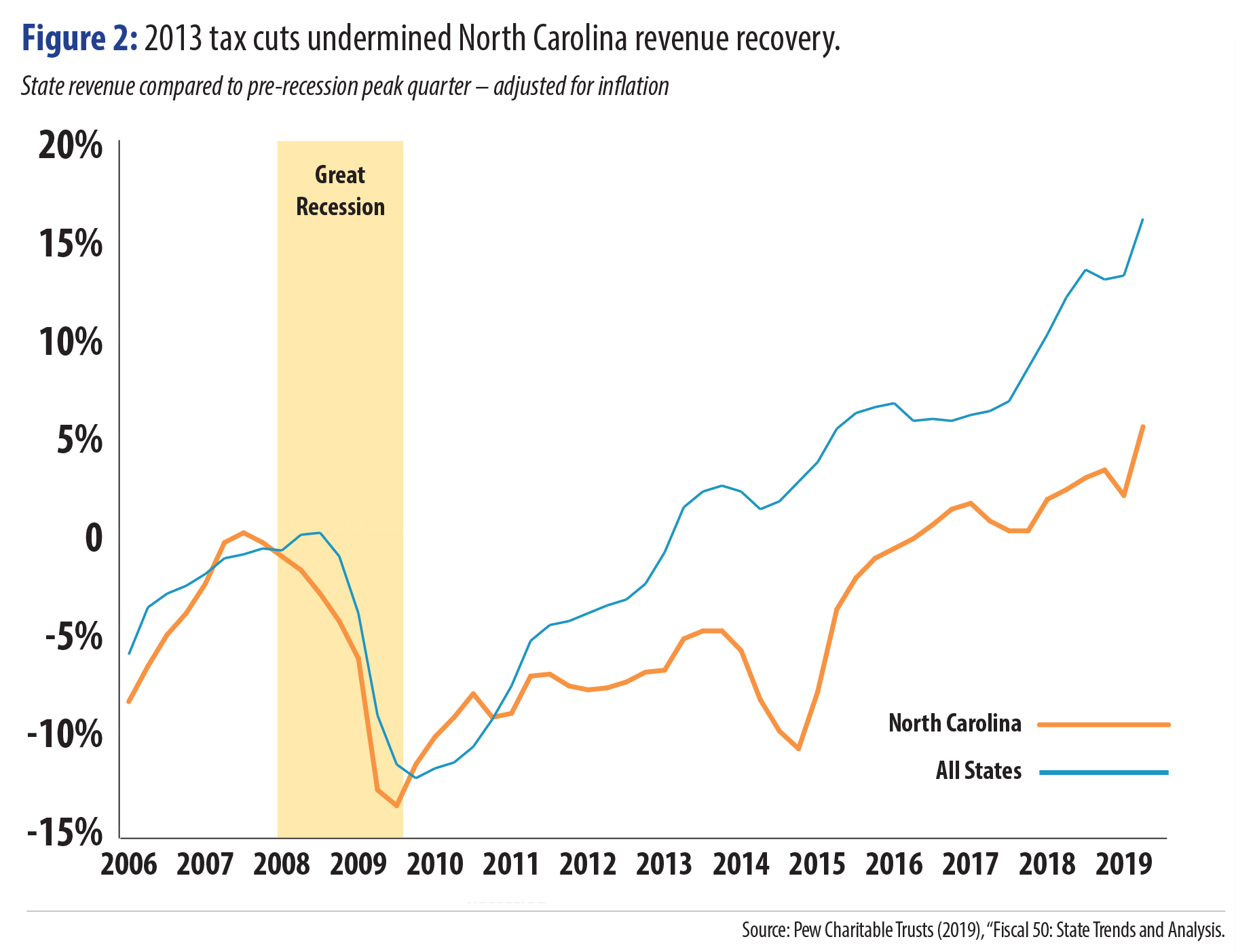

Confronted with this stark reality, the state will need to raise revenue to avoid cutting vital services. Revenue-raising proposals should aim to restore fairness to the tax code by asking those who make the most to pay the most. The top 20 percent of North Carolinians earn more income than everyone else combined.[15] North Carolina’s current upside-down tax code exacerbates inequities, especially in times of crisis. In 2013 the state flattened and capped income tax rates while setting off a cascade of declining corporate tax rates for big businesses (the lowest in the region). As a result, North Carolina loses out on more than $3.6 billion in revenue each year had the tax rates remained at 2013 levels.[16] If tax cuts for the wealthy were reversed, the state could cover most, if not all, of the revenue shortfall that is anticipated this year without even touching its savings or reserves.

Conclusion

Inequitable access to health care, safe housing, and economic opportunities have made North Carolina less resilient in the face of COVID-19. Policymakers should value people over profits and recognize that healthy communities are a prerequisite to a healthy economy, especially now. Without enough federal funds to cover the costs of responding to the pandemic, North Carolina should anticipate significant budget shortfalls in the coming years. The larger the shortfall, the more important it is to raise revenue by asking the wealthiest among us to contribute their fair share to our collective well-being.

[1] Lowry, Annie. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/quantifying-coming-recession/608443/

[2] COVID-19 and the Labor Market. https://www.ncjustice.org/projects/budget-and-tax-center/economy/labor-market-in-n-c/

[3] Except from an email on March 30 from legislative economist Barry Boardman indicating that revenue could be down $1.5B to $2.5B during the biennium. https://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/article241825946.html

[4] Moody’s Analytics. FY 2019-2020. https://www.economy.com/economicview/analysis/379097/StressTesting-States-COVID19.

[5] FY 2019-2020

[6] FY 2020-2021

[7] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-start-grappling-with-hit-to-tax-collections

[8] Khachaturyan, Suzy. https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/btc-fact-sheet-federal-funding-for-north-carolina-covid-19-response-is-a-good-start-but-much-more-support-is-needed/

[9] United States Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Coronavirus-Relief-Fund-Guidance-for-State-Territorial-Local-and-Tribal-Governments.pdf

[10] Moody’s Analytics. (2020). Stress Testing States: COVID-19.

[11] North Carolina Department of Commerce. https://des.nc.gov/news/press-releases/2020/04/17/des-triple-staff-meet-unprecedented-surge-unemployment-claims.

[12] Khachaturyan, Suzy & Pedersen, Leila. https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/nc-general-assembly-should-use-federal-dollars-to-build-an-equitable-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic/

[13] State of North Carolina. Office of the State Controller. https://files.nc.gov/ncosc/documents/files/GFMR/2020/March_2020_Gen_Fund_Monthly_Report.pdf.

[14] Moody’s Analytics. https://www.economy.com/economicview/analysis/379097/StressTesting-States-COVID19.

[15] McHugh, Patrick. https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/top-20-took-home-51-of-all-income-in-2018-in-n-c/

[16] McHugh, Patrick. https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/north-carolinas-tax-cuts-failed-to-boost-economic-growth/

Justice Circle

Justice Circle