All graduates of North Carolina’s high schools should have the opportunity to continue their education, either at a four-year or two-year institution, so they can gain the credentials or degree that will boost their careers and help modernize the state’s economy. But for students who are undocumented immigrants — many brought to the U.S. at a very young age — the financial barriers are often too steep to scale. North Carolina requires them to pay expensive out-of-state tuition, which can be an insurmountable cost for low- and moderate-income families, and there is no access to federal financial aid for these graduates.

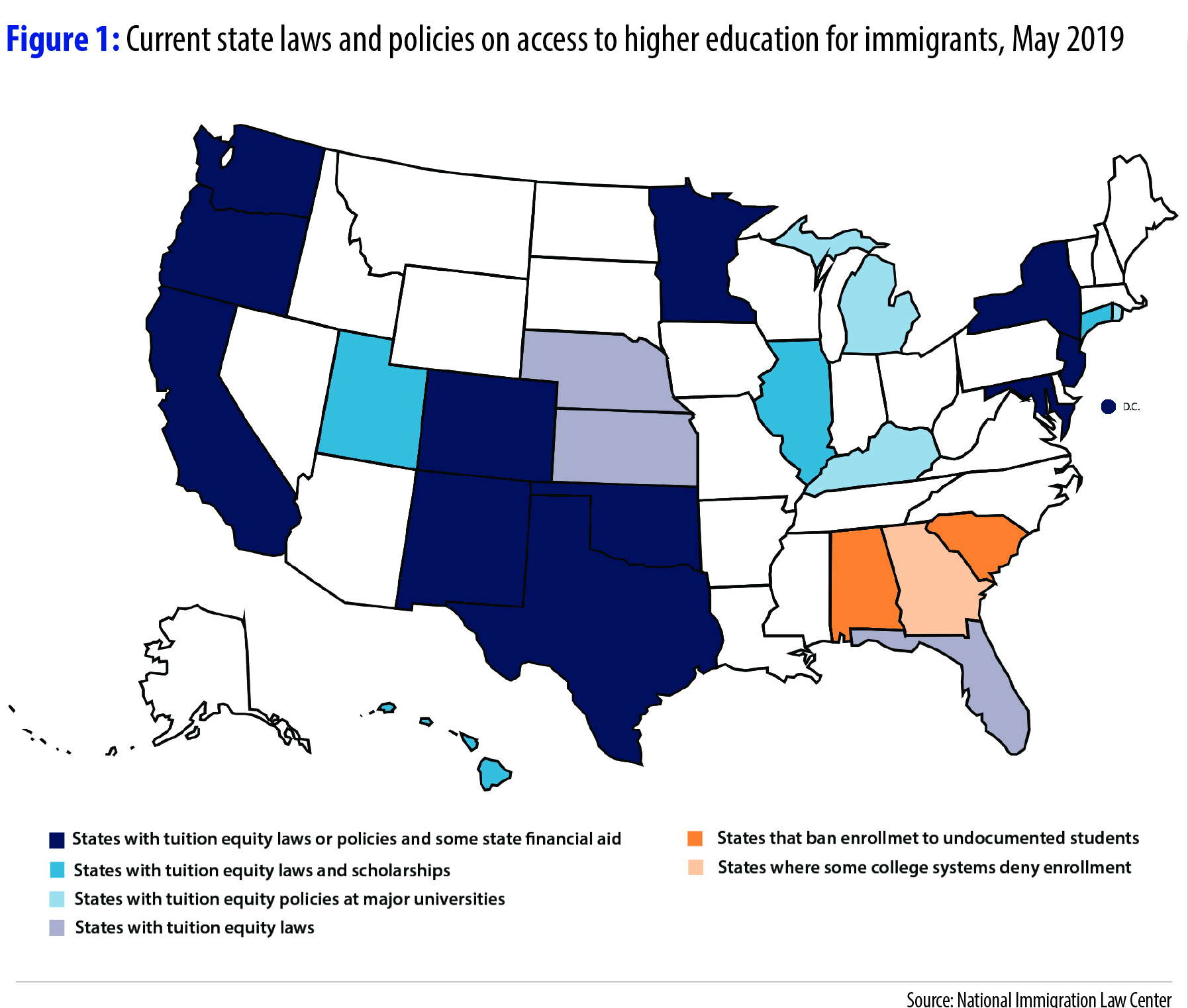

Twenty-one states across the country have implemented a promising policy that allows graduates of in-state high schools who are undocumented to pay the more affordable in-state tuition at public universities or community colleges. Such “tuition equity” has boosted college enrollment, furthered the education of young immigrants, and improved their earnings1 — all of which can only help boost a state’s economy in the long run.

Given the priority North Carolina has placed on increasing the number of people who have credentials and degrees through the myFutureNC Commission — a collaboration between leaders in the education, business, and governmental sectors to increase post- secondary attainment by 2 million people by 20302 and legislative efforts to require annual progress reports3 — it is clearly counterproductive to our stated goals to maintain this barrier to post-secondary education. Tuition equity is a cost-effective way to make sure North Carolina isn’t left behind.

Removing barriers to education for young immigrants would boost the economy

Furthering the education of young immigrants would improve the quality of North Carolina’s labor force and make the state more attractive to businesses. By 2020, nearly 61 percent of jobs in North Carolina will require some post-secondary education, according to projections by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.4 Investing in higher education can pay big returns, such as a more stable workforce with better opportunities to move into the middle class and beyond.5

