As one of 14 states left with a coverage gap, North Carolina is home to far too many people earning too little to afford health insurance but unable to qualify for Medicaid.1 While Medicaid provides coverage for some people with disabilities in our state, many North Carolinians living with disabilities, chronic illnesses, and other complex medical conditions fall through the cracks of the current system. Closing the coverage gap would allow these uninsured North Carolinians to qualify for coverage based on their low incomes, enabling them to access regular care and treatment for their conditions without fear of bankruptcy or deteriorating health.

N.C. Medicaid currently leaves out many people with disabilities, chronic illnesses, and complex medical needs who have low incomes

Contrary to popular belief, people living with disabilities in poverty are not automatically eligible for public health insurance coverage. While both programs offer coverage to some people with disabilities, Medicaid and Medicare exclude many people with disabilities and serious medical conditions.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines a disability broadly as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.”2 However, the Social Security Act (SSA) uses a narrower interpretation to define someone as having a disability based on “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment or combination of impairments that is expected to result in death or which has lasted or is expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”3 This restrictive definition was originally developed to design eligibility not for medical coverage but for Supplemental Security Income, a program designed to provide “income support when an individual’s ability to work is significantly impaired, rather than when broad criteria concerning functional or health status are met.”4

LIFE IN THE COVERAGE GAP: Struggling to manage chronic conditions without health insurance

A long-time truck driver, Diane lost her job a er being diagnosed with diabetes. Uninsured and in the coverage gap, she could not afford the medications needed to manage her disease. As a result, she developed neuropathy and now lives with chronic pain that makes it difficult for her to find work.

“I’ve always worked, I want to work. I don’t feel like I can because I hurt so much all the time but it would make me so happy to get better and go back to work.”

Despite her conditions, Diane was denied Medicaid because she was not deemed disabled and she does not have dependent children. She has since had catastrophic health problems, including several strokes, heart attacks, and three open-heart surgeries that have left her saddled with medical debt.

“If I did get the help I needed, I would be able to get the medicine I need to keep my sugar under control, my cholesterol under control, help me with the pain I’m going through, and even be able to afford decent food because I can’t afford but one or the other.”

This narrow definition of disability, used by North Carolina Medicaid,5 therefore excludes many North Carolinians with ADA-defined disabilities, as well as people with a wide range of chronic and complex medical conditions. As a result, people with physical disabilities, mental illnesses, substance use disorders, cognitive disabilities, chronic illnesses, life-threatening diseases, and other complex diagnoses o en find themselves in the coverage gap. Defining an “able body” this way has let too many people fall through the cracks, leaving them vulnerable to compromise by their conditions and lack of access to care.

However, even those North Carolinians who do meet the strict SSA definitions of disabled or blind must clear other hurdles to qualify for Medicaid: they must have both below-poverty income earnings and minimal assets, as low as $2,000 for an individual.6 As such, even otherwise eligible North Carolinians with disabilities living in poverty with modest savings may not qualify for N.C. Medicaid.7

Closing North Carolina’s coverage gap would let all nonelderly adults with low incomes who have disabilities, complex medical needs, and chronic illnesses access affordable health coverage, which would allow them to receive regular care and treatment for their conditions while protecting against financial ruin.

North Carolinians with disabilities, chronic conditions, and complex medical needs fall into the coverage gap

North Carolinians with disabilities, chronic conditions, and complex medical needs fall into the coverage gap