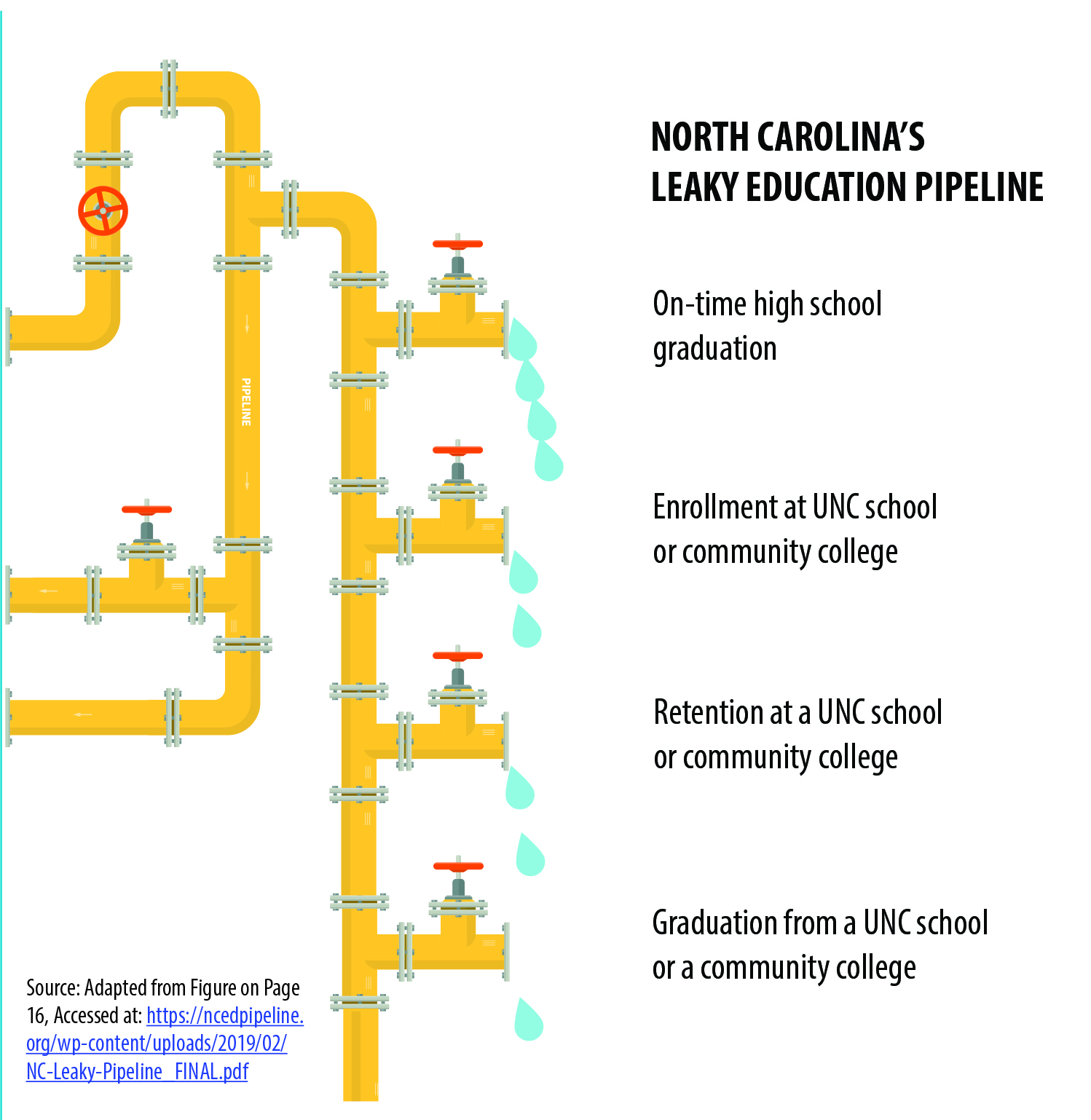

North Carolina leaders have set a goal of increasing the educational attainment levels of those aged 25 to 44 years — 2 million more North Carolinians, or nearly two-thirds of the North Carolinians in that age group—will have a credential or degree that can deliver higher earnings and a boost to the broader community and economy.6 This goal has come as many researchers have documented the “leaky education pipeline” in North Carolina, which is characterized by people stopping and leaving educational programs at various points along the continuum of educational opportunities. Notably, these decisions to leave educational programs are resulting primarily from the barriers to completion that are not addressed through policies or adequate funding of services. Of particular note by researchers is the importance of post-secondary enrollment and continuous enrollment to rates of completion and achieving this goal of increasing educational attainment.

Repairing the leaks in the education pipeline will benefit us all. States with large numbers of bachelor’s degree holders have higher median wage levels than other states, according to the Economic Policy Institute.7 An advanced education also helps make workers more upwardly mobile. In North Carolina: The median annual wage for someone with a bachelor’s degree is $24,689 higher than for someone with only a high school diploma.8

Tuition equity is just one policy that can support the shared goal of increasing attainment for all. Access to financial aid would go even further to support the attainment goals of these young people educated in the K-12 system in North Carolina.9

As would funding formula changes that would support the educational attainment of English Language Learners in the K-12 system.10

Moreover, policies that support continuous enrollment of all students would provide benefit to those who have low-incomes and limited supports in their educational pursuits. These policies include removing limits on access to child care supports while enrolled in post-secondary education, increasing access to food assistance on campuses, investing in affordable housing, and building connections to careers and employers while still enrolled in post-secondary institutions.11

Students who are undocumented face particularly high obstacles, including low education levels among their parents, low family incomes, and lack of information about the post-secondary education process and the requirements. Moreover, undocumented students face higher costs because they have to pay out-of- state tuition rates and have limited access to financial aid and other programs that would help further their education.12

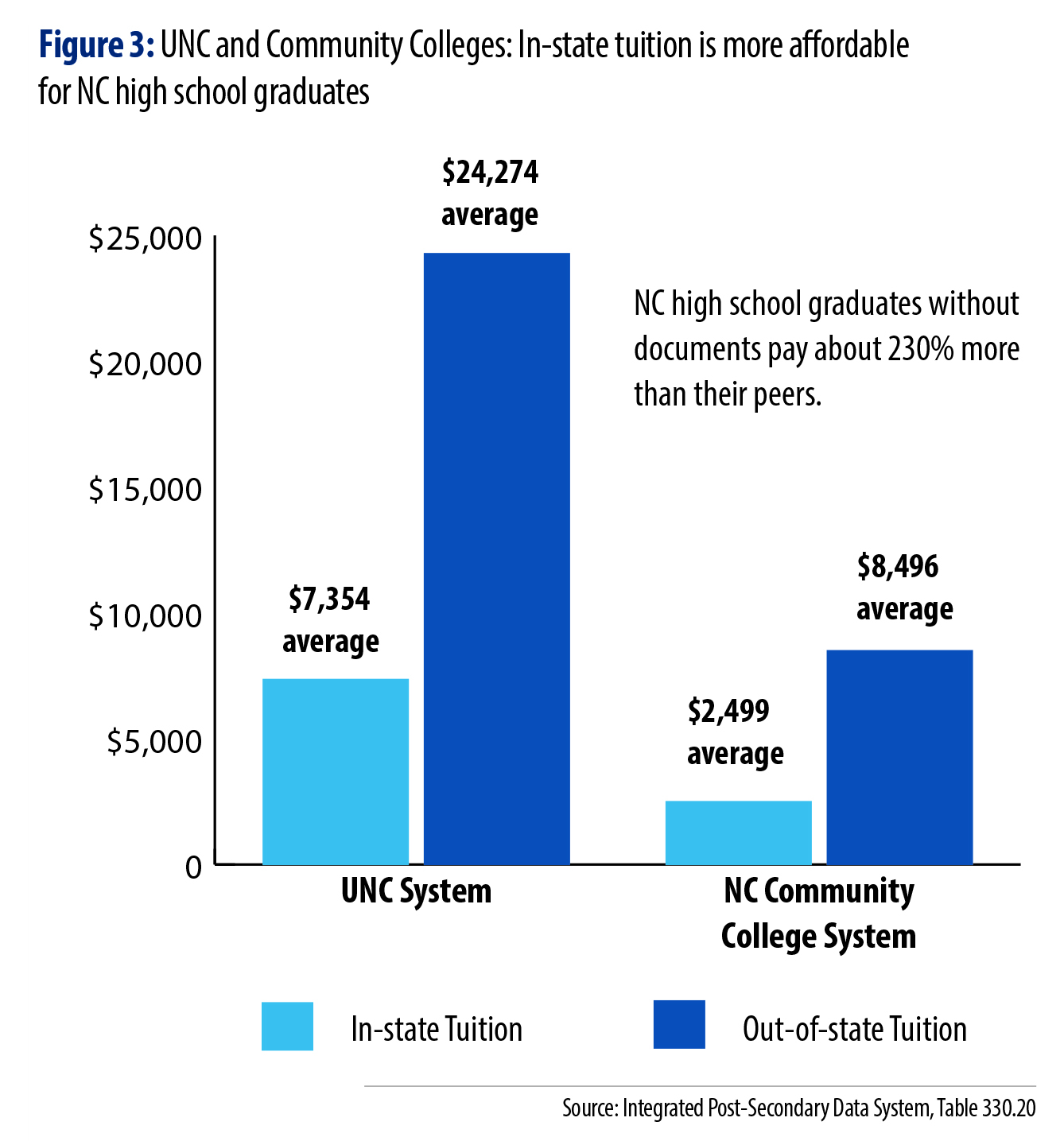

As Figure 3 shows, graduates of North Carolina high schools without immigration documents would have to pay at least 230 percent more in required tuition and fees than their graduating classmates.

Removing these barriers for young immigrants living in North Carolina can improve their earnings, increase economic mobility across generations, and help meet industry’s demand for well-educated, skilled workers.