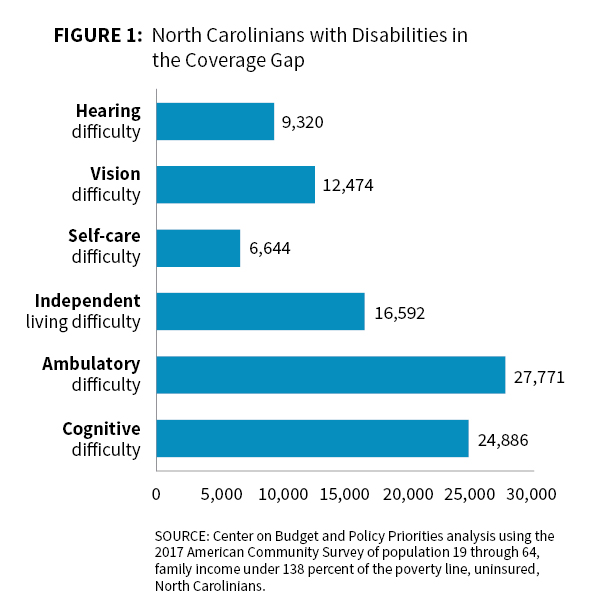

Some opponents of closing the coverage gap have claimed that it would benefit healthy, able-bodied adults. However, nearly 1 in 7 people in the coverage gap has a disability.8 Census data show that North Carolinians living with both cognitive disabilities and physical disabilities, such as difficulties with hearing, seeing, and walking, fall into the coverage gap. Thousands have trouble bathing or dressing on their own, and others have difficulty with independent living, such as problems doing errands alone due to physical, mental, or emotional problems.9 Over 54,000 North Carolinians in the coverage gap have at least one of these disability types, but 46 percent of them report experiencing more than one disability.10

NC can both close the coverage gap and support home- and community-based services for people with disabilities on the Innovations Waiver waiting list

There are no waiting lists for Medicaid coverage for eligible enrollees. However, some have alleged that closing the coverage gap will somehow disadvantage people with disabilities, and others have implied that closing the gap would harm people on the waiting list for the Innovations Waiver, a program to provide home- and community- based services (HCBS) for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD), most of whom currently have Medicaid coverage.

As fact checkers and researchers have previously found, there is no correlation whatsoever between HCBS waiting lists and whether a state closes the coverage gap.11,12 fact, of the 13 states without a HCBS waiting list in 2016, 10 of them were states that closed their coverage gap.13

North Carolina can both close its coverage gap and add waiver slots to support more people with I/DD in need of HCBS. In fact, because the federal government provides a stable 90 percent financial match for closing the coverage gap, doing so will produce state budget savings14 — savings which lawmakers could use to fund new waiver slots for the Innovations Waiver, among other purposes.

Many other North Carolinians in the coverage gap have chronic conditions and complex medical needs. Roughly 150,000 uninsured North Carolinians who have substance use disorders and/or mental illness could gain coverage if the state closes the gap,15 which would allow them to afford care and treatment. Based on the experience of other states, closing North Carolina’s coverage gap could result in 2,197 fewer uninsured opioid-related hospitalizations each year.16

One estimate suggests closing the coverage gap would result in 641 new cancer diagnoses a year, including 291 new early-stage cancer diagnoses.17 Like with other illnesses, early cancer detection significantly improves success rates for treatment.

LIFE IN THE COVERAGE GAP: Delaying health care until it is too late

Margie’s brother-in-law Jeff was living in the coverage gap, unable to afford a private plan with his earnings as a part-time cook at a nursing home. He was hurting, but “he couldn’t afford to go to the doctor,” Margie recalls. “He finally had so much pain, he went to the ER and was diagnosed with Stage IV kidney cancer, and didn’t last long after that.”

Had he had coverage, Jeff could have been able to seek medical attention before his symptoms worsened and his disease reached an advanced stage.

People with disabilities and complex medical needs are benefitting in states that have closed their coverage gaps

Coverage gains among people with disabilities and chronic conditions

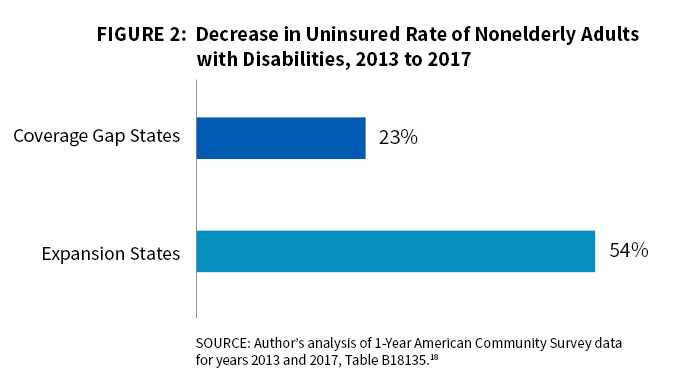

Since 2013, the year before the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansions were implemented, the uninsured rate among nonelderly adults with disabilities has fallen from 17 to 10 percent nationwide. However, coverage gap states lag behind expansion states in making such progress. The uninsured rate for nonelderly adults with disabilities in coverage gap states fell from 19 to 15 percent on average, while states that closed their coverage gap have seen uninsured rates among disabled adults fall from 16 to 6 percent.18

Specific results from states that closed their coverage gaps demonstrate that people with disabilities benefit from closing the gap. For example, among enrollees who gained coverage a er Michigan closed the gap, 23 and 20 percent had functional impairments related to a physical disability or a mental disability, respectively.19