How tuition equity works

Tuition equity allows undocumented students who have been educated in a state’s K-12 schools to pay in-state tuition at public colleges or universities in that state. By law, all students must have access to public K-12 education regardless of their immigration status.13 In some states, undocumented students can qualify for in-state tuition only if they have attended a public grade or high school in that state for at least three years. Some states have lowered barriers to higher education by providing undocumented students with access to state financial aid, since they are prohibited from receiving federal financial aid for higher education.14

A tuition equity policy in North Carolina could benefit roughly 1,470 students each year.

15 This is based on new data from the Migration Policy Institute on the annual number of graduates in each state without documents.16 In that analysis, North Carolina ranks fifth, tied with Georgia, for the number of graduates from our state’s high schools who do not have documented immigration status. Those 3,000 young people in North Carolina represent roughly 3 percent of the total undocumented youths graduating each year nationwide. 17

The number who would enroll even with tuition equity is likely much lower than this estimate. The last available estimate from 2009 for the community college system suggested that North Carolina had just 111 undocumented students enrolled in community colleges,18 which can be attributed at least in part to the prohibitive cost and the perception that North Carolina does not have an open door when it comes to post-secondary education.

Tuition equity has the potential to substantially improve educational and economic opportunities for young people in North Carolina. In states that have adopted an in-state tuition policy for those students without documents, there has been a 31 percent increase in college enrollment for undocumented students and a 33 percent increase in the proportion of Mexican young adults with a college degree.19

Fiscal costs and crowd-out concerns are overblown

Opponents of improving access to higher education for all students who graduate from North Carolina high schools cite the potential cost to the state and the concern that undocumented students will take college classroom seats away from native-born students. But neither concern is credible.

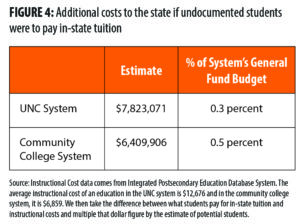

Looking solely at the cost of allowing these students to pay in-state tuition — and not accounting for economic benefits such as the higher earnings of undocumented college graduates — the cost to the state is likely to be minimal.

Assuming this small number of undocumented students enrolled in either the UNC system or the community college system and factoring in the average instructional costs of an education at the UNC system or community colleges, the additional costs to the state would be approximately 0.3 percent of the UNC system budget or 0.5 percent of the community college system budget. The table in Figure 4 illustrates these findings.

Despite the potential for a slight increase in costs, other states have seen either increases in revenue from higher enrollment or have estimated other positive economic benefits from tuition equity that offset the costs. In Texas, the Higher Education Coordinating Board reports that tuition and fees paid by undocumented immigrants were greater than the cost to the state of their instruction.20 California also found that expanding the number of students who are allowed to pursue post-secondary education increased the total school revenues.21 In Maryland, analysis of the tuition equity policy for community colleges found a projected increase in revenue for the state and net positive economic benefits for local communities.22 Families will also reap benefits directly through lower tuition bills, leaving them with more money to spend on other needs or to save for emergencies. Over the long term, tuition equity has the potential to increase state revenue collections through increased spending and earnings by a larger number of college graduates, thereby offsetting costs.

North Carolina is already obligated to invest in educating undocumented students in K-12 schools.23 By making it harder for these students to pursue a college education, the state is losing much of the value of that initial investment.

Opponents of tuition equity have claimed that increasing the number of undocumented university and college students will mean less room for native-born students. There are several reasons that this is unlikely to be true in North Carolina. First and foremost, the number of undocumented students likely to enroll is negligible relative to the native-born student population, particularly given that enrollment would occur across 16 UNC campuses and 52 community colleges. Even if every single estimated undocumented student enrolled in college, they would represent less than 1 percent of the total in-state students in the public post- secondary systems.

Second, enrollment at both community colleges and the UNC System has been declining. Finally, researchers have looked at the states that have implemented tuition equity as well as previous reforms and found no harm to native-born students from increased enrollment of undocumented students. In one study, researchers actually found that more American-born Latino students attended post-secondary schools, likely as a result of the positive effect of their undocumented classmates increasing their college-going rate.24

Tuition equity is an important tool for furthering the state’s goal of advancing the education of its residents and ensuring that the workforce is ready for the jobs of the future. By lowering the cost barrier to college for undocumented students, North Carolina will come out ahead—with minimal costs and strong economic benefits.

Footnotes

- National Immigration Law Center, Background on In-State Tuition Policy and Appendix of State Reports, Accessed at: https:// www.nilc.org/issues/education/eduaccesstoolkit/

- More information about MyFutureNC can be found at: https://www.myfuturenc.org/about/

- House Bill 664, NC General Assembly, Accessed at: https://www.ncleg.gov/Sessions/2019/Bills/House/PDF/H664v3.pdf

- Carnevale, Anthony P. and Nicole Smith, July 2012. A Decade Behind: Breaking out of the low-skill trap in the southern economy. Center on Education and the Workforce: Georgetown University, Washington DC.

- Carnevale and Smith, 2012.

- The Steering Committee of the MyFutureNC Commission, A Call to Action for the State of North Carolina. Accessed at: https://www. myfuturenc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/A-Call-to-Action-Final-Report_040319.pdf

- Berger, Noah and Peter Fisher, August A Well Educated Workforce is Key to State Prosperity. Economic Policy Institute: Washington, D.C.

- Economic Policy Institute, Analysis of Current Population Survey,2018.

- https://ncedpipeline.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/NC-Leaky-Pipeline_FINAL.pdf

- Sirota, Alexandra, August Funding the Educational Success of All Learners. Accessed at: https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/funding- the-educational-success-of-all-learners/

- Duke-Benfield, Mary Ellen, Rosa Garcia, Lauren Walizer and Carrie Welton, September 2018. Developing State Policy that Supports Low- Income, Working Accessed at: https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2018/09/2018developingstatepolicythatsupp ortsstudents.pdf and Jobs for the Future, Smart Postsecondary Policies that work for Students and the Economy. Accessed at: https://jfforg- prod-prime.s3.amazonaws.com/media/documents/Full_Postsecondary_Smart_Policies.pdf

- Baum, Sandy and Stella Flores, Spring 2011. Higher Education and Children in Immigrant Families. Future of Children, Vol. 21, No. 1. Princeton University: Princeton, NJ.

- Plyler Doe, 1982

- These states include California, Hawaii, New York, Texas and Washington.

- Author’s calculation using the Migration Policy Institute estimate of annual high school graduates who don’t have documented status and applying the national rate of attendance at post-secondary institutions of undocumented The methodology is adapted from the Colorado Fiscal Institute method detailed in A Sizeable Return on Investment: Costs and Benefits of Colorado’s Asset Bill. February 2011.

- https://www.migrationpolicorg/research/unauthorized-immigrants-graduate-us-high-schools

- Guerrero, Lissette, May 10, HB 319 would create needed tuition equity for immigrant youth. Progressive Pulse NC, Accessed at: http:// pulse.ncpolicywatch.org/2019/05/10/hb-319-would-create-needed-tuition-equity-for-immigrant-youth/

- JBL Associates, Study on the Admission of Undocumented Students into the NC Community College System. Accessed at: http://digital. ncdcr.gov/cdm/ref/collection/p249901coll22/id/635737. Estimates are not available on the number of undocumented students in the UNC System.

- http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pam.20366/abstract

- Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, October Overview: Eligibility for In-state Tuition and State Financial Aid found the net gain for the state to be $11.07 million.

- Institute for the Study of Societal Issues at University of California, April 2012. California’s Economic Payoff: Investing in College Access and Completion. The Campaign for College Opportunity.

- Ibid

- Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982)

- Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina and Chad Sparber, September 2012. In-state Tuition for Undocumented Immigrants and Its Impact on College Enrollment, Tuition Costs, Student Financial Aid and Indebtedness. Institute for the Study of Labor, Discussion Paper No. 6857

Justice Circle

Justice Circle