Increased access to and use of health care services

Increased access to and use of health care services

Closing the coverage gap has improved access to and utilization of health care services, particularly among people with chronic conditions. Studies have shown that closing the gap has been associated with lower uninsured rates among cancer patients;20 improved access to cancer surgery;21 reduced mortality among dialysis patients;22 increased diagnoses of diabetes and high cholesterol;23 increases in prescriptions for diabetes medications24 and cardiovascular drugs;25 increases in prescriptions for and Medicaid spending on medications to treat opioid use disorder and opioid overdose;26 higher use of chronic disease management;27 and substantially improved mental health among patients with chronic conditions,28 among others.29

Employment boosts for people with disabilities

Closing the coverage gap also promotes employment for people with disabilities. A recent study30 found that people with disabilities are working at higher rates and that fewer report not working because of disability in states that closed the coverage gap. Closing the coverage gap increases the income eligibility threshold for Medicaid and does not impose asset limits, freeing up people with disabilities to work more without fear of losing their health care.

Footnotes

- The term coverage gap used here refers to currently uninsured adults who would be eligible for Medicaid under 42 U.S. Code § 1396a(a)(10) (A)(i)(VIII).

- 42 U.S. Code § 12102(1).

- “MA-2525 Disability.” Aged, Blind and Disabled Medicaid Manual. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Medical Assistance, Medicaid Eligibility Unit. https://www2.ncdhhs.gov/info/olm/manuals/dma/abd/man/MA2525.pdf

- “People with Disabilities.” Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/people-with-disabilities/. Accessed on May 26, 2019.

- “MA-2525 Disability.” Aged, Blind and Disabled Medicaid Manual. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Medical Assistance, Medicaid Eligibility Unit. https://www2.ncdhhs.gov/info/olm/manuals/dma/abd/man/MA2525.pdf

- “Basic Medicaid Eligibility.” North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Revised April 1, 2019. https://files.nc.gov/ncdma/ documents/files/Basic-Medicaid-Eligibility-Chart-2019.pdf.

- As allowed by the Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act (TWWIIA) of 1999, North Carolina also operates the Health Coverage for Workers with Disabilities (HCWD) program, which extends Medicaid eligibility to some people with qualifying disabilities whose incomes and/or assets exceed the eligibility limits for the Medicaid Aid to the Disabled (MAD) program if they meet other eligibility requirements. In addition to program rules requiring the individual with a disability to be employed, which excludes participation by people with disabilities not in the labor force whose household income or assets exceed the eligibility thresholds due to a family member’s income(s), there are many barriers to participation in the program by people with disabilities recognized by Social Security’s narrow definition. Some of these barriers include: lack of awareness and full understanding of the program’s availability, rules, and requirements by both the public as well as by the social services workforce; the lack of counseling options available to help individuals understand the requirements and implications of increased employment/substantial gainful activity on their eligibility for other public benefits; and the generally complicated program rules and requirements of the program, among others. See more on the HCWD program at: “MA-2180 Health Coverage for Workers with Disabilities.” Aged, Blind and Disabled Medicaid Manual. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Medical Assistance, Medicaid Eligibility Unit. https://www2.ncdhhs.gov/info/olm/manuals/dma/abd/man/MA2180.PDF

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis using the 2017 American Community Survey of population 19 through 64, family income under 138 percent of the poverty line, uninsured, North Carolinians.

- Explanations of disability types available here: “How Disability Data are Collected from The American Community Survey.” United States Census Bureau. Last Updated October 17, 2017. https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-collection-acs.html

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis using the 2017 American Community Survey of population 19 through 64, family income under 138 percent of the poverty line, uninsured, North Carolinians.

- Musumeci M. “Data Note: Data Do Not Support Relationship Between Medicaid Expansion Status and Home and Community-Based Services Waiver Waiting Lists.” March 22, 2018. https://www.k .org/medicaid/issue-brief/data-note-data-do-not-support-relationship-medicaid- expansion-hcbs-waiver-waiting-lists/

- Lee, MYH. “Did the Obamacare Medicaid expansion force people onto wait lists?” Washington Post. March 24, 2017. https://www. washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2017/03/24/did-the-obamacare-medicaid-expansion-force-people-onto- waitlists/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.2fb0fb0e1060

- Musumeci M. “Data Note: Data Do Not Support Relationship Between Medicaid Expansion Status and Home and Community-Based Services Waiver Waiting Lists.” March 22, 2018. https://www.k .org/medicaid/issue-brief/data-note-data-do-not-support-relationship-medicaid- expansion-hcbs-waiver-waiting-lists/

- Khachaturyan, S. “North Carolina Can’t A ord a Coverage Gap.” North Carolina Justice Center, Budget & Tax Center. May 23, 2019. https:// www.ncjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/FACT-SHEET_Financing-Medicaid-expansion.pdf

- Dey J, Roseno E, West K, Ali MM, Lynch S, McClellan S, Mutter R, Patton L, Teich J, Woodward A. “Benefits of Medicaid Expansion for Behavioral Health.” US Department of Health and Human Services, O ice of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. March 28, 2016. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/190506/BHMedicaidExpansion.pdf; See also: North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. “Strategic Plan for Improvement of Behavioral Health Services.” Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. https://files.nc.gov/ncdma/documents/Reports/Legislative_Reports/SL2016-94-Sec12F-10-and-SL2017-57- Sect11F-6_2018_01.pdf

- West, R. “Expanding Medicaid in All States Would Save 14,000 Lives Per Year.” Center for American Progress. October 24, 2018. https://www. americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/reports/2018/10/24/459676/expanding-medicaid-states-save-14000-lives-per-year/

- West, R. “Expanding Medicaid in All States Would Save 14,000 Lives Per Year.” Center for American Progress. October 24, 2018. https://www. americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/reports/2018/10/24/459676/expanding-medicaid-states-save-14000-lives-per-year/

- Author’s analysis of 1-Year American Community Survey data for years 2013 and 2017, Table B18135.

- “Many Medicaid Enrollees Have a Disability – Especially Those Not Working.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/

many-medicaid-expansion-enrollees-have-a-disability-especially-those-not-working - Han X, Yabro KR, Ward E, Brawley OW, Jemal A.. “Comparison of Insurance Status and Diagnosis Stage Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cancer Before vs A er Implementation of the Patient Protection and A ordable Care Act.” JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1713-1720. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3467. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/article-abstract/2697226

- Eguia E, Cobb AN, Kothari AN, Molefe A, Afshar M, Aranha GV, Kuo PC. “Impact of the A ordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid Expansion on Cancer Admissions and Surgeries.” Ann Surg. 2018 Oct;268(4):584-590. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002952. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/30004928

- Swaminathan S, Sommers BD, Thorsness R; Mehrotra R, Lee Y, Trivedi AN. “Association of Medicaid Expansion With 1-Year Mortality Among Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease.” JAMA. 2018;320(21):2242-2250. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.16504 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/ jama/article-abstract/2710505?resultClick=1

- Wherry LR, Miller S. Early Coverage, Access, Utilization, and Health Effects Associated With the A ordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions: A Quasi-experimental Study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:795–803. doi: 10.7326/M15-2234. https://annals.org/aim/article-abstract/2513980/ early-coverage-access-utilization-health-e ects-associated-a ordable-care-act

- Myerson R, Lu T, Tonnu-Mihara I, Huang ES. “Medicaid Eligibility Expansions May Address Gaps In Access To Diabetes Medications.” Health A airs. August 2018. https://www.healtha airs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hltha .2018.0154

- Ghosh A, Simon K, Sommers BD. “The E ect of State Medicaid Expansions on Prescription Drug Use: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act.” NBER Working Paper No. 23044. January 2017. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23044

- Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S. “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review.” Kaiser Family Foundation. March 28, 2018. https://www.k .org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-e ects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca- updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/

- Sommers BD, Gawande AA, Baicker K. “Health Insurance Coverage and Health — What the Recent Evidence Tells Us.” N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 10;377(6):586-593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1706645. Epub 2017 Jun 21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28636831/

- Winkelman TNA, Chang VW. “Medicaid Expansion, Mental Health, and Access to Care among Childless Adults with and without Chronic Conditions.” J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Mar;33(3):376-383. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4217-5. Epub 2017 Nov 27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/29181792/

- Read more in the following literature reviews: Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S. “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review.” Kaiser Family Foundation. March 28, 2018. https://www.k .org/medicaid/issue-brief/the- e ects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/; “Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act: Changes in Coverage and Access.” Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/ changes-in-coverage-and-access/

- Hall JP, Shartzer A, Kurth NK, Thomas KC. “Medicaid Expansion as an Employment Incentive Program for People With Disabilities.” Am J Public Health. 2018 Sep;108(9):1235-1237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304536. Epub 2018 Jul 19. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/30024794

Justice Circle

Justice Circle